China - That 2018 (tariff) feeling – What’s different in 2025?

Just as growth momentum is showing some signs of recovery as we near the end of 2024 , an expected rise in US tariffs under Trump 2.0 will create more drags to GDP growth in 2025. We assume a bigger tariff shock compared to 2018-19, with build-up to an average rate of 45%. But China is now less dependent on the US, has developed a playbook to react, and will add stimulus. We expect annual growth to slow from 4.9% in 2024 to 4.3% (was 4.5%) in 2025 and 4.2% in 2026.

Just as growth momentum is showing signs of a recovery as we near the end of 2024…

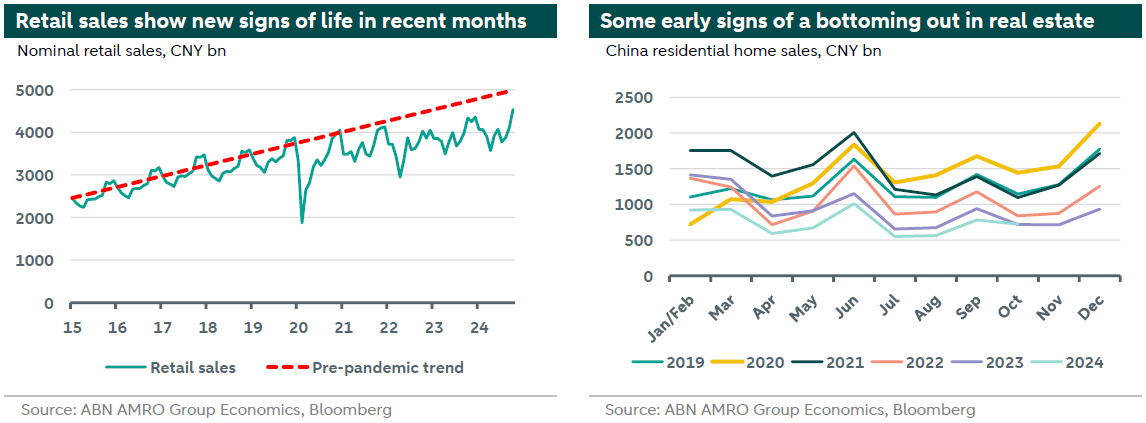

With headwinds from the property downturn ongoing, real GDP growth slowed to a six-quarter low of 4.6% yoy in Q3-24 (Q2: 4.7%). That said, quarterly growth picked up to 0.9% qoq s.a. (Q2: 0.5%), while activity data for September/ October and the October PMIs suggest that growth momentum is regaining some strength as we near year-end. This partly reflects Beijing’s recent pivot from industrial policy to demand management (see below and here). Improve-ments at the demand side are particularly interesting: retail sales growth is picking up, fixed investment growth is stabilising, and the PMI order components are improving. There are also signs that the property sector could be reaching a bottom: in October, for the first time since May 2023, residential home sales were higher than the same month one year earlier. Export growth was also strong in October, but imports remain weak. On the monetary front, inflation remains subdued and lending growth has slowed further. Still, recent data are in line with our forecast that quarterly growth will pick up materially in Q4, partly reflecting payback from weakness in the previous two quarters. We expect annual growth for 2024 to come in just below target, at 4.9%.

…an expected rise in US tariffs under Trump 2.0 will create more drags in 2025

The Republican sweep in the US elections (gaining the presidency and full control of Congress) brings additional risks for China, with China hawks Rubio and Waltz in the running for secretary of state and national security advisor. Incoming President Trump does not even need parliamentary control: in 2018 he used the presidential powers under Section 301 of the 1974 US Trade Act to install specific China tariffs. We assume the US will announce a new round of high (headline 60%) China tariffs in Q1-25, start implementing them in Q2-25 and gradually expand their coverage until an effective average tariff rate of 45% (60% over 75% of CN exports to US) is reached in Q2-26. That’s almost a quadrupling in comparison to the rate seen at the end of the first tariff war in 2019, and a fivefold increase compared to the current effective average rate of ±9% (also see lead article). Other measures such as a further tightening of export controls and investment restrictions beyond the current ‘High Fence, Small Yard’ strategy are also likely. All these moves will sharply accelerate a US-China decoupling of trade and investment flows, and ex ante form a larger shock compared to 2018-19. Trump’s first tariff war was followed by a 20% drop of US imports from China in 2019-2020 (also reflecting the impact of the pandemic), although there was a clear rebound in 2021-2022. Next to effects on trade flows, a new US-China tariff war may also undermine Beijing’s efforts to improve sentiment/confidence.

Still, China now looks better prepared compared to the first tariff war in 2018-19…

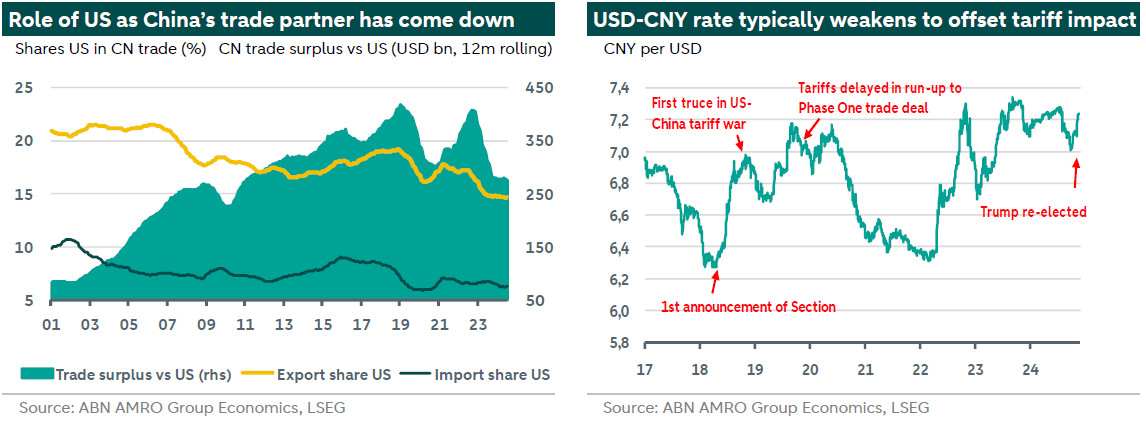

Still, though the shock is larger, China now looks better prepared for a tariff war than in 2018. Through trade diversification, China has become less dependent on exports to or (crucially) imports from the US (see chart). China has also developed a toolkit of countermeasures. Beijing may perhaps not respond proportionally to new tariffs, but it could target the ‘Trump base’ in rural areas by raising tariffs on agricultural products again. Other potential retaliation tools are blacklisting specific US firms, restricting access to critical inputs such as rare earths, and FX depreciation. During the first tariff war, the yuan fell by 15% versus USD between March-18 and September-19 (see chart). We expect the PBoC to tolerate more CNY weakness to offset the new tariffs again (USDCNY forecast per end-25: 7.80), although the PBoC will likely step in should the depreciation get disorderly. In fact, the CNY has already weakened versus USD since Trump’s re-election, but that also reflects general dollar strength. While we do not expect CNY depreciation to fully offset US tariffs, a substantial weakening would benefit China’s broader external competitiveness.

All in all, we assume a flaring up of the US-China tariff war to lead to new GDP headwinds, with some nuances. First, in the short-term, the threat of tariffs typically leads to trade frontloading, which would benefit Chinese net exports and GDP growth initially. Second, the first tariff war showed that after a while exports destined for the US are partly diverted through third countries like Vietnam or Mexico (see China: A tale of Trump risks, tariffs and trade diversion). Third, China may be able to shift (part of its) exports to other destinations than the US, although there is a risk that some countries will try to push back against an (even bigger) surge in imports from China, particularly for some sensitive products. Fourth, given the potential impact of China’s countermeasures on US firms (including Musk’s Tesla) and Trump’s electorate, and the effects of high/broad tariffs on US inflation, there is also a possibility that both countries, after an initial escalation, will start to work towards some kind of a deal, or a truce – similar to events in 2018-2019.

… and we expect Beijing to step up fiscal support further to offset tariff risks

With the economy stuck in low gear, Beijing finally decided to pivot from industrial policy to demand management over the summer. Following a PBoC package in late September, all eyes turned to fiscal stimulus. Judging from previous policy statements, Beijing aims to break negative feedback loops, while putting a floor under real estate and equity markets. This should help restore confidence among consumers/homebuyers, producers, and investors, thereby supporting domestic demand. Beijing tries to do this ‘indirectly’ by repairing the financial position of local governments, large state banks and (state-owned) property developers. Direct consumption support looks limited so far (to the poorest, and to students), but this may be stepped up should downside risks rise. Financing is said to take place via issuance of ultra-long central-government bonds and special local government bonds. So far, Beijing follows a stepwise approach in adding fiscal stimulus rather than instantly presenting a ‘bazooka’ package. A CNY 10trn package to repair local government finances announced on 8 November was followed by a housing tax cut the week after. One of the next steps could be a recapitalisation of the largest state banks. All in all, we expect more fiscal stimulus to follow under this stepwise approach. This enables Beijing to finetune support with actual developments in activity and sentiment, while keeping part of its powder dry for when more is known about Trump’s tariff plans and their impact.

We expect annual growth to slow to 4.3% in 2025 (was 4.5%) and 4.2% in 2026

The assumed gradual building up of US tariffs would be negative for net exports, and possibly also for consumer and business confidence. On the other hand, a pick-up in quarterly growth in Q4-24 and Q1-25, partly boosted by trade frontloading, is putting the Chinese economy on a more solid footing. On top of that, we assume CNY depreciation and a stepping up of fiscal stimulus to act as offsetting forces. All in all, we expect annual growth to fall from 4.9% in 2024 to 4.3% in 2025 (was 4.5%) and to 4.2% in 2026. Given the remaining uncertainties regarding for instance US tariffs, risks surrounding these forecasts have obviously risen following the US elections, and are tilted to the downside.