One of the hottest topics of the decade: biodiversity

There are two types of risks associated with biodiversity. Physical risks stem from the loss of biodiversity and transition risks stem from regulations/policies introduced by regulators to mitigate biodiversity loss risks. Several central banks have calculated their national financial institutions exposure to biodiversity risks. Results are discouraging, but regulators have already a few regulations in place to try to mitigate the loss.

Biodiversity stands for biological diversity. The loss of biodiversity translates into the loss of services provided by ecosystems to the real economy

There are two types of risks associated with biodiversity: physical and transitions risks

Physical risks stem from the loss of biodiversity (e.g. disappearance of animal pollinators), and transition risks stem from regulations/policies introduced by regulators to mitigate biodiversity loss risks (e.g. the introduction of a tax on fertilizers)

The ENCORE database provides scores for each sector and sub-sector on their exposure to biodiversity risks

De Nederlandsche Bank, the Banque de France and the Bank of England used the above database to calculate their national financial institutions exposure to biodiversity risks

Results are discouraging, but regulators have already a few regulations in place to mitigate biodiversity loss risks

Life as we know it might well be at risk. Approximately one million species are currently on the brink of extinction, and, according to the Organization for Economic, Co-operation and Development (OECD), the world already lost an estimated EUR 3.5 - 18.5 trillion per year in ecosystem services from 1997 to 2011 owing to land-cover change. But what does this mean for biodiversity? Or for firms and individuals that highly depend on the viability and longevity of biodiversity?

That is what national central banks, like the Bank of England (BoE), the Banque de France, and De Nederlandsche Bank, have been trying to answer in recent years. More recently, the European Central Bank (ECB) also published a written statement () revealing that it would publish a report in 2023 showing how much the euro area economy and financial sector are exposed to risks related to ecosystem services. This report is yet to be published.

This Sustainaweekly is only the first of a few pieces about the topic that we will publish through to the end of this year. In this first piece, we provide a brief description of what biodiversity is, what are biodiversity-related risks, how these risks are measured, and what regulations / policies are currently in place. In our soon to-be published ESG Outlook for 2024, we will calculate each sector’s exposure to biodiversity risks, and assess the exposure of 17 European banks considering their loan book and each sector’s biodiversity score. Moreover, a final piece will follow focusing on investors, and what is the perception of investors regarding biodiversity.

But first, what is biodiversity?

Biodiversity stands for biological diversity, and captures the variety and variability of life on Earth. Furthermore, ecosystems – which entail all the living things in a particular area as well as the non-living things – are built upon the basis of biodiversity. As such, the loss of biodiversity in a certain ecosystem translates into a loss of the services that ecosystems provide to the real economy. There are four different types of ecosystem services :

Provisioning services of tangible products, such as food, timber and cotton;

Regulating services, such as animal pollination, air and water treatment, and soil fertility;

Cultural services, which are ecosystems contributions to sectors like education, recreation, and tourism;

Supporting services, such as the nutrient cycle, soil conservation and habitat creation.

The diversity of species is of crucial importance for ensuring that ecosystems are stable and function well over the longer term. Such that, the loss of biodiversity would translate into economic consequences for a company that can be severe, and hard to predict.

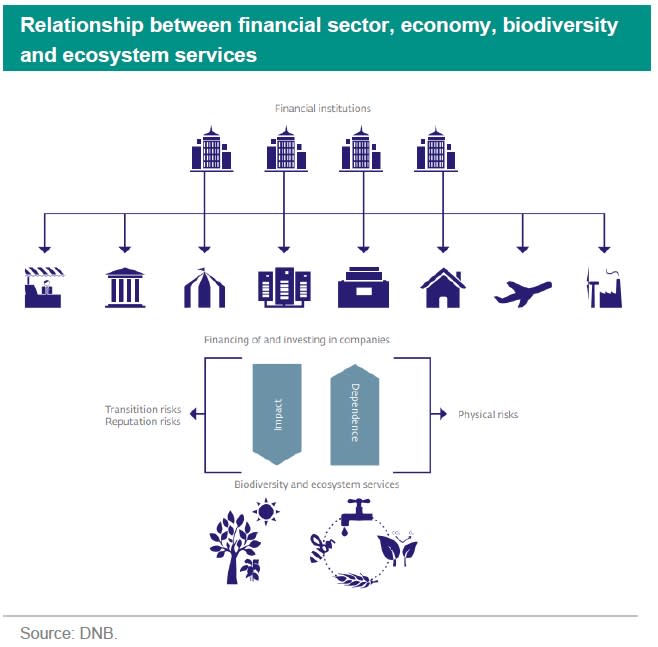

Despite the complexity of calculating a company’s exposure to biodiversity, regulators have been developing tools and methodologies in order to evaluate the exposure of firms to biodiversity loss, and, ultimately, to quantify financial institutions’ exposure to these companies. Below, we plot a graph depicting the relationship between ecosystem services, non-financial institutions, and financial institutions.

What are biodiversity-related risks?

The first challenge is to define the risks that companies are facing. Risks can either be physical, stemming from the loss of biodiversity, like the extinction of bees, and ultimately in the disappearance of animal pollination. Or can be transition risks, stemming from regulations adopted by governments to avoid biodiversity loss, like the introduction of taxes on fertilizers.

Furthermore, these risks will have different consequences throughout the value chain. For instance, the loss of crop production can have a negative impact on the profitability of primary producers, but it will also affect raw material prices that food processors face. In the above-mentioned methodologies, regulators only accounted for first-order dependencies, given how complex it would be to capture all ecosystem services involved in a company’s operations. As such, the risks set out are most likely an underestimation.

How to quantify physical and transition risks?

The physical risks related to biodiversity are captured by the dependence of a company on a certain ecosystem service (i.e. a business which is highly dependent on ecosystem services is more likely to be directly affected by a physical shock). Regarding transition risks, these are captured by how much a company impacts the ecosystem, i.e. a business with a significant negative impact on biodiversity has a higher chance of being affected by biodiversity policies (transition shock) than a business with a low impact.

But how could a financial institution start to map the dependence and impact of the companies in its loan book? The provides these dependence and impact scores by sector and sub-industry regarding 21 ecosystem services. The score ranges between very high materiality to very low materiality. When provided with the scores, one is able to calculate the dependence and impact a company has on biodiversity based on the number of products and the location of the company’s production assets. Finally, with the help of balance sheet data from financial institutions, it is possible to determine the extent of lending to, and investment in, sectors with products that are dependent on a certain ecosystem or that extensively impact a certain ecosystem.

Results from central banks

According to Banque de France, considering Scope 1 dependencies to ecosystem services, i.e. the dependencies of direct operations, 42% of the value of loans and investments held by French financial institutions comes from borrowers that are highly or very highly dependent on at least one ecosystem service. According to DNB’s report, this number is 36% for Dutch financial institutions. Both reports indicate that the highest dependence is on the ecosystems that provide groundwater and surface water.

The Bank of England has also conducted a similar analysis considering the UK economy, and they found that over half (52%) of UK GDP and nearly three quarters (72%) of the stock of UK lending exhibits dependence on ecosystem services – levels that suggest elevated vulnerabilities.

In terms of transition risk, the biodiversity footprint of Dutch financial institutions is comparable with the loss of over 58.000km2 of pristine nature. This is an area more than 1.7 times the land surface of the Netherlands. In the case of France, the accumulated terrestrial biodiversity footprint of the French financial system is comparable to the loss of at least 130.000km2 of pristine nature.

What are regulators doing?

Even tough the numbers are discouraging, regulators worldwide are aware of the urgency of the topic, and have adopted policies / regulations to mitigate biodiversity loss risks. According to the OECD PINE database (see ), the most common ones are taxes on pesticides, fertilizers, forest products and timber harvests. Currently, there are 234 biodiversity-relevant taxes in place across 62 OECD countries, which generate USD 7.7bn in revenue every year. Even though it is already a considerable amount, it only represents 0.92% of all environmentally-related tax revenue.

Furthermore, there are also biodiversity-related tradable permits. The latter include individual transferable quotas (ITQs) for fisheries, tradable development rights, and tradable hunting rights. These quotas limit the total amount of a natural resource that can be exploited. Currently, 39 schemes are in place across 26 OECD countries.

Moreover, biodiversity-related subsidies are also another form of regulation in place. Examples of these subsidies include environmentally-motivated subsidies that target forest management and reforestation, organic or environmentally-friendly agriculture, pesticide free cultivation, and land conservation. There are currently 163 environmentally-motivated subsidies across 28 countries, as reported in the PINE database.

Finally, the European Commission (EC) also published its , in which it pledges that by 2030, at least 30% of the land and 30% of the sea should by protected in the EU. This is a minimum of an extra 4% for land and 19% for sea areas as compared to 2020. Moreover, it pledged to reverse the decline of pollinators, to reduce the use of pesticides by at least 50%, to have at least 25% of agricultural land under organic farming management, and to plant three billion new trees in the EU, in full respect of ecological principles.

This article is part of the SustainaWeekly of 23 October 2023