Euro Rates Strategist - The implications of the new EU fiscal rules

The EU finally managed to agree on a new set of fiscal rules in late 2023. The old fiscal benchmarks have remained, but the path to them will be less restrictive, enabling countries to adjust more gradually.

However, this will still represent a significant fiscal effort for the most indebted countries…

… which could lead to a recession and social tensions if implemented too fast

The strongest incentive for countries to adhere to the EU fiscal rules probably lies in the possible future activation of the ECB’s TPI instrument …

… as only countries that comply with the EU fiscal framework are eligible for asset purchases by the Eurosystem

Thus, this could have a significant impact on bond yields of countries that would fail to meet those rules

As such, we judge that the new fiscal rules combined with the EU and ECB conditionalities on their support programmes will incentivise countries to repair their public finances

Furthermore, if conducted and implemented thoroughly, we expect spreads to tighten significantly in the longer-term as risk premia shrink

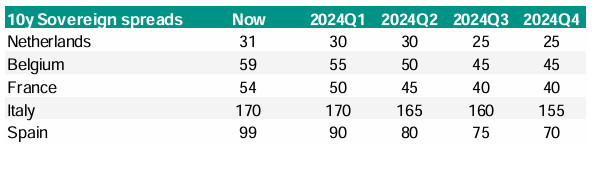

In the meantime, we expect country spreads to slightly tighten in 2024, as we expect the rate-cut cycle to be the dominant driver

Full report:

Introduction

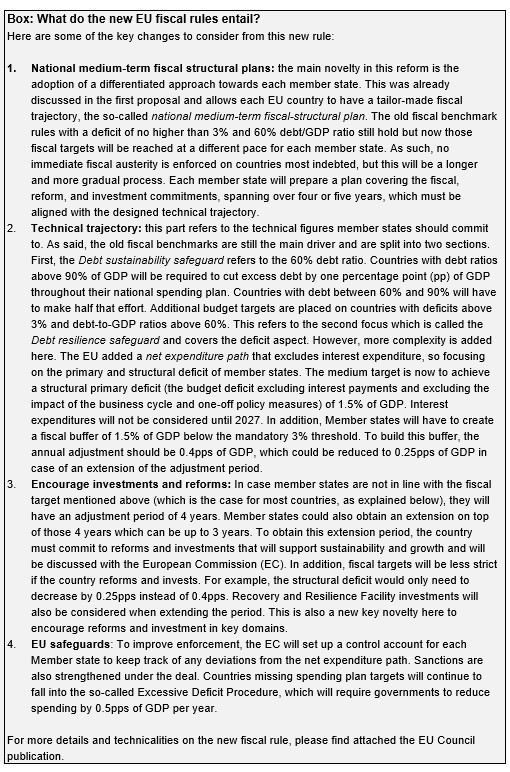

Finally, the EU member states have reached an agreement on a new set of fiscal rules. After a long and heated process, the traditionally divided northern and southern countries managed to find a compromise between fiscal tightening and investment needs. As stated by the EU Council: ‘’The main objective of the reform of the economic governance framework is to ensure sound and sustainable public finances, while promoting sustainable and inclusive growth and job creation in all member states through reforms and investment’’. The new rules will bring fiscal tightening back to the table although less strict than under the previous rules. Fiscal effort will be required, though, and weigh on the economies of the most indebted countries. Therefore, even if this reform in general is positive news for Europe, as it gives more leeway and time to highly indebted countries to normalize government finances, it will be a long and difficult process and could also trigger social tensions along the way. In this note, we will discuss the key takeaways from the new fiscal rules and what they mean for government finances and the economies of the big-6 eurozone countries. We will also shed some light on this rule’s impact on sovereign bond spreads and the forecast for the year 2024.

Will the new rules lead to more or less fiscal discipline?

Whether or not the new rules will enforce more fiscal discipline on the various member states is not straightforward. On the one hand, more flexibility is allowed. Countries can buy extra time to get government finances back into shape by committing to economic reforms and investments. Still, on the other hand, the EC will have a firm finger on the pulse by regularly assessing the fiscal trajectories of the various countries and whether or not these are in line with the national medium-term fiscal-structural plan. Having said that, the most disciplinary element of the new fiscal rules probably is that only countries that adhere to these rules will be eligible for asset purchases under the ECB’s Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). Indeed the TPI (see here) clearly states that only countries that comply with the EU fiscal framework are eligible for asset purchases by the Eurosystem, which means that the sovereign bond spreads of countries that are not in compliance with these rules would probably surge higher in case of a financial or economic crisis that would affect the entire eurozone. This is one of the main reasons why we expect fiscal tightening to materialise this time, although at a very slow pace, as it would be a painful lesson for countries that do not stick to the rules.

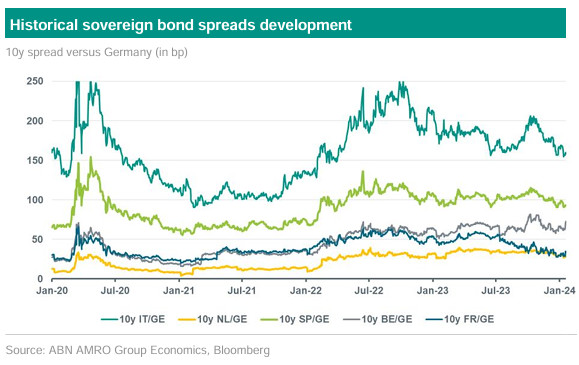

The new EU fiscal rules will be supportive of country spreads in the long term….Last year, the rise in government bond yields brought back into focus the issue of government debt sustainability. However, despite the uncertainty and heightened volatility in 2023, sovereign bond spreads (a measure to account for sovereign vulnerabilities) have remained relatively resilient as shown in the graph below. Indeed, peripheral spreads even outperformed core and semi-core countries during most of 2023 despite the main buyer of government bonds – the ECB – also leaving the market.

One key reason behind this performance is the market expectation of the start of the interest rate cut cycle which provided some light at the end of the tunnel for ‘’risky’’ assets. On top of that, the introduction of the ECB’s TPI in July 2022 (see above) has put a cap on sovereign spreads within the eurozone. The PEPP reinvestments also will remain in place for a bit longer than expected and wind down moderately by EUR 7.5bn per month in H2 2024. Finally, the adoption of the new EU fiscal rule should improve the fiscal outlook for most of the EU countries which should help compress risk premia in the long term.

… but could be painful for some EU countries in the short- and medium-term.

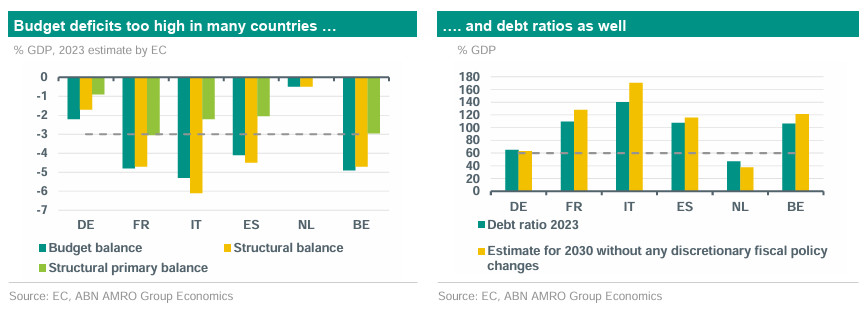

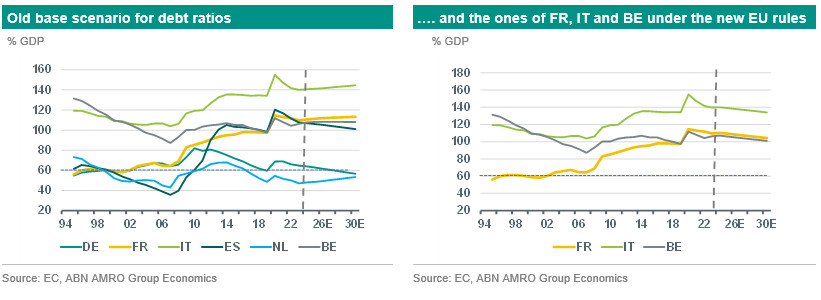

Government finances are fragile in some of the bigger eurozone countries and have deteriorated further during the pandemic and energy crisis when fiscal support was given to households and companies. According to recent EC estimates, the budget deficits of all big-6 eurozone countries besides Germany and the Netherlands were well above 3% GDP and the debt ratios were well above 60% GDP in 2023 (see graph below). The expected level of nominal GDP growth will probably have a downward impact on the debt ratios in the coming years, but the primary budget balance (the budget balance excluding interest payments) and the higher level of bond yields will probably have an upward effect on the debt ratios.

According to our current calculations, the debt ratios of Germany and Spain should decline during the next seven years, whereas those of Italy, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands will rise, as shown in the graph below. For these calculations of the longer-term debt trajectory, we have assumed that GDP growth will be above the potential rate in 2025-26, as growth will rebound from the cyclical weakness in 2023-24. On top of that, growth in Spain and Italy will receive extra support from the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RFF) during the years 2024-2026. In the years after 2026, growth will be close to potential in all big-6 countries. Moreover, we have assumed that eurozone average inflation will be in line with the ECB’s 2% target, and interest payments will gradually increase due to the recent rise in bond yields.

In the Netherlands, the starting point of the debt ratio (48% in 2023) is very low, implying that even with the estimated rise during the next seven years, the debt ratio would remain below the 60% threshold, also because the budget balance of the Netherlands (-1% GDP in 2023) should remain within the -3% limit. Although Spain’s debt ratio was above 90% of GDP in 2023, the downward trajectory in our base scenario would be sufficient to meet the EU fiscal rules. Therefore, only Italy, France, and Belgium are expected to conflict with the EU fiscal rules.

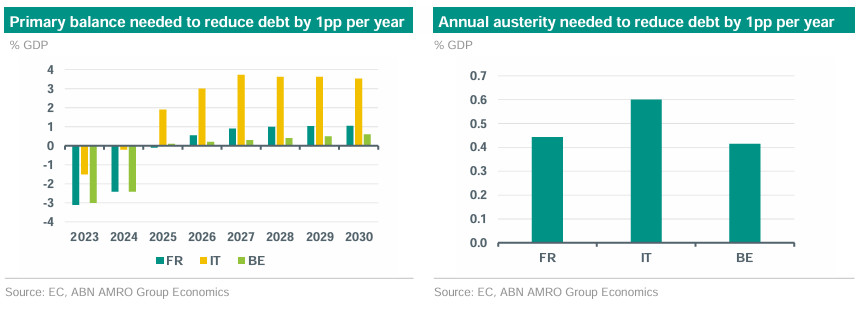

Looking at the adjustment paths for Italy, France, and Belgium under the new EU fiscal rule, which states that they would have to lower their debt ratio (which all were above 90% GDP in 2023) by one percentage point (pp) per year on average throughout the adjustment period (which we assume to be the full 7 years), austerity of around 0.4% GDP would be needed in every year during the next 7 years in France (around EUR 14bn per year) and in Belgium (around EUR 3bn) and close to 0.6% GDP in Italy (EUR 14bn per year). As a rule of thumb, this could lower growth by around half that amount in each year during the next 7 years.

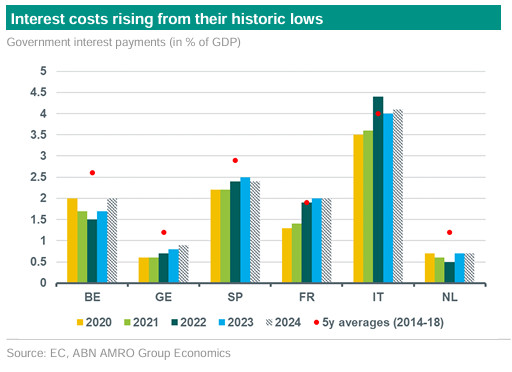

Higher debt service costs will add to the fiscal normalisation challenge

Although the new EU fiscal rules allow interest payments to be discarded until 2027, interest payments will take up a rising part of government expenditure in the coming years. One reason why the rise in countries’ debt ratios since the start of the pandemic has not triggered concern or sustainability issues, is because interest costs were declining at the same time reflecting the lags in the process. Borrowing was cheap. However, as shown in the graph below, interest costs are now rising from historical lows due to the rise in government bond yields. So far, there is no immediate debt sustainability risk in the EU. For most of the big-6, interest payments remain below historical averages (between 2014-18 shown in the graph), with the exception of France and Italy. But the economic and financial situation can deteriorate quickly.

Indeed, the so-called snowball effect on the government debt ratio (the difference between nominal GDP growth and the average nominal interest rate charged on government debt) is looking rather weak, as real borrowing costs have risen significantly over the past year. The low-coupon debt is also maturing, with an average of 15% of the zero-coupon debt maturing this year for most of the big-6. As such, interest expenses will remain a burden in the years ahead for certain governments as it reduces the amount of funding available to invest in more pressing issues like climate change or healthcare.

In the end, restoring fiscal health under the new EU rules will be a long and gradual process. But we think that until national governments play by the rules and engage in fiscal normalisation, this will be constructive for country spreads overall. Of course, some of the fiscal austerity needed could trigger social unrest (e.g. the yellow vest movement in France) and lead to temporary volatile bond yields. However, we deem this effect to be temporary in nature, and until a country’s debt trajectory is on a declining path, we think this will be positively received by the market. A paper from the IMF (see here) also suggests that better macro-fiscal projections can lead to improving market expectations and thus reduce the country’s expected risk premium. This is indeed a development we have recently seen for Greece with a significant improvement in its macroeconomic and fiscal outlook which led the market to reprice its country’s risk premia and led to a significant tightening of the country's spread versus other EGBs.

The interest rate cut cycle will support country spreads in 2024

Most European governments already cut their spending this year compared to last year. However, this is mainly due to the unwinding of the financial support provided to households and companies during the pandemic and the energy crisis. Thus, the ‘’real’’ fiscal tightening is still yet to come. In our view, the start of the ECB interest rate cut cycle, which we expect in June, (see our rates view here), will be the dominant narrative in the bond market this year. This will be positive for ‘’risky’’ assets in general. Indeed, given that the macroeconomic outlook remains relatively benign, with the consensus expecting continuous weakening in economic activity but no deep recession (which is also our view), the interest rate cut cycle will have a narrowing effect on country spreads. As such, we forecast country spreads to tighten slightly toward the end of the year.