US Watch – Trump also increases risks to labour market

Trump immigration and government employment policies increase downside risks to the economy. The labour market is expected to see a mismatched decrease in both demand and supply, leading to an increase in both the unemployment and vacancy rate. The feared inflationary impact of labour market policies is likely to be limited.

Trump’s first weeks have not left the 24-hour news cycle wanting. On the economic policy front, Trump’s tariff threats have generally been treated as the largest potential shock to the US, and even global, economy. We’ve written about the potential impact of tariffs under a variety of assumptions in our global outlook, and will soon provide an update on all the impact of the latest tariff threats. Bottom line, the tariffs will cause inflation in the US to rise, which will likely influence future Fed policy. However, at this point in time, tariff policy is still highly uncertain, both in terms of timing and ultimate magnitude, while there actually already is clarity on a number of policies due to the initial flurry of executive orders. Many of these, in particular on immigration and government hiring, impact the labour market. This piece therefore evaluates the potential impact of confirmed policy impacting the labour market, a rare signal in the sea of noise.

The reduction in the headcount of the federal government will increase the unemployment rate. Government has hired above its weight in the past year, supporting the labour market where most other sector’s total payrolls remained mostly flat. The new policies’ impact will be clearly visible in non-farm payrolls. A reduction in immigration, in conjunction with active deportation, will also increase the vacancy rate. The labour markets of sectors which rely more heavily on immigrant labour already tend to be tighter. There is a skill mismatch between the flow of unemployment coming from the government, and the sectors that already are, or are expected to be, tight. We estimate the effect of labour shortages on inflation to be limited, similar to the limited impact of widespread deportations under the Obama administration, despite markedly different conditions in the 2025 labour market compared to the early 2010s. Overall, these policies shift the Fed’s balance towards more rate cuts. The ultimate implementation of other policies, in particular tariffs, is likely to shift the balance in the other direction.

Trump’s new policies will stall labour force growth.

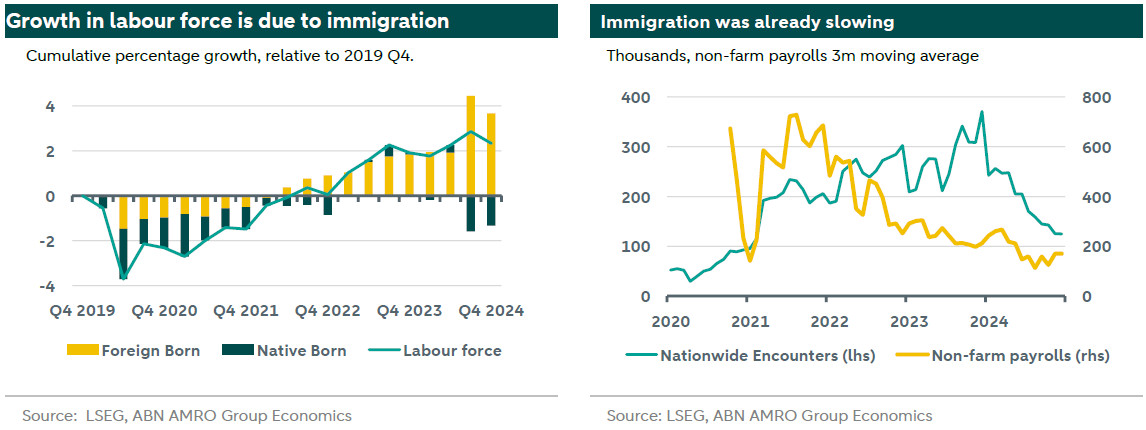

A variety of Trump’s Day 1 executive order focused on limiting immigration. He declared a national emergency at the southern border, enhanced the vetting process for visas, and generally increased the strictness of immigration laws. Since then, active deportation of illegal immigrants has started, although the numbers are low. Labour force growth has largely been driven by immigration, with any increase since the pandemic coming from increases in foreign born labour. Immigrants tend to be of working age, have a higher participation rate, and are therefore usually net positive contributors to the economy. Moreover, in the post-covid recovery, high levels of immigration were instrumental in sustaining labour force growth, supporting GDP growth, and importantly, limiting inflation pressures stemming from wages.

Even before the new policies, immigration was already slowing in tandem with weaker job growth.

Immigration was already slowing on the back of stricter immigration policy from the Biden administration, as well as weaker job prospects. The new policies are likely to lead to a further decrease in net immigration. After record highs in 2023 and especially the first half of 2024, the immigration flow is likely to decrease to levels seen at the end of Trump’s first term, with net immigration of maybe 0.5 million compared to more than 3 million in the last two years. It is clear that restricting immigration would have been more impactful in the hot labour market during the post-covid recovery. Back then, new labour was quickly absorbed, and indeed, dearly needed. The current timing is perhaps less harmful than it could’ve otherwise been, with slowing labour demand largely coinciding with the anticipated reduction in supply.

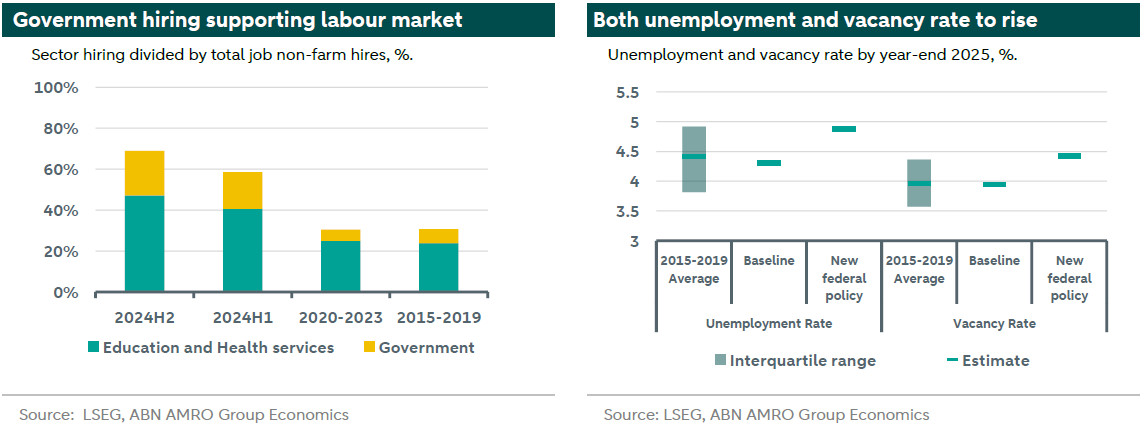

New federal hiring policies pull the rug out from under important labor market support.

Trump froze new hiring for civilian positions across the federal government and ordered federal agencies to terminate remote work arrangements. The latter is an active attempt to let workers resign. Return to office mandates have been shown to lead to increased turnover, and a new offer of 8-months pay for voluntary resignation is likely to amplify that effect. Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is likely to push for at least a 10% reduction in federal government staff, having fired 80% when acquiring X, and 10% at Tesla in April of last year. Over the past year, government has been one of the only sectors adding jobs. Putting this to zero, or even negative, would greatly alter the dynamics of the labour market. Had the government not hired last year, the average increase in non-farm payrolls would have been 129k rather than 167k. The starting point for the upcoming year is markedly weaker, and further DOGE ‘efficiency gains’ may impact government private contractors’ hiring as well.

Conservative assumptions on the reduction of the government workforce and immigration will increase both the unemployment and vacancy rate by 0.5%.

In the absence of the new immigration and government hiring policies, basic extrapolation of labour force developments and job creation suggests a minor uptick in the unemployment rate and minor decrease in the vacancy rate by year end. Both would still be close to their averages over the 2015-2019 period. In order to assess the impact of the administration’s new policies, we assume a conservative one-time 10% reduction in the federal workforce on the back of a Musk-type workforce reduction, and furthermore, an overall increase in turnover.[1] On the immigration front, the lack of immigration leads to an almost stable labour force, meaning new vacancies cannot be filled. This also slows the job creation process beyond the government. Research[2] on the impact of Obama-era deportations demonstrated that employment of native born workers also decreased. The mismatch between the newly unemployed from the government, and the increase in vacancies due to lack of immigrant workers, leads to sustained elevation of both the unemployment and vacancy rate. We expect both to increase by about half a percentage point compared to policy at the end of last year, pushing the rates to levels near the upper quartile of what we saw during 2015-2019. These figures do not assume any indirect or second round effects. For instance, further downside risk stems from immigrants failing to come into work for the fear of being deported, or more extensive cost-cutting at the government impacting suppliers.

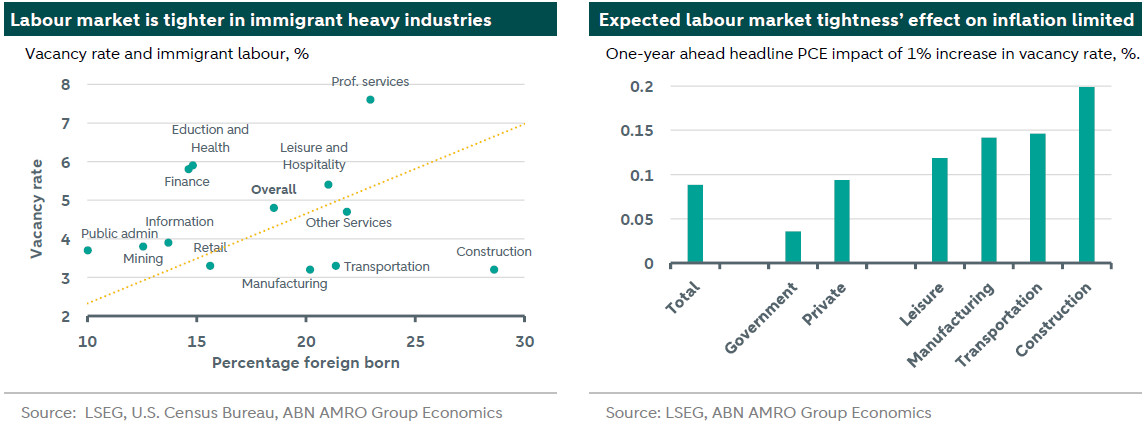

The vacancy rate is already elevated in immigration-dependent sectors.

The chart below plots the vacancy rate to the percentage of foreign born workers, to proxy their dependence on immigrant labour. Immigrant dependence is higher in construction, transportation, manufacturing and hospitality. Moreover, the vacancy rate is generally higher in sectors that have a higher percentage foreign born employees. Construction is a particular outlier with low vacancy due to generally low activity in the sector. This fuels the concern that a decrease in labour supply would lead to wage pressures, and ultimately end up in inflation. A notable absentee in the chart is the agricultural sector, which is also highly dependent on immigrant labor (roughly 20%), but the vacancy rate is not reported by the BLS. Mainstream media has widely reported on how a labour shortage in the agriculture sector might drive up food prices.

The impact of a reduction in immigration on inflation is likely mild.

A reduction in immigration is feared to increase inflation through at least two channels. The first, as highlighted above, is that a tighter labor market increases wages. The second is that unfilled positions could lead to lower production and therefore shortages in supply of goods. We estimate the effect of a tightening of the labour supply in various sectors on inflation, controlling for the broad macroeconomic environment[3], such as growth, inflation, unemployment, and measures of labour supply and demand. A supply-driven 1% increase in the overall vacancy rate – which has ranged between roughly 3.5 and 10% between 2000 and now, excluding the pandemic – has an upwards pressure of about 0.1 pp on headline inflation[4], but this headline effect is subject to substantial heterogeneity. The inflationary impact of tightness in immigrant dependent sectors is relatively large. The estimates in the chart standardized as a relative impact, meaning that tightness in construction is more than twice as inflationary as the overall average, with manufacturing and transportation about 1.5 times as inflationary. As an example, consider the scenario that the Trump administration reaches its goal of 1 million deportations this year. Under the assumption that these deportations are spread around sectors based on the current sectoral distribution of foreign born workers, the above estimates imply that inflation would increase by 0.15-0.20 pp.

Confirmed policies on immigration and government hiring bring significant downside risks to the US labour market, but limited upside risk to inflation. The mismatch in labour supply and demand makes both the unemployment and vacancy rate go up. These initial estimates add to the pre-Trump trend of a weakening labour market, and may lead to further amplification effects. Overall, they tilt the balance of Fed rate cuts to more easing. Upside risks to inflation are still elevated on the back of as-of-yet unknown tariff policies, and the relative magnitude of their impact is likely to tilt the balance of the Fed path to more restrictive territory again.

[1] We use turnover estimates, without replacement, consistent with academic estimates of increases in turnover due to return to office mandates. Based on estimates for S&P500 companies in Ding, Y., Jin, Z., Ma, M. S., Xing, B. B., & Yang, Y. J. (2024). Return to Office Mandates and Brain Drain. SSRN working paper 5031481.

[2] East, C. N., Hines, A. L., Luck, P., Mansour, H., & Velasquez, A. (2023). The labor market effects of immigration enforcement. Journal of Labor Economics, 41(4), 957-996.

[3] Formally we estimate a BVAR in building on e.g. Swanson, N. R., & Granger, C. W. (1997). Impulse response functions based on a causal approach to residual orthogonalization in vector autoregressions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92(437), 357-367.

[4] While, for instance, food inflation did rise substantially in the wake of Obama’s deportation policy, these can almost fully be attributed to global factors, rather than local supply constraints.