ECB shows that transition risks will have a significant impact on corporates and banks

The ECB stress-tested the economy under different transition scenarios over an 8-year horizon. Corporates are affected by transition risks through lower profitability and higher leverage, which result in higher credit risk. This increased risk ultimately feeds into banks’ own credit risk, which could lead to significant expected losses. Transition risk for the banking sector in the euro-area is very much concentrated within a few large banks.

The ECB published a paper which stress-tests the economy under different transition scenarios over an 8-year horizon

It combines non-climate developments from macroeconomic projections with climate-related shocks identified by the NGFS, while focusing on the short-term impacts (ie before 2030).

We focus on the impact on corporates and banks in this paper

The ECB shows that corporates are affected by transition risks through lower profitability and higher leverage, which result in higher credit risk. This increased risk ultimately feeds into banks’ own credit risk, which could lead to significant expected losses

The ECB paper also shows that transition risk for the banking sector in the euro-area is very much concentrated within a few large banks

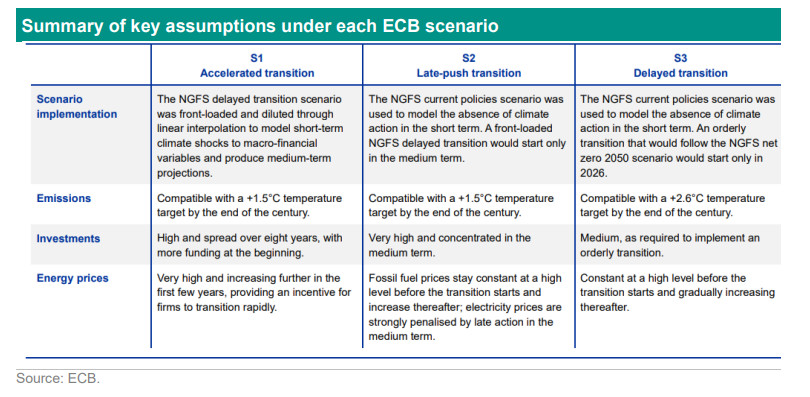

The ECB published a paper earlier this month where it shows the impact of different transition scenarios in the EU economy from 2022 until 2030 (see ). The scenarios were defined as following: an “accelerated transition” scenario, which assumes that a green transition starts immediately, allowing a reduction in emissions by 2030 in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement; a “late-push transition” scenario, which assumes that adverse macroeconomic developments lead to a green transition starting only in 2025 (but is still intense enough to achieve Paris-aligned emission reductions by 2030); and a “delayed transition” scenario, which also starts only in 2026, but would be “ smoother” (being therefore less costly in the short-term), meaning it would not be sufficiently ambitious to reach the Agreement goals by 2030. The scenarios were based on the NGFS scenarios framework, with a few key adjustments:

the “accelerated transition” scenario assumes that the NGFS “delayed transition” scenario starts already as of 2023, instead of 2030;

the “late-push transition” scenario assumes that until 2025, the economy follows the NGFS “current policies” scenario, but aligns with the NGFS “delayed transition” scenario from 2025 onwards

the “delayed transition” scenario assumes that until 2025, the economy follows the NGFS “current policies” scenario, and that the NGFS “net zero 2050” scenario would start in 2026

A summary of the scenarios used by the ECB can be found on the table below.

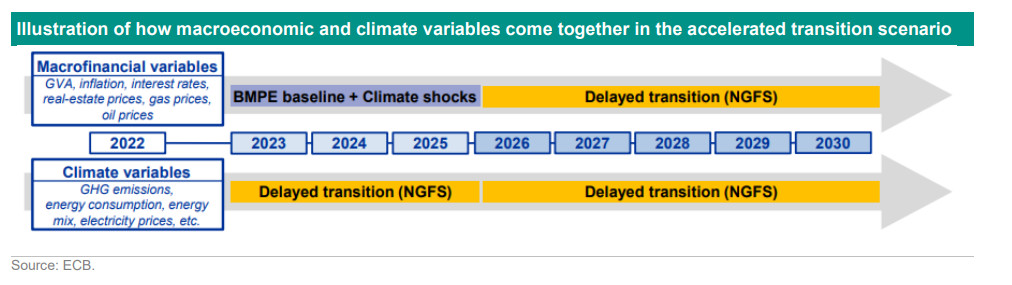

The innovative aspect of the ECB’s paper is that it (i) combines non-climate developments from macroeconomic projections with climate-related shocks identified by the NGFS, and (ii) focuses on the short-term impacts of transition risk (ie by 2030). The overview below also illustrates how the ECB has combined macroeconomic developments with climate variables (in this specific case, for the construction of the “accelerated transition” scenario).

Below, we highlight the key take-aways focusing first on corporates, and then on banks.

1. Corporates

The transition to a low-carbon economy affects firms’ profitability and leverage

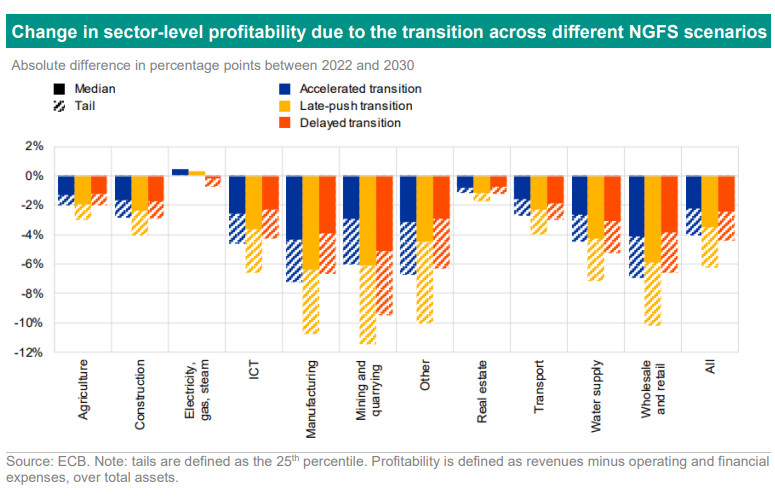

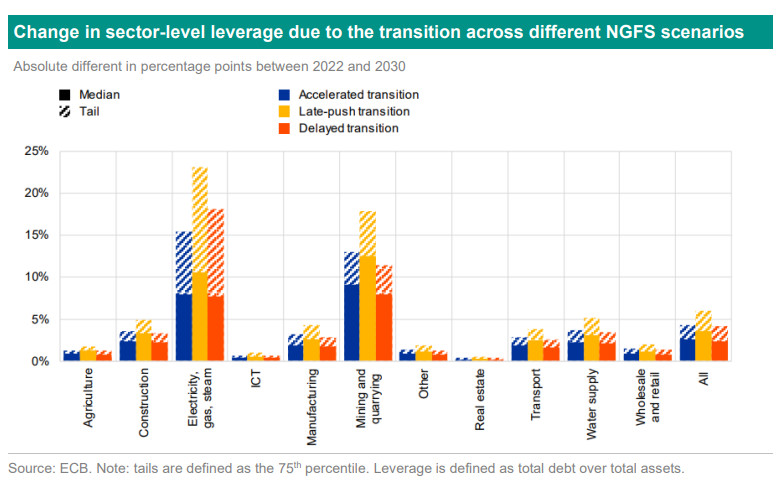

The transition to a low-carbon economy will affect corporates in the EU through: (i) lower profitability, coming from a supply-side, and partially carbon tax-induced, energy price shock (higher oil and gas prices), which would add to firms’ production costs and operating expenses; and (ii) higher leverage, as firms need to invest in carbon mitigation activities to replace their current stock of brown assets and reduce their carbon footprint. These investments are assumed to be mostly funded via bank loans. The charts below highlight the ECB’s findings in terms of the impact for both, profitability and leverage, across different sectors, across the different scenarios.

A late-push transition would lead to energy prices similar to those experienced during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which will result in a severe deterioration in profitability, in particular for energy-intensive firms. The profitability impact in the delayed transition scenario is not as severe given that the impact is likely to be felt by firms after 2030. Overall, the ECB analysis indicates that profitability would decrease by 2 to 3 percentage points for the median euro area firm, and by twice as much for the median firm in energy-intensive sectors (e.g. mining, manufacturing and retail) and for firms in the tail of the distribution. Furthermore, as we previously mentioned, higher investments into the energy transition will also increase firms’ indebtedness, which will be higher for firms that require a larger scale of transition (mostly mining and electricity). In general, the ECB concludes that the leverage ratio would increase by around 3 to 4 percentage points for the median firm across sectors in the euro area, while it would increase by 3 to 4 times as much for the median firm in the mining and electricity sectors.

The ECB findings are also in line with previous research that ABN AMRO has conducted. For example, by using scope 1 and 2 emission data, we were able to see which sectors are mostly vulnerable to an increase in energy prices from an EBITDA margin perspective (see ).

Additionally, cumulative investments until 2030 would reach higher levels under the late-push scenario compared to the accelerated transition due to the later start of the transition, which would induce a slower learning curve for renewable energy production and therefore more expensive investments. This is particularly costly for electricity firms. Nevertheless, both scenarios result in the same amount of installed capacity of renewable energy by 2030. On the other hand, while the cumulative investment under the delayed transition scenario is expected to be lower (around EUR 2.5tri vs. around EUR 3tri for the other scenarios), that is because installed renewable energy capacity is also estimated to not reach the same levels as under the other two scenarios. In fact, the ECB estimates that renewable energy capacity under the delayed transition scenario will be 2,000 GWh less than in the other scenarios.

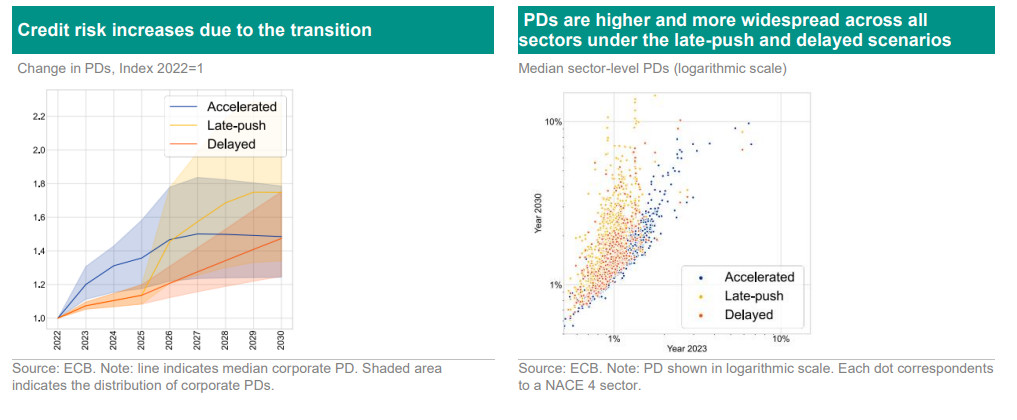

Higher leverage and lower profitability feed into higher credit risk

The increase in leverage and the decline in profitability can be then translated into higher probabilities of default (PDs), which are used as a proxy to capture credit risk for these corporates. As shown in the charts below, corporate PDs would increase the most under the late-push transition scenario. The chart below shows that, although credit risk by 2030 is lower for the delayed transition scenario, it is expected to increase further and reach its peak after 2030. On the other hand, under the accelerated and late-push transition scenarios, credit risk would already start to decrease in the second half of the period. Overall, the delayed transition scenario implies not only that transition risk would continue to negatively affect corporations for a longer period, but also that physical risk would have a stronger effect on the economy (recall: under this scenario, temperatures are not expected to achieve the reductions required as per the Paris Agreement). Furthermore, the chart below (right hand side) also show that the distribution of corporate PDs would also be wider under the late-push scenario, indicating more extreme behaviours in the tails.

2. Banks

Euro-area banks are very vulnerable to transition risks

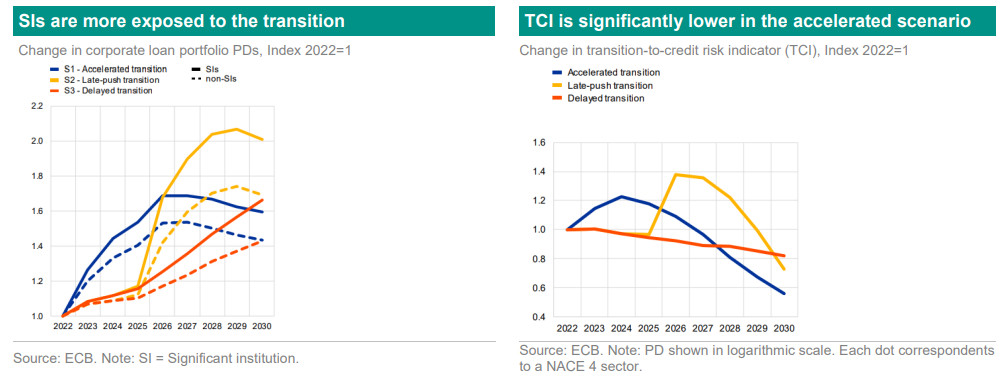

The ECB computed the PD of a bank’s loan portfolio by using the PD of corporates (as previously shown), weighted by the bank’s exposure to that corporate (for that, it used AnaCredit – the euro area credit register). The data was then aggregated at bank level.

The results indicate that:

40% of the total loan volume of the euro area banking system is towards energy-intensive sectors (this is greater for significant institutions (SI) - around 42%)

Less than 10% of all banks account for 90% of all exposure to energy-intensive sectors, indicating that transition risk will be heterogenous across banks

The top 10% of the banks with highest exposure to energy-intensive sectors account for one-third of the total lending in the euro area

Overall, the ECB paper shows therefore that the euro banking system is very exposed to transition risk (and that transition risk increases the bank’s credit risk), but that this risk is mostly concentrated within a few (large) banks (known as significant institutions, or SIs, as shown in the chart below, on the left hand side)

Furthermore, the ECB paper shows that under a scenario where the Paris Agreement goals are reached by 2030 (accelerated transition and late-push scenarios), the peak in bank’s credit risk increase will be reached before 2030, and will slowly start to return to “normal” levels thereafter (see chart above on the left hand side). However, under a delayed transition scenario, transition risk, and thus credit risk, is expected to continue to increase after 2030 (and this is also when physical risk is also expected to start to feed within PDs).

Credit risk might be similar across different scenarios, but exposure to climate risks are very different

The paper also makes use of a metric called “transition-to-credit risk intensity” (TCI), which is calculated as the product of the borrower’s GHG emissions and (projected) PDs, weighted by borrowers’ loan exposure. This metric captures therefore not only the bank’s credit risk (corporate PD weighted by the bank’s exposure), but also transition risk (proxied by emissions), serving as a metric to assess both, banks’ “point-in-time” exposure to credit risk, as well as their forward-looking exposure to transition risk in terms of outstanding CO2 emissions. By looking at TCIs, we see that despite credit risk from banks reaching similar levels by 2030 under the accelerated and delayed transition scenarios (see chart above on the left hand side), the transition-to-credit risk intensity is actually significantly lower under the accelerated scenario (see chart above on the right hand side). This indicates that, while a late-push scenario would affect banks’ credit risk more severely by 2030 (in comparison to delayed transition), the long-term transition and physical risk implications would be more acute under a delayed transition scenario. All in all, the analysis shows that while different transition paths can result in similar credit risk levels in the economy by 2030, exposures to climate risks are very different.

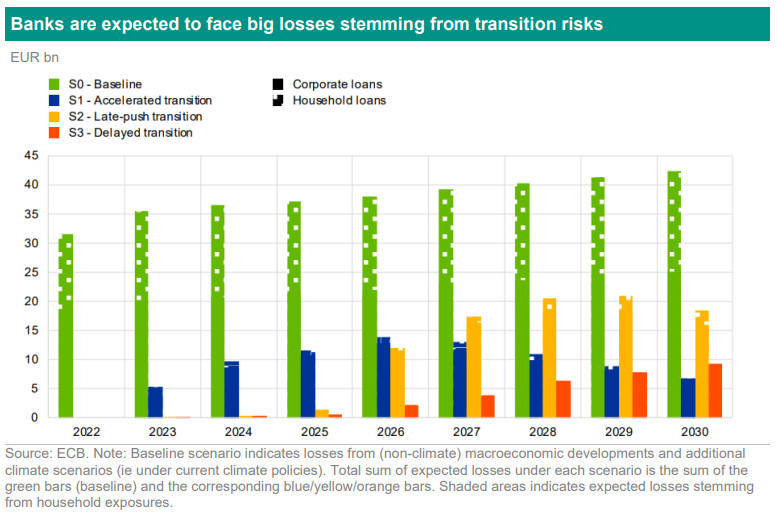

Furthermore, the ECB paper estimates that annual losses for banks from transition risks in the short-term (which include then corporate loan portfolios, as well as exposures to households) could amount to as much as EUR 21bn under a late-push scenario, which contrasts to EUR 13bn for the accelerated transition scenario. Under the delayed transition scenario, expected losses could reach EUR 9bn up to 2030, which is lower than the other two scenarios due to milder transition efforts. However, this is expected to increase further after 2030 due to greater long-term transition and physical risks, while under the late-push and accelerated transition scenarios, banks’ losses are expected to peak before 2030. The expected losses are estimated as “additional” to the already-estimated losses using macroeconomic developments as per forecasts from BMPE projections, and climate variables as per the NGFS “current policies” scenario, where no additional transition risk being accounted for (green bars in the chart below).

The total expected annual losses (that is, excess transition risk losses as well as losses stemming from macroeconomic developments and current climate policies – the “baseline scenario”) could amount to as much as EUR 65bn under the late-push scenario.

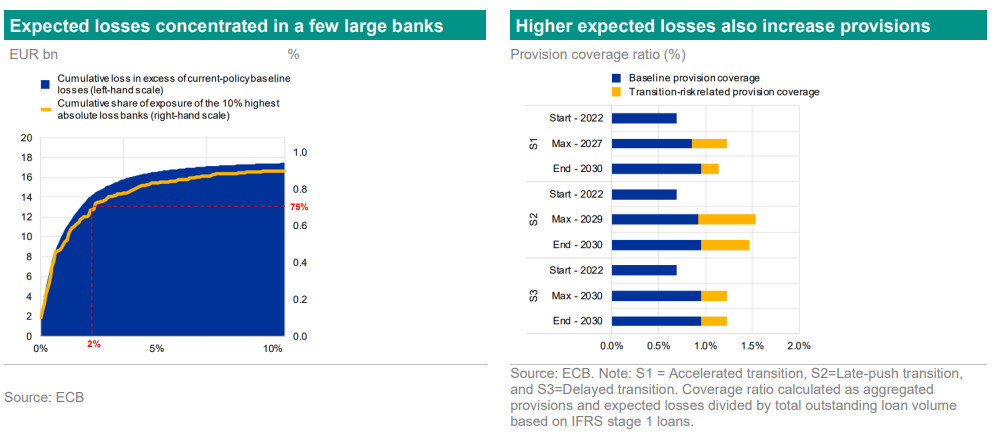

Exposure to transition risks is concentrated within a few banks

As previously noted, the ECB does not expect banks’ losses in the euro area to be homogenous. Under the late-push scenario, the central bank expects 10% of the banks to see annual expected losses almost double by 2030 compared to 2022 levels, with half of this increase stemming from transition risks. Zooming into the 10% banks that have the highest absolute expected losses (i.e. “tails” of the distribution), the ECB concludes that 2% of these banks account for 75% of all total expected losses by 2030, while also accounting for 65% of total loan exposures in the euro area (see chart below on the left hand side).

Expected losses are covered via provisions – hence, the provision coverage ratio (provisions overt total loan volume) for banks’ are estimated to increase from 0.69% in 2022 (stage 1 loans) to almost 1.5% until 2030 in the late-push scenario (see chart below).

On aggregate, the annual losses for the median bank stemming from transition risks over the next eight-years would range between 0.6% and 1% of the portfolio, but would be double that for the 10% of most vulnerable banks, pointing to a limited impact relative to portfolio size and capital generation capacity of the banks concerned.

This article is part of the SustainaWeekly dated September 18th 2023