US - Resolving the labor market puzzle

This month’s labor data came in mixed. The establishment survey showed large job gains (272k) after a softer reading in April (165k). For the same month, the household survey showed a drop in employment of more than 400k, pushing the unemployment up to 4.0%, despite a decrease in participation. The fact that these two surveys point in different directions in any given month is not unprecedented; they disagree in one of every three months. The question is whether the trends of the two align, and the answer is a clear ‘no’.

While the establishment survey has shown a steady pace of job creation, the household survey displays a near horizontal development since 2023. For the year-to-date, the establishment survey claims creation of 1.2 million jobs, while the household survey saw a decrease of 100k jobs. Below we outline why we believe the job gains this year are closer to 90k per month, or 360k year-to-date. Our estimate implies a softer labor market than the non-farm payrolls from the establishment survey would suggest, but we still judge this to be consistent with a normalization in the labor market rather than raising alarm bells.

Bridging the labor data gap

In explaining the divergence, we start by looking at differences in sampling methodologies. The establishment survey samples more than 650k worksites, the household survey roughly 60k households. Both have a decreasing response rate, but the household survey is still at roughly 70%, while the establishment survey has dropped to 40%, raising concerns of potential sample bias. Both surveys rely on models to extrapolate their findings to the population. The household survey needs estimates of the overall population, while the establishment survey needs to estimate business births and deaths. This has become increasingly difficult since the pandemic, which uprooted old dynamics, and is a primary candidate for explaining the discrepancy.

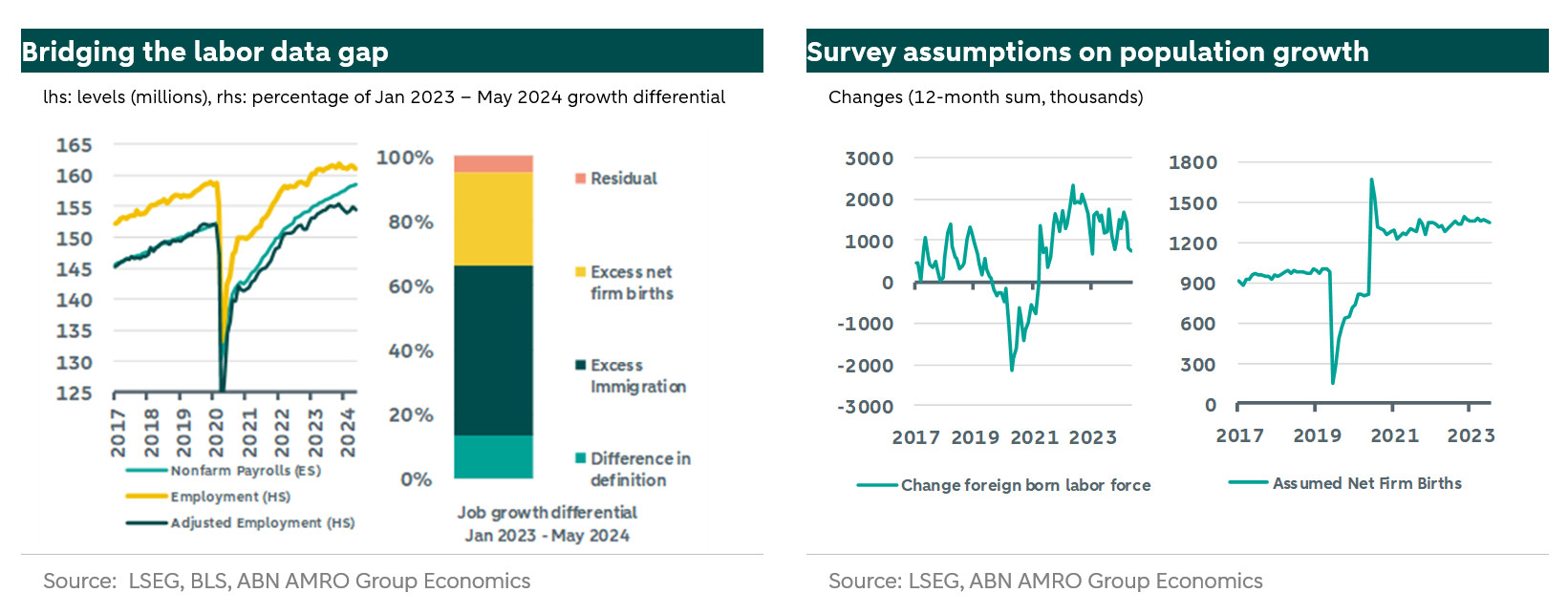

A first step in solving the discrepancy between the series is unifying their definition. Household includes the agriculture sector, while it is excluded from the non-farm payrolls in the establishment survey. Moreover, multiple job holders are counted multiple times in the establishment survey, and only a single time in the household survey. While the period since 2022 saw an increase in multiple job holders from 4.7 to 5.2% of total employed, the 5.2% is in line with pre-pandemic averages. Correcting for these differences in definition, the levels of the two series largely line up until 2022, but the series have diverged since. Still, the difference in definition accounts for about 375k of the growth gap between January 2023 and now.

What about the remaining divergence? We think this can be explained by two factors: 1) a likely underestimate of immigration the household survey, and 2) an overestimate of firm births and deaths of firms in the establishment survey. On the first point, estimating the post-pandemic population is tricky, but arguably the most important recent development has been the large inflow of foreign workers since 2021. A by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has revised the 2023 net immigration estimates up from 1.4 million to 3.3 million, and 2024 net immigration is likely to increase the population by another 3.3 million. Taking into account participation rates, these higher estimates of immigration bridge about two-thirds of the remaining differential in job growth since January 2023.

On the establishment side the assumed net births for firms has played a significant role, accounting for 2 out of the 4.25 million jobs created since January 2023. In normal times, these estimates should be close to the truth. At turning points, estimating firm births and deaths is far more difficult, even in the absence of the post-pandemic dynamics. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has assumed a structurally higher net birth rate compared to the pre-pandemic period, potentially a legacy of a temporary model used during the pandemic. If we rather assume a similar rate to the pre-pandemic period – a conservative assumption given recent rise in bankruptcy filings – job growth is adjusted downwards, accounting for nearly the remaining third.

Timing of data revisions is crucial

The above highlights that neither of the two series is likely to present an complete picture of the labor market. Ultimately, the household survey will be rebalanced at the end of the decade following a census, while the final revision of the establishment survey generally follows quicker, following final Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) data. Preliminary data suggests that jobs in 2023 may have been overstated by as much as a million. Final revisions of the period April 2023 to March 2024 will only be revealed early next year in the annual revision. For the data coming in now, we’ll have to wait until 2026. This summer, just before Jackson Hole, and importantly, the September FOMC meeting, the BLS will publish a preliminary release on the potential revision of 2023 data. If the strong revision we expect materializes, this will be a further motivation to start cutting rates in September.

The labor market is softer, but not weak

Where does this put us in evaluating the labor market? Considering the above, our best estimate is that payrolls in the establishment survey have grown closer to 160k per month since January 2023, significantly lower than the current BLS estimate of 250k. We expect a large part of the weakness to have been in the second half of 2023, continuing into this year. Indeed, year-to-date, we estimate growth of roughly 90k per month, versus the current BLS estimate of 247k. Conveniently, a similar conclusion is obtained, both in terms of growth rate and dynamics over time, using a roughly 40-60 weighting of the establishment and household survey employment statistics. This joint estimate shows a softer labor market than the nonfarm-payrolls would suggest, but with solid net job gains, it still does not paint an overly worrisome picture. During recessions since 1960, payrolls decreased by an average of 154k per month.

Finally, the above considerations on extrapolation from surveys to population are effectively absent in the computation of the unemployment rate as it cancels out in the numerator and denominator. It is therefore not impacted by uncertain dynamics in the evolution of the population of the labor force or firms. The uptick in the unemployment rate over the past few months is therefore the cleanest signal that the labor market is indeed cooling. This cooling so far remains consistent with a normalization in labor market conditions rather than something that should raise alarm bells, but given the lags with which monetary policy impacts the economy, the Fed will not want to wait for such alarm bells before it starts lowering rates. The cooling is therefore consistent with our view that the Fed will start cutting rates in September.