SustainaWeekly - How large and effective are Dutch energy transition subsidies?

The Netherlands is the second European country with the largest number of subsidies towards renewable energy. We start this week’s SustainaWeekly by digging into how large these subsidies are, and evaluate their effectiveness so far. We argue that despite the large number of subsidies, some challenges around increasing renewable energy investment remain. Governments also play a key role to ensure that subsidies are rolled out as effective as possible. In our next note, we look at the recently published piece of the ECB on biodiversity risks. Finally, we then move to explore the carbon capture technology.

The role and effectiveness of Dutch transition subsidies

The energy transition is essential in achieving emission reductions and climate targets in time

In this note we zoom into subsidies for renewable energy production and climate transition (SCE/SDE) offered by the Dutch government to enhance clean projects matching the transition agenda

Due to challenges around cost of financing, labour market tightness, nitrogen limits, and the electricity grid, we emphasize the need for a dynamic, timely, and proactive subsidy scheme

Coordinating the different components of the transition process is essential for keeping the scheme up to date to reflect the impacts of any emerging obstacles

Subsidy schemes for clean technologies should align with other climate policies, such as carbon pricing, to achieve a timely, orderly, and efficient transition

The energy transition is essential in achieving emission reductions and climate targets in time. However, even with the readiness of the needed technologies, the deployment is still not up to speed. A main challenge comes from reluctance, which is driven by the high associated costs and lower competitiveness of low carbon technologies in comparison to the fossil fuel abased alternatives. Access to finance is another obstacle for low carbon investments as these investments are capital intensive, long-term, and usually associated with uncertainties, increasing their risk profile that does not match the risk appetite of most private investors. Furthermore, for some transition needed technologies, having a carbon price is not enough and leaving the transition to market dynamics will take too much time. Subsidies, such as CAPEX and OPEX subsidies, are one way to complement carbon pricing to enhance the adoption of different clean technologies. In this note, we zoom into subsidies for renewable energy production and climate transition (SCE/SDE) offered by the Dutch government to enhance clean projects matching the transition agenda. We start by reviewing the background of these subsidies and their targets. We move afterwards to their status, effectiveness, and practical implications. Finally, we conclude with suggestions and recommendations for more effective schemes.

An overview of the Dutch low carbon and transition subsidy schemes

In this section, we give an overview the most prominent Dutch subsidy schemes that aim to incentivize investments in low carbon and transition needed technologies.

Money reserved by the government for transition subsidy schemes is mainly financed by the revenues from the auctioning of emission allowances under European Union Emission Trading Scheme (EU-ETS). Another part of the financing for these projects originates from the Dutch cabinet’s plan to spend more money on reaching climate goals (). There are different subsidy schemes by the Dutch government. Namely: (i) Subsidy Demonstration Energy Innovation (DEI+), which is targeted towards projects at a pilot or demonstration phase with a focus on one of seven themes 1); (ii) the Subsidy scheme for Cooperative Energy Generation (SCE), which aims to stimulate the generation of renewable energy from solar, wind, or hydro sources by energy cooperatives and homeowners' associations; and (iii) the Simulation of sustainable energy production and climate transition (SDE++), which targets renewable energy generation projects or the implementation of CO2 reduction technologies (CO2 storage/low-CO2 production ()). The SCE scheme was launched in April 2021 with EUR 92 million available for the first round. It is an OPEX subsidy that guarantees the profitability of the installation through its lifetime. With regards to the SDE++, it is also an OPEX subsidy but aims to subsidize the difference between the market value of produced energy and the cost of renewable energy production, guaranteeing the profitability of such project. Other subsidy related developments include a new €28.1 billion Climate Package for reducing CO2 emissions (). This package is mainly targeted towards onshore and offshore green hydrogen production, storage, imports, and a pipeline network in the North Sea.

International subsidy schemes

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), global investments in energy transition technologies in 2022, including energy efficiency, reached USD 1.3 trillion. It is an astronomical amount and even proved to be a new record in the level of investments. At first sight, this is very encouraging, of course, but unfortunately much more is needed than this. IRENA thinks the global energy transition will require another USD 150 trillion investment in a variety of low-carbon technologies between 2023 and 2050. This would mean an annual investment of EUR 6.8 trillion globally a year from now. This means that we still have a long way to go.

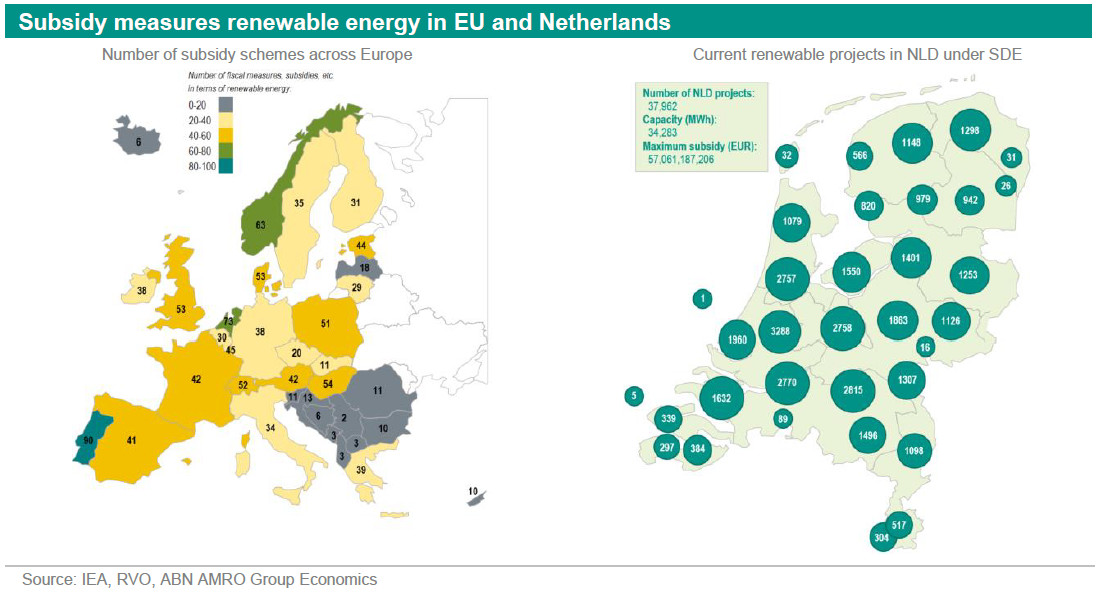

Below we show how many renewable subsidy opportunities there are currently per country in Europe. Leading with a number of 90 renewable energy subsidy schemes in Europe is Portugal. The Netherlands is second in this perspective with 73 subsidy schemes, closely followed by Norway. From the graph it also becomes clear that there are plenty of options spread across Europe to encourage renewable energy financing.

In the Netherlands, the renewable energy subsidy scheme (SDE++) is very popular. This is evident not only from the strong growth in the number of projects spread across the Netherlands, but also from the strong growth in the number of applications to the SDE++ subsidy. This shows that subsidy schemes for climate financing from the government will continue to play an important role in the coming years. Not only to boost capacity and installed capacity, but also to serve as bridging the financing gap for companies with less financial capacities.

What have the subsidies generated so far and what is still in the pipeline?

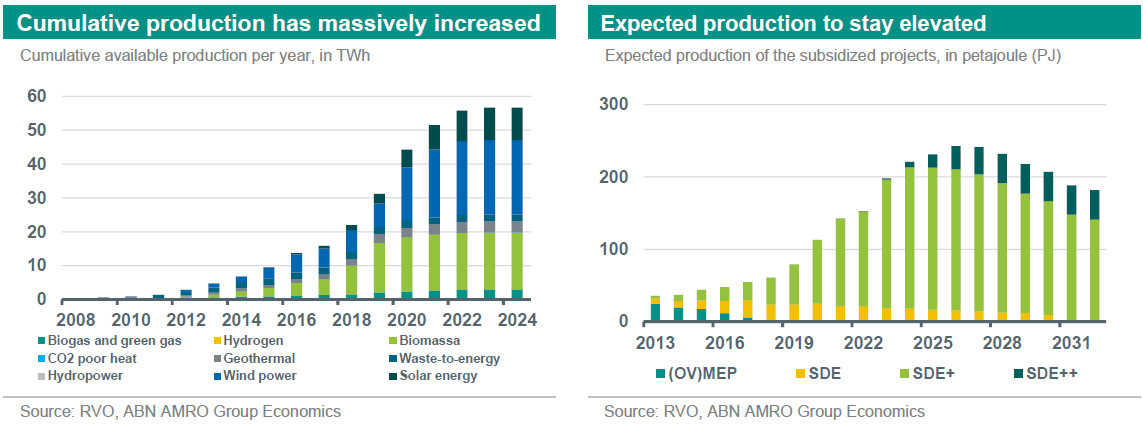

In this section we highlight the progress of the SCE and SDE++. We do this by using data provided by the RVO (the Netherlands Enterprise Agency), which allows for illustrating the power these projects have generated so far, and what is still in the pipeline.

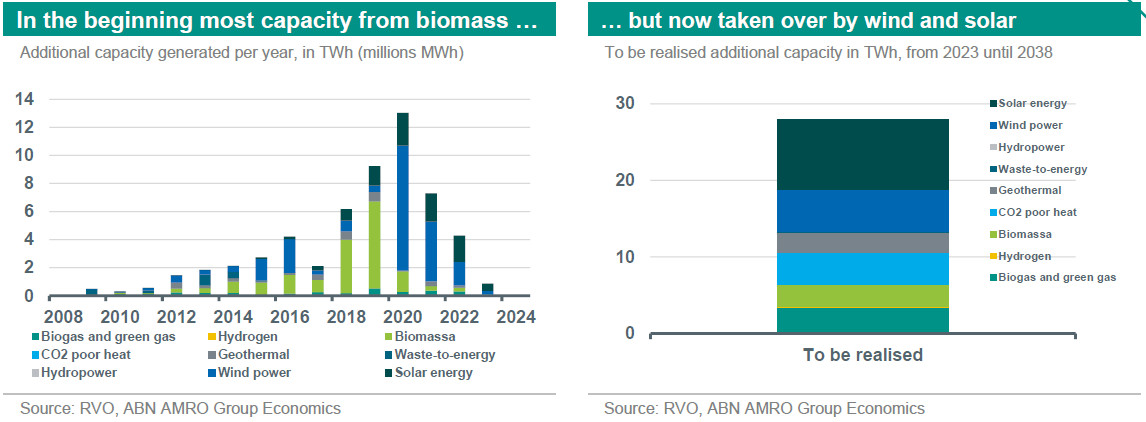

Together with solar power, wind is also largest source from which additional capacity will still be realized. This is visualized in the two graphs on the next page. Several factors could have played a role in the switch from biomass to solar and wind energy when granting the subsidy. This could be sparked by the European Green Deal and the ‘Fit for 55’ package, but also the higher energy price caused by the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and prioritizing energy security more generally. Additionally, a shift in policy focus took place as since the start of the SDE++ subsidy, the attention has shifted to CO2-reduction rather than energy production ().

There are still many projects that have recently received access to the subsidy scheme, and they still are to be started. The maximum period with which the projects are realized is 15 years, meaning that there is still about 28 TWh of yearly generated capacity in the pipeline until 2038. The right-hand figure below shows the expected production of subsidized projects until 2038.

Challenges to effective subsidy schemes

Making substantial investments in clean technology projects is becoming more and more challenging even with the presence of subsidy schemes. A recent firm level survey by the ECB () reports that three quarters of firms have plans to invest in clean technology projects. However, the cost of financing is an issue. Half of the surveyed firms identified too high financing costs – as a result of the tightening of monetary policy by central banks leading to high interest rates and tightening financing conditions – as posing a significant obstacle to invest.

The success of the subsidy schemes depends in large part on the absence of any obstacles that hinder the transition process. That is, the problem of insufficient low carbon investments can also be driven by bottlenecks, such as unclarity of future regulations, long permitting times, and limits to infrastructural capacity. These form constraints and challenges facing the transition and adversely undermine any subsidy scheme in place. For the Netherlands, there are mainly two constraints in particular: labour market tightness and nitrogen limits. In the considerable sustainability efforts that need to be made, professionals for the energy transition are essential but unfortunately hard to find. The second constraint comes from nitrogen limits, as it delays the expansion of electricity channels but is essential in laying the foundation for the transition. The cap on nitrogen pollution thus affects the construction of electricity networks, but also construction and infrastructure generally ().

Furthermore, a disadvantage of the subsidy schemes is that they have a large administrative burden. The subsidy grant depends on energy prices and is determined in a backward looking way. This increases the administration that comes with the projects and finances (), which also poses limits on possible solutions or extensions.

Conclusions and recommendations for successful subsidy schemes

We conclude that the current Dutch subsidy schemes are appropriate to stimulate and incentivize corresponding clean investments. Also, these subsidy schemes prove to be very popular among SMEs. However, considering the above-mentioned challenges, we emphasise the need for a dynamic, timely, and proactive subsidy scheme that considers the developments in the market environment to avoid delays or fall backs in the transition process. For example, last month offshore auction in the UK did not receive any bids mainly because the subsidy strike price did not take into consideration the increase in inflationary pressures on the industry-wide production cost. In addition, coordinating the different components of the transition process is essential for keeping the scheme up to date to reflect the impacts of any emerging obstacles. Finally, subsidy schemes for clean technologies should be aligned with other climate policies, such as carbon pricing, to achieve a timely, orderly, and efficient transition.

This note is based on a more extended publication which can be found here.

1) The themes are: circular economy; energy efficiency; flexibility of energy systems; renewable energy; Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS); local infrastructure; any other measure that reduces CO2 emissions in the built environment, industries or power generation; Houses, buildings, and blocks that do not use gas