ESG Strategist - Why EU banks’ Green Asset Ratios may mislead on green alignment

Since January 2024, EU banks are required to disclose ESG-related information under their annual and Pillar 3 reports, the latter being part of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). One of the most important ESG indicator that is disclosed is the Green Asset Ratio (GAR). The GAR indicates which share of a bank’s on-balance sheet total covered assets (exposures that do not include sovereign exposures and trading portfolios) can be considered as environmentally sustainable by aligning with the EU Taxonomy. The GAR is disclosed based on the stock of financial institutions (existing on-balance sheet covered assets) and on the flow (new loans and advances, debt securities and equity instruments). The former informs on the loan book’s current situation, while the latter provides a picture on the potential for future EU Taxonomy alignment. Starting this year, we will also be able analyze these ESG indicators from a historical perspective. While we wait for the 2024 data to become available, we conduct an analysis on the GAR based on most recent data available. We discuss how informative this ratio is for investors to evaluate a banks’ proportion of environmentally sustainable assets and how can it be used to gain better insights into banks’ sustainable activities.

The Green Asset Ratio (GAR) measures how banks' assets align with the EU Taxonomy and was included in 2023 annual reports for the first time

The average GAR across EU banks indicates low alignment with the EU Taxonomy, with significant regional and institutional discrepancies that reflect varied loan portfolios and priorities

However, a closer look at the ratio shows that loans towards activities not (yet) covered by the EU Taxonomy are included in the GAR’s calculation…

…which lowers its value, as we see a positive correlation between the GAR and the share of assets that are covered by the EU Taxonomy

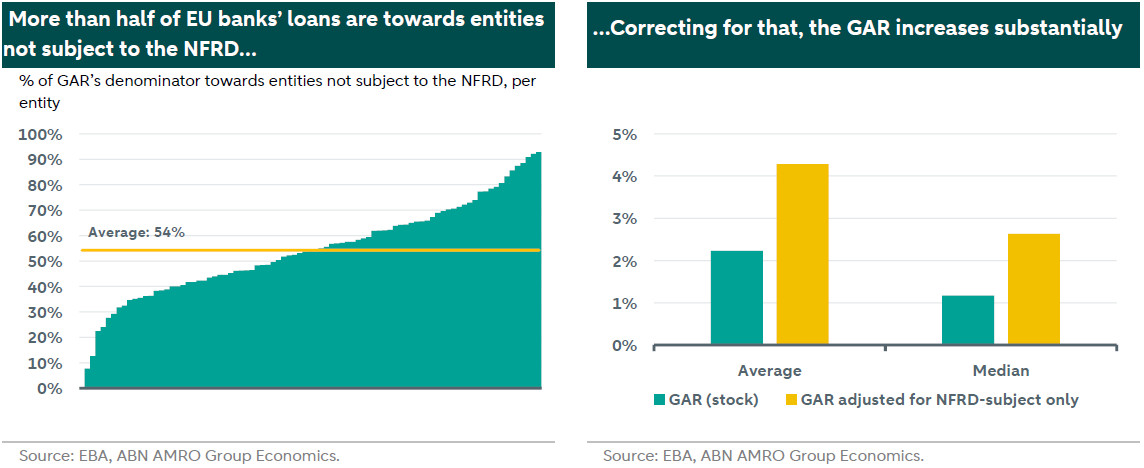

Furthermore, over half of the assets included in the GAR’s denominator are to entities that are not subject to sustainability disclosure requirements…

…but these assets are excluded from the GAR’s numerator, which further depresses the GAR value

Our analysis also reveals inconsistency in ESG indicators calculations among EU banks

As such, we argue that the GAR provides an incomplete picture of banks’ sustainability profile and should be taken with care given data inconsistencies and quality issues that undermine the GAR’s reliability

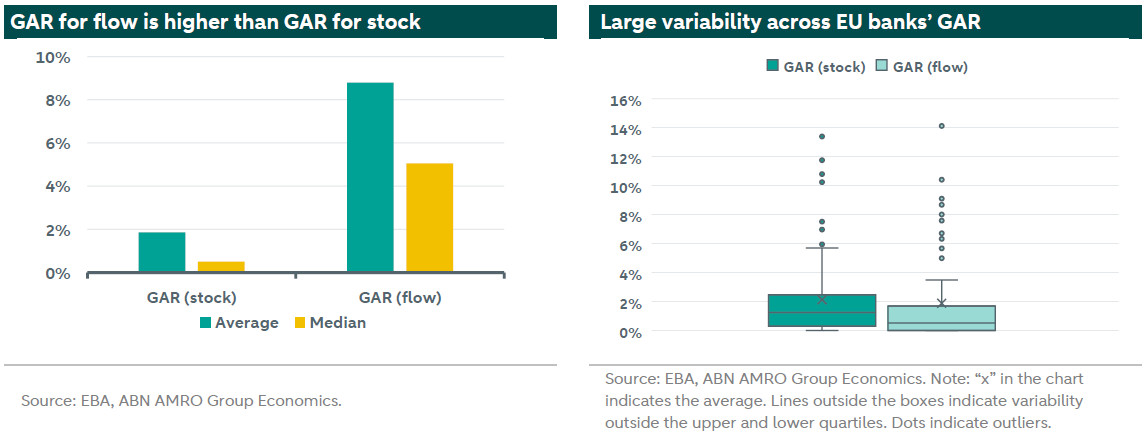

GAR is low and variable across EU banks

Using 2023 data, we gather which banks, from a country perspective, report higher alignment with the EU Taxonomy. On the next page, we present the average and median GAR, relying on both flow and stock indicators.

From the chart above we see that the GAR related to stock is generally lower than the GAR related to flow. That implies that while the existing balance sheet is not as green, it could be considered “greener” when using a forward looking metric that considers also new assets. That is likely the result of more banks having sustainability targets in place, resulting in an expectation that the share of green loans will increase over time. Important to note however that these targets are currently mostly not directly linked to the GAR, and result exclusively from the banks’ own sustainability strategy.

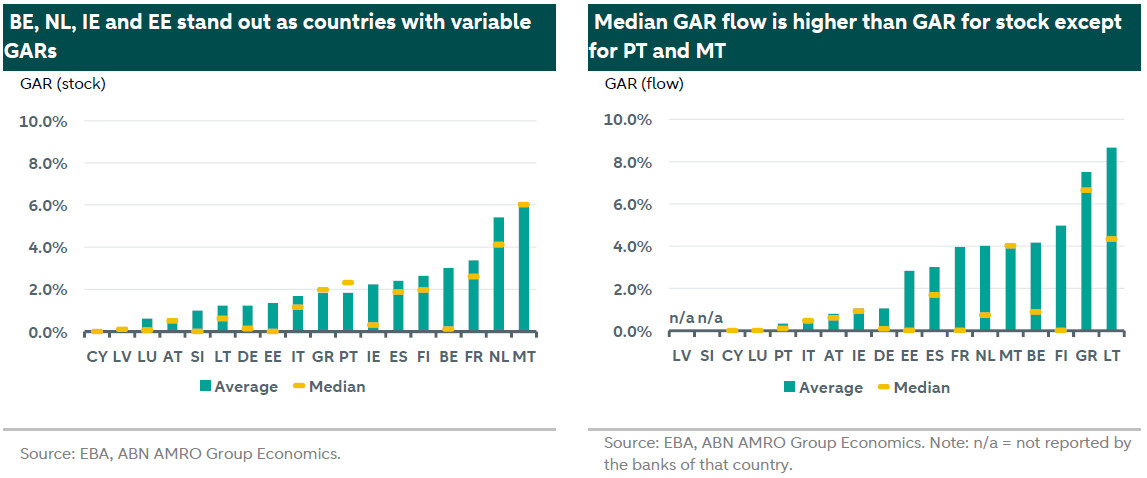

Furthermore, there is overall a large discrepancy in GARs across countries, as indicated in the charts below. Such discrepancy is also captured in the right-hand chart above, where we see a significant difference between the maximum and the minimum values (excluding outliers – the lower and higher lines in the chart). Also across banks within one specific country there is a large variability, as indicated by the significant difference between the average and the median below. The variability in GAR is not only present when looking at the stock, but also the flow (see charts below). Also satisfying the previous analysis is that here we also see that in most countries, the GAR related to stock is generally lower than the GAR related to flow, with exceptions being Portugal and Malta (when looking at the median value). From the charts above, we also see that there seems to be lower variability across banks located in Greece, Austria and Malta, while this is the highest for banks in Belgium, Ireland, Estonia and the Netherlands.

One could argue that the variability in GAR across and within countries is attributed to EU banks being at different stages when it comes to the financing of environmentally sustainable activities. Another potential explanation for this discrepancy is the difference between banks’ lending portfolios. For example, Dutch banks tend to have a higher GAR than peers as most of their portfolios is composed by mortgages, which are easier to be EU Taxonomy aligned given the relatively less stringent threshold and the current regulatory requirements for real estate in Europe, which requires newly build homes to be energy efficient.

Analyzing the GAR requires however some care, as it contains several limitations. On the next page we explore a few of them.

GAR includes loans towards activities not yet covered by the EU Taxonomy

The calculation for the GAR includes also loans towards activities that are not (yet) covered by the EU Taxonomy. This can include ‘green’ (‘transitional’) activities, for which a criteria has not been specified yet, or activities that substantially contribute to non-environmental objectives, such as social objectives. As such, we want to better understand whether a low coverage by the EU Taxonomy can negatively impact the GAR.

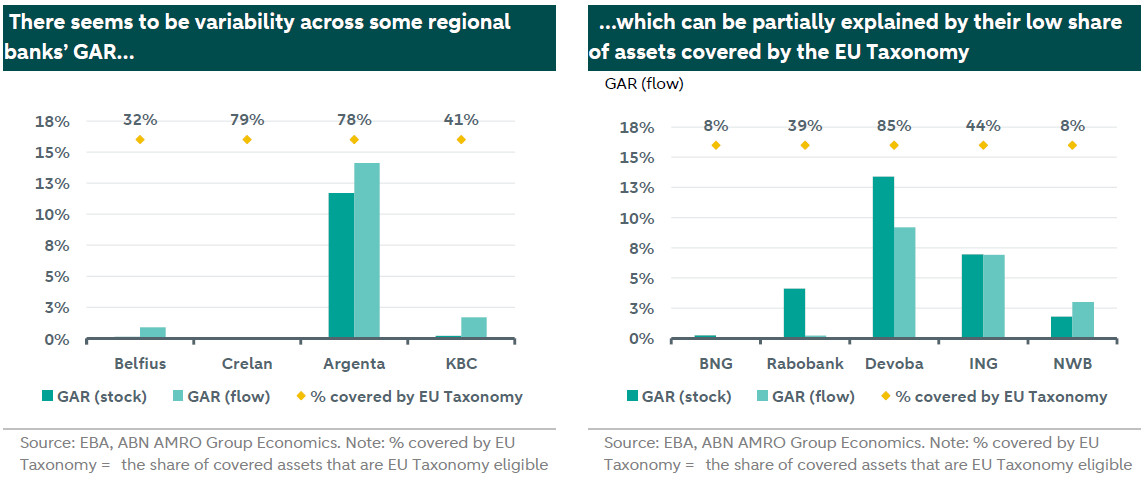

Given the high variability of regional banks in the Netherlands and Belgium, we plot these banks’ GAR with the share of covered assets that are EU Taxonomy eligible to evaluate any relationship.

From the charts below it is possible to see that there seems to be some relationship between these two indicators. For example, BNG’s GAR is close to zero, while also only 8% of its loans are towards sectors covered by the EU Taxonomy. BNG is primarily focused on providing financing to municipalities (ca. 33% of loan book), public housing corporations (ca. 53% of loan book), health care institutions, energy and infrastructure projects and education. As such, it focuses mainly on the social pillar of “E, S and G”. This explains why only a negligible part of its loan book is towards activities that fall under the Climate EU Taxonomy. On the other hand, the Belgian bank Crelan has a very high share of assets covered by the EU Taxonomy (79%), but a GAR of 0%. Also NWB has a very low coverage (only 8%), but a relatively high GAR. For NWB, this stems mostly from the fact that a large share of its counterparties are non-EU based (UK, US, Canada, Japan), and are therefore exclude from the GAR’s numerator (more on this below).

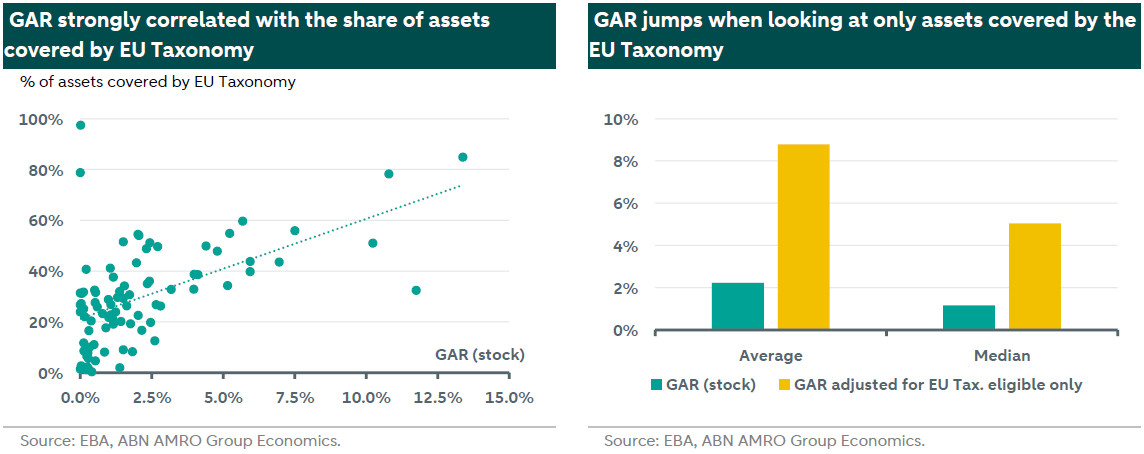

With that in mind, we plot the GAR against the share of covered assets that are EU Taxonomy eligible across the entire universe. As shown on the chart below (left), there seems to be indeed a relationship between these two indicators. That is, banks that focus their financing on activities covered by the EU Taxonomy are also able to report higher GAR.

We then ‘correct’ the GAR by re-calculating it considering exclusively the assets that are EU Taxonomy-eligible . In this case, the GAR is calculated as the amount of EU Taxonomy aligned assets over the amount of EU Taxonomy eligible assets (instead of total covered assets). This “new” GAR (which we called “GAR adjusted” in the right chart above) is significantly higher than the “regular” GAR. For instance, the median GAR increases from 2% to 9%. While still relatively small (the adjusted GAR implies that, from all the assets that are covered by the EU Taxonomy, only 9% can be classified as environmentally sustainable), this demonstrates that referring exclusively to the reported GAR might not give investors the entire picture.

GAR includes loans towards entities that do not report on EU Taxonomy alignment

Besides the fact that the GAR takes into account assets towards activities that are not yet covered by the EU Taxonomy, it also includes within the denominator (but not within the numerator) the assets towards corporates that are not subject to the sustainability disclosure requirements (NFRD/CSRD). This includes SMEs, companies domiciled outside of the EU and non-capital-market oriented companies. By not being subject to these disclosure regulations, these entities have no incentive (from a regulatory perspective) to assess to what extent can their activities be classified as environmentally sustainable. Furthermore, by being excluded from the numerator of the GAR, even if this data is (voluntarily) disclosed, they are not to be included in the sum of sustainable loans.

With that in mind, we calculate the share of these assets that are included in the GAR’s denominator but excluded of its nominator. This is presented in the right chart below. Most of the banks in the EU seem to finance entities that do not have to provide sustainability reporting. And as these assets are excluded from the numerator, they bring the GAR value down. Correcting for this already provides a large upside to the GAR, as shown on the right chart below.

Important to note that the EBA also imposes banks to disclose (as of reporting date of 31 December 2024) the Banking Book Taxonomy Alignment Ratio (BTAR). The BTAR is a similar metric to the GAR, but includes exposure to entities not subject to the sustainability disclosure regulations also in the numerator, for consistency purposes. As such, the BTAR may address some of the GAR limitations, but will also not provide a complete picture of banks’ sustainable activities. That is because it remains unlikely that these entities will (voluntarily) provide the necessary sustainability data for banks to classify these loans as environmentally sustainability.

Data quality on reported GAR remains an issue

During our analysis, we also encountered several data quality issues. For example, the reported “% coverage” indicator of Template 6 is sometimes calculated as the amount of EU Taxonomy-aligned assets over the bank’s total assets, and sometimes as the share of assets included in the GAR’s denominator over the bank’s total assets. This results in significantly different figures. For example, the Italian bank ABANCA reports a “% coverage” of 75%, which is calculated using the latter methodology. However, this falls to 2% when calculated using the amount of total EU Taxonomy-aligned assets. The EU Taxonomy is a fairly new regulation, so lack of clarity on how to interpret the legal texts results in banks sometimes having different interpretations. This is also not exclusively applied to banks. The data that serves as input for banks (coming from, for example, corporates that are also required to report on EU Taxonomy alignment) can also contain data quality issues, which ultimately also brings into question the trustability of the GAR.

Moreover, collecting data from clients can also be challenging. This ultimately results in banks having to also rely on internal assumptions. For example, insurance companies are not required to report the breakdown of alignment/eligibility per environmental objective, while banks do need to report that. Hence, as data quality remains a challenge, investors should also be careful when relying exclusively on the reported GAR.

Can we trust the GAR?

Under the ESG disclosures of (amongst others) the Pillar 3 report, banks also need to disclosure which share of the EU Taxonomy-aligned assets that are considered to be towards environmentally sustainable transitional activities. A transitional activity is classified as “an economic activity for which there is no technologically and economically feasible low-carbon alternative” but supports the climate transition consistent with a 1.5 degree pathway. Some banks report this share as relatively high (>60%), mainly: Bank of Ireland (100%), Deutsche Pfandbriefbank (96%), Bankinter (62%) and BNP Paribas (63%). For Bank of Ireland and Deutsche Pfandbriefbank (pbb), the share close to 100% indicates that basically all of these two banks’ sustainable loans are towards transitional activities, which is also an important information for investors. Still, it remains unclear what kind of activities are considered transitional by these banks. For example, pbb mentions that the activities relevant for assessing alignment with the EU Taxonomy are: new construction, renovation of existing buildings and acquisition and ownership of buildings. Real estate activities are not considered to be transitional, as there it is possible to decarbonize these assets to align with a 1.5 degree pathway using “technologically and economically feasible” technologies. As such, also better understanding how the assessment with EU Taxonomy (and other sustainability-related screenings) have been done should be an important point of attention to investors.

Conclusion

Our analysis shows that the GAR does not provide a complete or meaningful representation of banks’ environmentally sustainable activities. Its limitations - including variable calculations, exclusion of certain asset types / counterparties, inconsistencies in reporting, different legal interpretations of the compliance with the EU Taxonomy, etc - hinder its effectiveness as a reliable metric for investors. Against this background, we think that the Taxonomy alignment reported in the GAR is not meaningful with regard to the actual proportion of assets that finance environmentally sustainable economic activities. Most banks are still in their transition to become sustainable, and the GAR is a step forward into allowing investors to assess where these entities stand and where they expect to be in the future. However, its several limitations, data quality issues and overall trustability issues imply that the GAR might not be an accurate measurement to evaluate the sustainability strategy of banks. It is unclear at the moment whether these issues will be resolved, also considering that the European Commission is now undertaking a throughout review of all its sustainability-related regulations. As such, for now, a comprehensive analysis, potentially using additional indicators, is essential for accurately assessing banks' alignment with the EU Taxonomy and their progress toward sustainable financing.