ESG Strategist - Uptick of EU GBS will be limited and restricted to a few sectors

The EU Green Bond Standard (EU GBS) is a voluntary standard introduced by the European Commission to enhance the transparency and credibility of green bond markets within the EU. It was introduced as part of the broader EU Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth, with the regulation applying from 21 December 2024. The EU GBS promote the integrity and accessibility of green bonds, enhancing investor confidence, and facilitating the flow of capital toward environmentally sustainable projects, ultimately supporting the transition to a low-carbon economy. By providing a clear definition of what constitutes a green bond, the EU GBS seeks to mitigate the risks of greenwashing, improve the comparability of green financial products, and ultimately drive additional investment into initiatives that align with EU environmental objectives, such as climate change mitigation and biodiversity preservation. Since the application of the EU GBS in late 2024, only three issuers (being one corporate, one financial and one SSA) have used the EuGB label so far (EuGB is the name given to a green bond that complies with the EU GBS). In this piece, we explore the potential for an EuGB market and the additional incentive for both issuers and investors to use the label.

The EU Green Bond Standard (EU GBS) started to apply as of December 2024, and so far only three issuers have issued EuGBs

Our analysis indicates that some EU banks report EU Taxonomy assets that exceed the total amount of green bonds outstanding, implying that issuing EuGB will be easier for some financial institutions

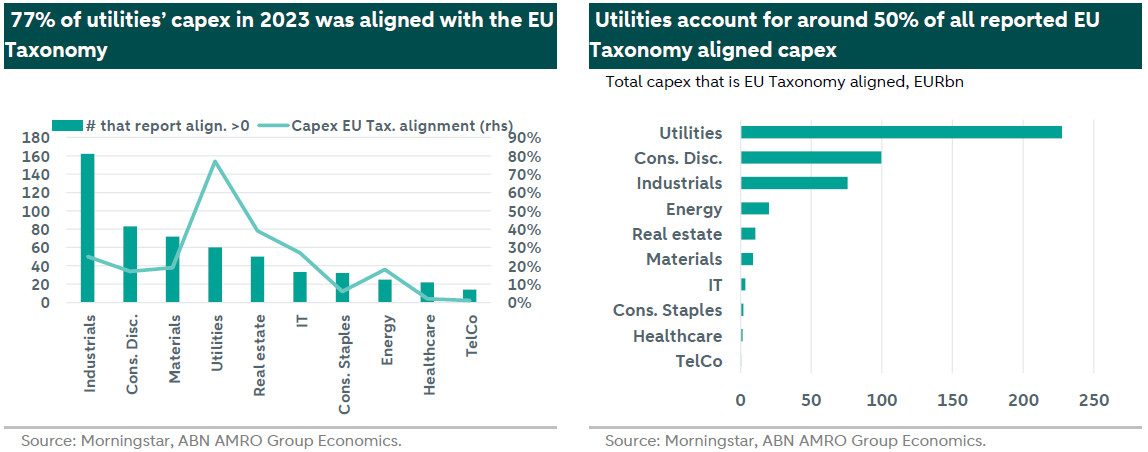

For corporates, alignment with the EU Taxonomy is predominately seen in the utilities sector, with more than half of all reported aligned capital expenditure in 2023 coming from utility issuers

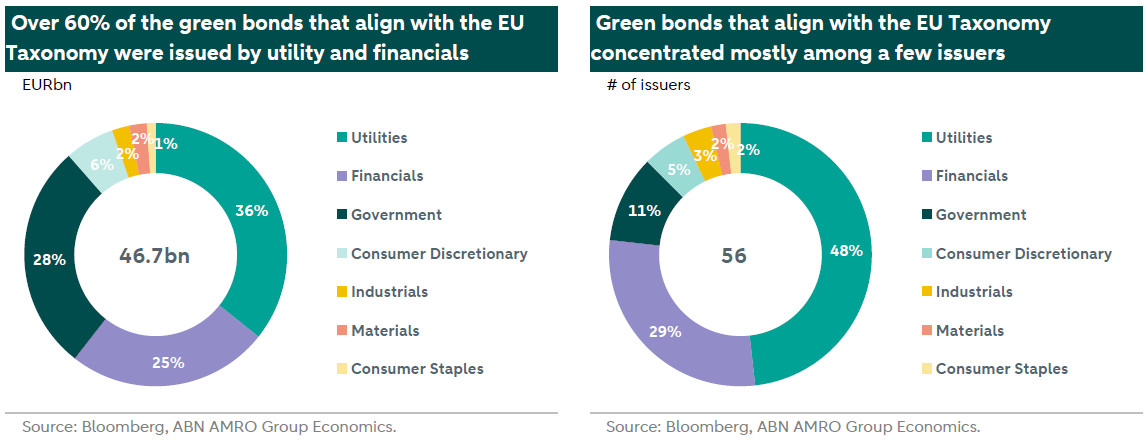

Only 9% of the outstanding green bonds fully align with the EU Taxonomy, while 60% of these aligned green bonds are issued by utility and financial companies

As a result, the EU GBS market appears to be limited to a small number of sectors, specifically financials and utilities, and a few select issuers

Our findings show that the extra costs associated with issuing EU GBS bonds do not seem to be justified by benefits, as the recent EuGB deals have not yet provided issuers with any pricing advantages

On the demand side, regulators have not actively encouraged preferential treatment for EuGBs and/or full EU Taxonomy alignment for sustainable investments, which gives investors the flexibility to invest in regular green bonds alongside EuGBs

Overall we think the EU GBS will remain a niche market, restricted to a few issuers, while the absence of special demand towards these bonds also weakens incentives for issuers to make use of this label

A review of the EU GBS key requirements

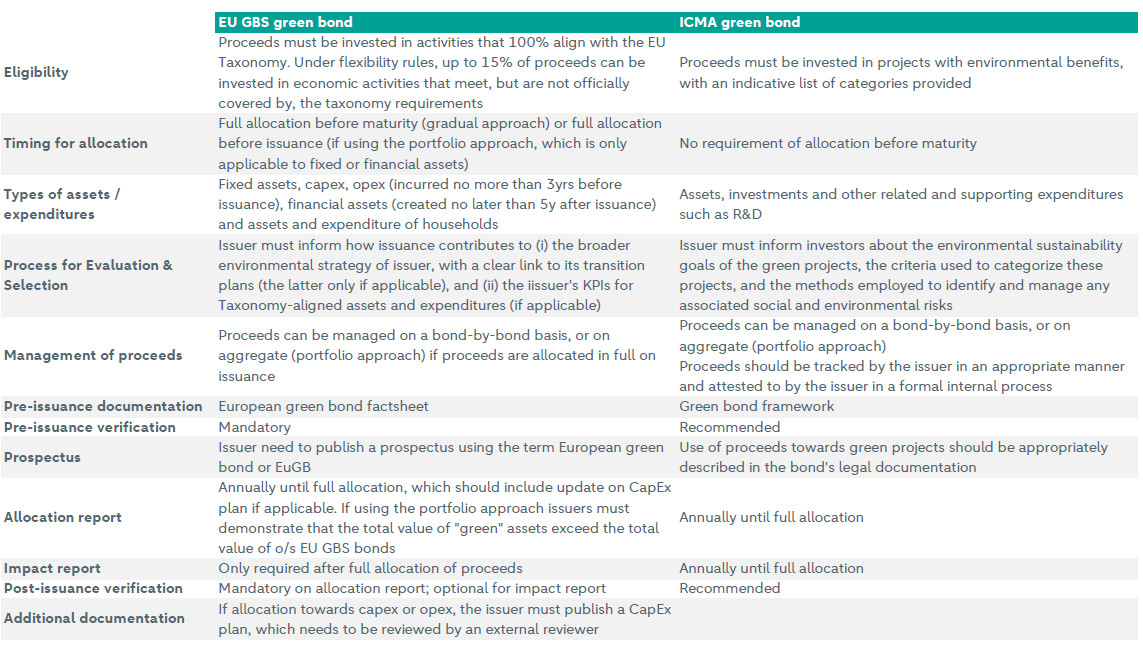

In the table below, we compare the key requirements of the EU GBS with the ones set out by the ICMA Green Bond Principles, which are widely used by “regular” green bonds:

From the table above it becomes clear that the biggest challenge for adoption of the EU GBS lies within the EU Taxonomy requirement. Although there is a flexibility pocket that could potentially allow only 85% of the bond proceeds to be fully aligned with the EU Taxonomy, the European Commission expects only a limited number of issuers to make use of these flexibility rules. That is because, in order to be eligible for the flexibility pocket, 15% of the proceeds can be allocated towards activities:

that are in the context of certain international support in accordance with certain internationally agreed guidelines; or

that do not have a “Technical Screening Criteria” (TSC) available, but meet the generic criteria for “Do No Significant Harm” (DNSH) of the Taxonomy regulation as well as the minimum social safeguards

As such, it is fair to assume that most of EU GBS-aligned green bond (or European Green Bond / EuGB) will be required to ensure all proceeds align with the EU Taxonomy. As such, in order to better understand whether we expect the market for EuGB bonds to pick-up, it is necessary to assess the potential of (green bond) issuers to be fully EU Taxonomy aligned. In the next section, we conduct such analysis on a sector by sector basis.

Assessing the alignment challenge

Financials

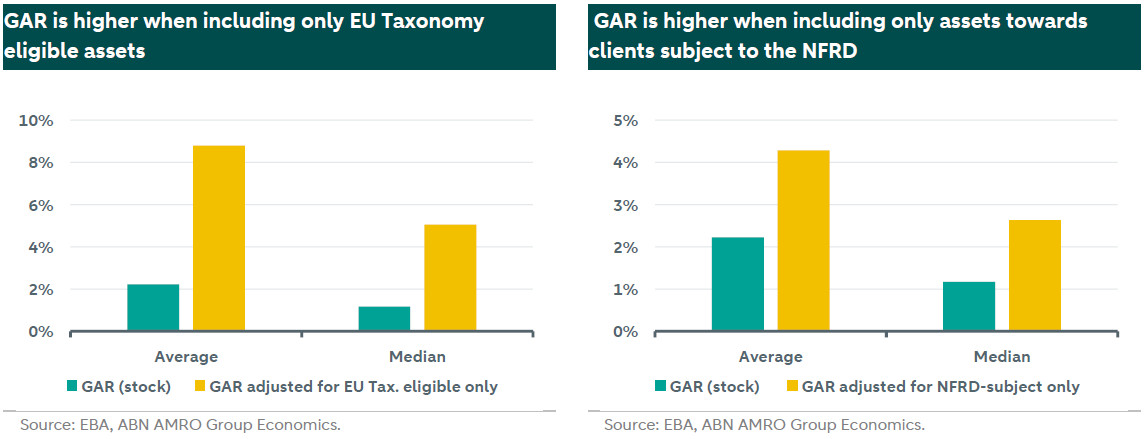

One way of assessing the potential for EuGB issuance is looking at how high the share is of assets that align with the EU Taxonomy. We discussed in a recent piece (see here) how looking exclusively at the Green Asset Ratio (GAR) – a metric that indicates the share of a bank’s assets that is aligned with the EU Taxonomy- could be misleading. For example, not only loans towards activities not (yet) covered by the EU Taxonomy are included in the GAR’s calculation but also the GAR’s denominator accounts for loans to entities that are not subject to sustainability disclosure requirements (NFRD).

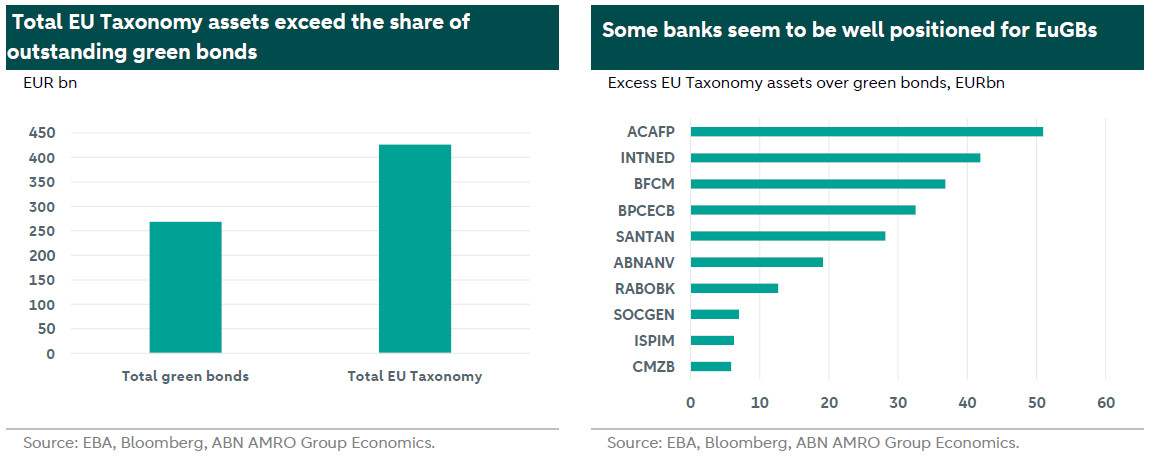

However, we could use the information embedded in the GAR (more specifically, the numerator, or the total amount of assets that align with the EU Taxonomy) to proxy how large the EuGB market could be for EU banks. Hence, we compare this figure (total assets that are claimed to be EU Taxonomy aligned) with the total amount of green bonds outstanding. Interestingly, we see that the former actually exceeds the latter, potentially indicating that the market for EuGBs could be significant for financials. However, a caveat is that this seems to be strongly concentrated amongst a few issuers (see chart below on the right). For example, Credit Agricole, ING and Credit Mutuel all claim to have high EU Taxonomy alignment, which is not fully translated into green bond issuance. These banks however seem to be better positioned for EuGBs, as also exemplified by ABN AMRO’s issuance of the first EuGB by a financial institution earlier this week (ABN AMRO acted as JLM and sole green structuring advisor).

On the other hand, some banks, such as LBBW, Nederlandse Waterschapsbank, Landesbank Hessen and Nordea are among the banks that have a significantly higher share of green bonds outstanding than they do in EU Taxonomy aligned assets. Issuance could become challenging for these institutions.

As such, it seems that the EuGB label offers a wide range of opportunities for some EU banks, but is more challenging to be used by others. From the 107 banks in our sample, 48 (45%) report EU Taxonomy assets that exceed the amount of green bonds outstanding, but only 21 (20%) report an excess amount of over EUR 1bn.

Corporates

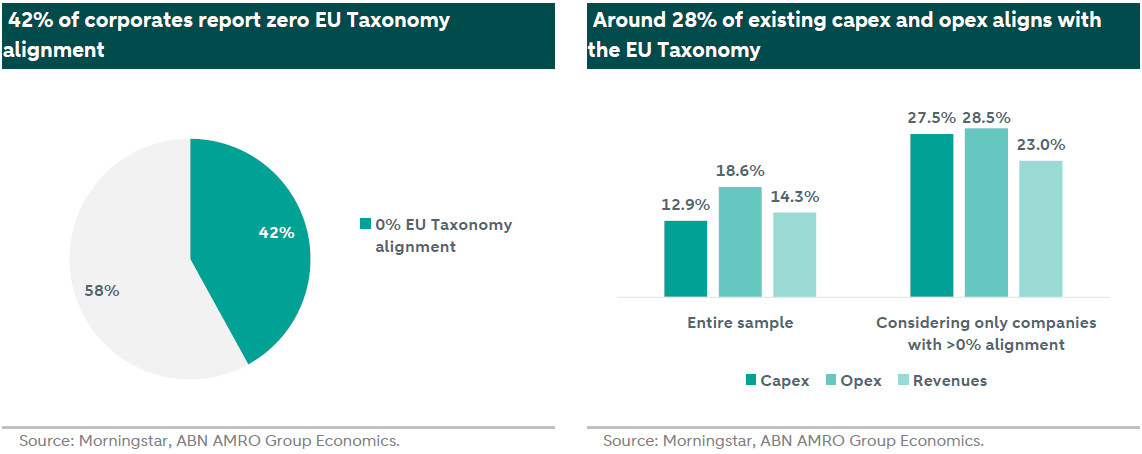

We move our analysis to corporate issuers. According to Morningstar (see ), based on a sample of 1,100 non-financial corporates, only 42% reported an EU Taxonomy alignment that is greater than zero in their 2023 annual reports. From the ones that do report some EU Taxonomy alignment, ca. 28% of the expenditures are aligned, while this is 23% for revenues. As we highlighted at the start of our piece, corporates are to expected to make mostly use of the gradual approach, while for financials this is the portfolio approach. Under the gradual approach, issuers only need to ensure EU Taxonomy alignment before bond maturity, which implies that for corporates, the most important EU Taxonomy alignment ratio refers to capex and opex, rather than revenues and/or existing assets.

Taking a closer look at the reported numbers for EU Taxonomy aligned capex, alignment seem to be very much concentrated in a few sectors. In fact, all but three sectors have capex alignment that is above 25%: utilities, real estate and IT (see chart below). Particularly regarding utilities, 77% of the reported capex is deemed to be EU Taxonomy aligned. This figure is even higher (80%) when looking at only issuers that are active in the green bond market. Overall, that translates in around EUR 450bn of expenditure that could be eligible for EuGB bonds (with ca. 50% of that coming only from utility issuers), which is a relatively small figure when comparing to the amount of euro green bonds outstanding (EUR 1.4tri).

Overall, also for corporates, the EuGB label seems to be very much restricted to a few selected sectors, which would also make the uptick of the label limited. The higher usability of the EuGB label by selected sectors and issuers is exemplified by the first EU GBS-aligned green bond being issued by the Italian utility company A2A.

Only a very small share of existing green bonds are EU Taxonomy aligned

From the outstanding amount of euro green bonds, only a very small share of 9% currently aligns fully with the EU Taxonomy. In terms of issuers, this also seems to be very much restricted to both utilities and financials, which together account for more than 60% of the market.

Given the above, we think that the roll-out of the EU GBS across green bond issuers will still remain very limited, making the EuGB a very niche and restricted market. Furthermore, the above analysis is only based on EU Taxonomy alignment, but issuers could face additional issues. For example in order to issue EuGBs, issuers must prepare a Prospectus Regulation-compliant prospectus, which should specify that the bond is a "European Green Bond" or "EuGB". Currently, issuances that do not require a prospectus (for example, private placements) can still be issued in green format. Furthermore, there is a higher cost involved in issuing EuGBs than in regular green bonds, particularly as the need to comply with regulation requires more extensive legal scrutiny during the issuance process. Also external reviewers might be willing to charge higher costs for the pre- and post-issuance reports as these now fall under the ESMA registration scheme.

EuGB benefits do not seem to outweigh costs

These higher costs could very likely not be compensated by higher benefits. For example, the A2A EuGB issued at the end of January received an orderbook of EUR 2.2bn (bid-to-cover of 4.4x) and was priced 5bps inside fair value. At first, this might indicate strong(er) demand for EuGBs. However, also the Dutch utility company Stedin was in the market two weeks after an attracted a massive demand of EUR 9.8bn (bid-to-cover of 9.6x) on its green bond, pricing it 10bps inside fair value. Overall, excluding the A2A transaction, investment grade euro utility bonds have been placed with an average 4.7x bid-to-cover ratio and priced on average 4bps inside fair value, indicating that the demand towards the A2A bond cannot be fully attributed to the EuGB label.

Looking at the new ABN AMRO, media sources such as Global Capital () have reported that also the first EuGB by a financial institution did not seem to have received any additional pricing incentive from the use of the label. For example, the media platform reports that the deal came in “with no premiums” but that “the tone these days is pricing around fair value”, indicating that the use of EuGB did not seem to have differentiated this bond from other recent deals in the market.

Investors do not have regulatory incentives to invest in EuGBs

On the demand side, there were speculations that regulators would also give preferential treatment to EuGBs. In December last year, ESMA clarified that the assessment regarding exclusions (as required by Paris-aligned Benchmarks – or PAB – which funds with a ESG-related term in its name have to comply with) is applied to green bonds on a “look-through basis” – that is, on an use of proceeds level. This means that, for example, green bonds that finance controversial weapons, tobacco, coal (>1% of proceeds), oil fuels (>10%), gaseous fuels (including distribution) (>50%) and electricity generation with an emission intensity above 100g CO2e/kWh (>50%) are not eligible as “sustainable investments” according to the regulation. However, EuGBs are exempt from such analysis (see ). While at first this might indicate that EuGBs should receive some preferential treatment from investors, it is good to note that almost all (if not all) existing green bonds in Europe are already compliant to this, which also makes the assessment not an additional burden but rather a straightforward exercise. As such, we do not think investors have incentives to also prefer EuGBs over green bonds, which helps to explain the lack of additional pricing benefits we have seen in the recent deals.

Furthermore, ESMA introduced in May 2024 specific thresholds to sustainable investments that investors need to comply with in order to apply any ESG- or sustainability-related term to the fund’s name (). For example, funds using environmental- or impact-related terms should invest at least 80% of its funds in sustainable investments. The latter is still up for interpretation by the investor - that is, it is not mandatory to be linked to the EU Taxonomy. However, ESMA requires investors to fill in an extensive list of questions providing clarification on what that a sustainable investment entails. This includes the need to disclose “to what minimum extent are sustainable investments with an environment objective aligned with the EU Taxonomy” and to explain “why the financial product invests in sustainable investments with an environmental objective that is not Taxonomy aligned” (see ). As such, while the Regulation does provide some support to the investment to EuGBs, as long as investors are able to justify their criteria to what a sustainable investment is, there is also not necessarily any need to ensure full alignment with the EU Taxonomy.

Additionally, one key goal of the EU GBS is to tackle the issue on “diverging rules on the disclosure of information” that harm “the ability of investors to identify, trust and compare environmentally sustainable bonds”. However, the European Commission is putting forward voluntary templates (), which are based on the ones that issuers must fill out when issuing EuGBs. As such, also green bonds can eventually tackle a few of the EuGB goals without having to rely on the official label.

Furthermore, the very limited universe of issuers that will be able to make use of the EuGB label also implies that investors that are heavily invested in EuGB will naturally have investments concentrated in a few sectors and issuers, eliminating the benefits of diversification. This might also help explain why, although the EuGB label is a “nice to have”, it will not necessarily receive preferential treatment by investors.