Global Monthly - Where are we with supply-side bottlenecks?

We are seeing early signs of the impact of the war in Ukraine on trade flows, and the constraint this is putting on industry. Alongside China lockdowns, bottlenecks look set to worsen in the near term. However, a general cooling in consumption will help to ease pressure on the supply-side. Risks to inflation continue to be to the upside. ECB worries over inflation expectations led us to bring forward our expectation for rate hikes, and we continue to expect the Fed to hike aggressively.

Bottlenecks will worsen in the near-term, but cooling consumption is helping

Notwithstanding the significant headwinds, the global economy has largely continued its post-pandemic recovery over the past month. April PMIs in Europe and the US signalled further solid growth in output, although manufacturing PMIs in the eurozone and UK clearly indicate that the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the accompanying rise in commodity prices is beginning to constrain growth. However, with significant room still for recovery post-pandemic, the services sector is exhibiting resilience, at least so far. We continue to expect that resilience to fade as the year progresses, as the significant hit to real incomes from high inflation restrains consumers’ ability to maintain the growth rates in consumption we have seen over the past few months. Already we are seeing signs of this in goods consumption, where the bulk of the inflation spike has been concentrated; retail sales volumes fell in the US and the UK, and we could well see similar moves in many eurozone countries (the forward-looking component of the services PMI gives an early signal of this). This will be a welcome development for the supply-side, which as we discuss in this month’s Global View, is facing renewed headwinds from both the conflict in Ukraine, and lockdowns in China. Indeed, continued upside risks to inflation – still largely supply-side driven in the eurozone – have led us to bring forward our expectation for ECB rate hikes, and we expect monetary policy more broadly to continue to be tightened aggressively over the coming months.

Early signs of trade realignment, and increased supply disruptions in Europe

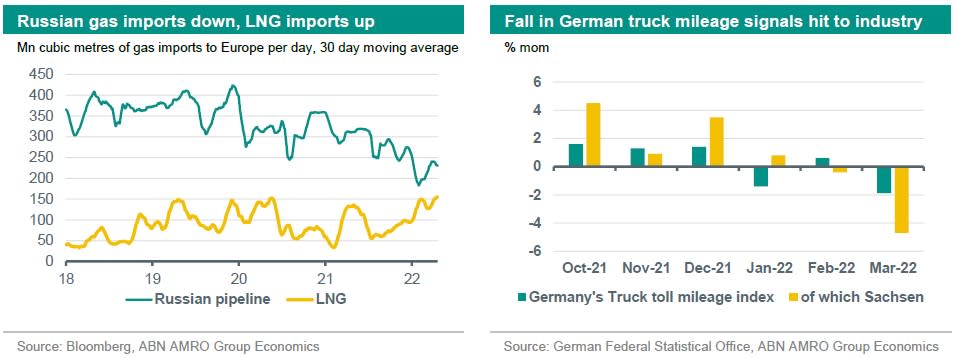

Following the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine, and the imposition of sweeping sanctions by western governments against Russian entities, we took the that we were at the beginnings of a structural realignment of trade flows that would have major short- and long-term macro-economic implications. Although it is still early days and data is scant, sanctions have already encouraged a measurable shift in some trade flows; in the year to date so far, Russian pipeline flows to Europe are around 30% below 2021 levels, while European LNG imports are around 60% higher. At the same time, numerous companies have ‘self-sanctioned’ on the expectation of future restrictions on trade with Russia. Germany – whose industry is highly dependent on Russian energy – has announced that it has already reduced its dependence on Russian coal from 50 to 25%, oil from 35 to 25%, and gas from 55 to 40%. Detailed trade data come with a significant lag, but in the coming months it is likely to show more broadly how the conflict and sanctions are affecting trade flows.

Meanwhile, governments have followed up sanctions with the setting of explicit goals to reduce dependence on Russian energy. For instance, in early March, the EU announced the goal to reduce Russian gas imports by 2/3 in one year. Germany’s goal is to all but wean itself off Russian gas by mid-2024 and, according to Vice Chancellor Habeck, become ‘virtually independent’ of Russian oil by December. These goals seek to strike a balance between doing so as quickly as possible, and minimising economic disruption. In our view, some of the goals (especially the EU’s plan to reduce Russian gas imports by 2/3 in one year) are ambitious to the point of being . However, the direction of travel is clear, and we continue to take the view that regardless of how the conflict evolves, trade flows will see a structural realignment over the coming months and years. In the meantime, there is the continued risk of a more abrupt shift in trade flows if Europe imposes a full embargo on Russian energy imports, or if Russia cuts off energy supplies to Europe.

How disruptive has this realignment been for economies so far? Consistent with our base case, the bulk of disruption has been via the surge in energy and other commodity prices, rather than physical disruption to supplies. High frequency data and surveys suggest that there was a considerable negative impact from the jump in energy, food and other commodity prices. For instance, Germany’s Truck toll mileage index fell by 1.9% mom in March, after growing by 0.6% in February. There is a clear correlation between regional truck toll mileage and turnover in manufacturing, especially in regions with a strong industrial base. Indeed, the sharpest drop was registered in the industrial region Sachsen in the east of Germany (see figure above). Given this, we view the fall in truck mileage as an early indicator that elevated prices are weighing on production. This was corroborated by eurozone manufacturing PMIs this morning, which fell in March (see eurozone). In the Netherlands, we have noted a number of construction projects being halted, in part at least due to surging materials costs. Some energy-intensive sectors such as horticulture have also seen production halts, while companies in other sectors have gone bankrupt – though some of these companies already faced difficulties even before the recent price spikes.

The US is a relative bright spot, with some signs of easing in domestic bottlenecks

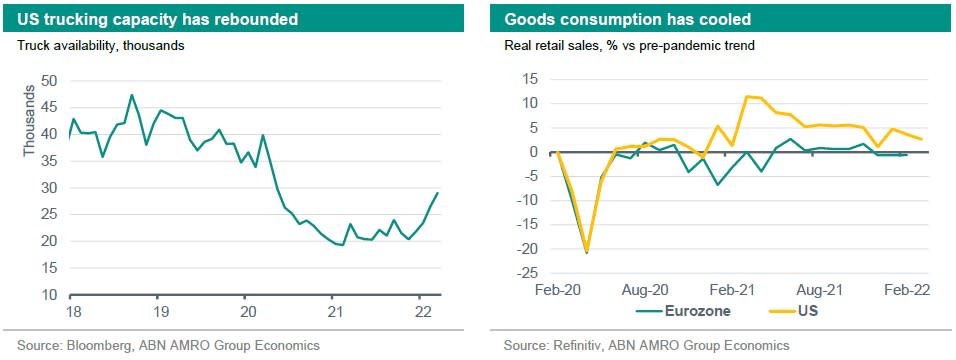

As we indicated in our March Global Monthly, Europe is being more heavily impacted by these price surges and supply-side disruptions than the US. While US consumers are also suffering a blow to their real incomes – mainly via the surge in gasoline prices (see US for more) – industry is more insulated from the effects given that the US is largely energy independent, with natural gas prices rising by a fraction of what we have seen in Europe. In some respects supply-side disruption has actually eased in the US. For instance, a major bottleneck for much of 2021 was a shortage of trucking capacity to meet the surge in goods demand. According to high frequency data from Truckstop.com, while there is still a shortfall in capacity compared to pre-pandemic levels, there has been a clear improvement in the year to date so far, with the number of trucks available up 25% on 2021 levels, albeit still around 30% below 2019 levels. According to Bloomberg, this improvement has been due to a flood of new entrants to the market, likely spurred by the jump in trucking rates.

At the same time, the cooling in demand suggested by the fall in real retail sales has seemingly had a knock-on effect on trucking demand, which is c.30% below 2021 levels. The easing in the trucking bottleneck has helped relieve congestion in ports; the number of ships waiting to unload for more than 9 days is down by around half compared to levels last October. To be clear, supply-side bottlenecks remain significant in the US, as is the risk of spillover effects from European supply-side disruptions and lockdowns in China, and for this reason inflationary pressure is expected to remain elevated over the coming months. However, on the domestic front at least, there are some tentative signs of an easing.

Chinese lockdowns have broadened as the country is struggling with Omicron…

In China, meanwhile, the spread of Omicron has driven a renewed tightening of mobility restrictions including lockdowns of major cities. Shanghai has become the epicentre of the outbreak, driving the bulk of the recent rise in cases. The Shanghai government implemented a lockdown in late March that was broadened and extended, with shortages of food and medicine adding to social discontent. Tech hub Shenzhen in Guangdong was another large city implementing a full one-week lockdown in late March. More broadly, among the 100 largest cities in China, eight of them - accounting for almost 9% of GDP - were in a full or partially residential lockdown by 20 April, and a wider group of cities accounting for a third of GDP were in some form of a non-residential lockdown. Many local authorities have proactively tightened restrictions even in regions/cities were cases remained quite low. This reflects the central government’s ongoing preference for a hawkish stance on covid-19 policy. In late 2021, China had tweaked its Covid-19 policy from a centralised ‘zero-cases approach’ to a decentralised ‘dynamic clearing’. However, the spread of Omicron has prevented this shift from being effective so far. The bar for the central leadership to fundamentally ease Covid-19 policies at short notice is high, with the CCP balancing between ongoing strict pandemic control and economic stability in the run-up to high-profile political events later this year. That also implies that policy makers will remain gradual and cautious with regard to reopenings.

…adding to supply bottlenecks and transport and production issues

The widening of lockdowns in March/April does not only exacerbate the pandemic-related drags to China’s economic growth (see China regional part), but also adds to disruptions in transport and production, with spillovers to global supply chains. A key issue are the problems in truck transport, caused by all kinds of city-specific restrictions. This contributes to delays in deliveries, shortages of supplies and port congestion, particularly around Shanghai. While there are reports of factories keeping staff at office overnight to ensure business continuity, supply bottlenecks within China have clearly intensified. The share of A-listed Chinese manufacturing companies that have reported covid-19 related disruptions has jumped to levels similar to the original outbreak in early 2020, although now with a broader regional spread. According to local reports, only one third of the around 650 Shanghai manufacturing firms that were ‘whitelisted’ to restart production is fully operational yet. Several tech leaders have warned for wider production stops if these disruptions linger. There is also evidence of foreign companies temporarily halting production in Shanghai or other cities, such as Tesla and Taiwanese iPhone producer Pegatron. On the macro level, developments in Chinese industrial (including car) production and the manufacturing PMIs are another illustration that the widening of lockdowns is affecting the supply side of the economy. Meanwhile, the government has recognised these issues as a top priority and is rolling out measures to ease supply bottlenecks and support production.

Global supply bottlenecks are intensifying for now, though there are also reasons for optimism

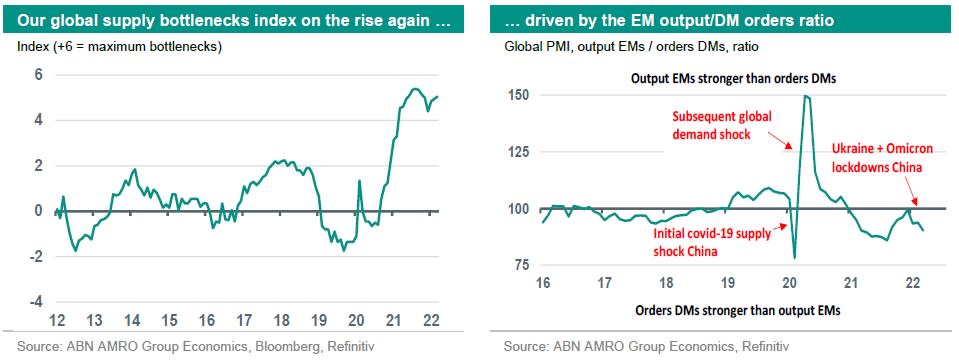

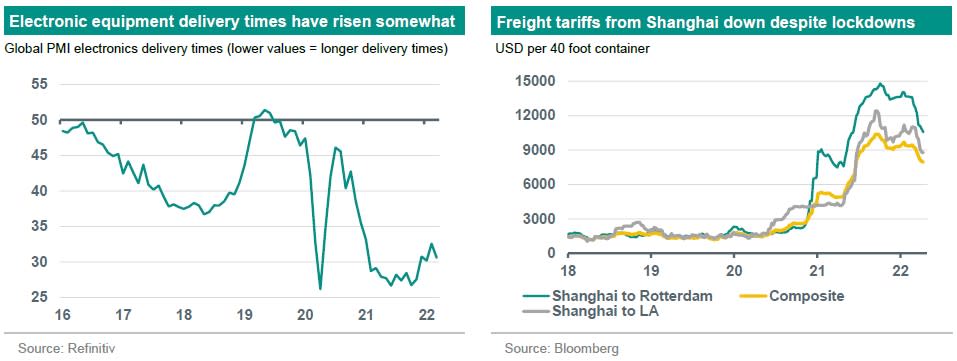

On balance, China’s lockdowns and the impact of sanctions against Russia on a range of commodity markets are adding to global supply bottlenecks, notwithstanding some other signs of improvements. Our global supply bottlenecks index has risen again in early 2022, pointing to rising bottlenecks overall. In the short term, there is a risk that these disturbances to global supply chains will not only intensify but will also last longer. For instance, delivery times for electronic equipment have risen again somewhat in March, after easing in late 2021. Next to the risk of prolonged lockdowns in China, there is still also the risk of a broader European embargo on Russian oil and gas which would amplify disturbances on the energy front.

Still, there are some reasons for optimism. First, there are the aforementioned signs of an easing in certain domestic bottlenecks, partly driven by cooling demand from even higher inflation which is helping to ease supply-demand imbalances. The recent increase in our global supply bottlenecks index is mainly driven by a fall in markets output relative to developed market demand. However, this ratio should start improving as pandemic disturbances in China fade. Already a few underlying components used in our index (e.g. container tariffs, Baltic Dry Index) point to an easing in some of these bottlenecks. Even shipping tariffs from Shanghai have continued falling in recent weeks (see chart), despite lockdowns and rising port congestion.