The strategic oil play

In an attempt to bring down oil prices, the US will lend out part of its strategic oil reserves in a coordinated action with countries such as China, India, the UK, South Korea and Japan. In the US, the pressure on President Joe Biden is high because many citizens/voters blame him for the, by American standards, very high price of petrol. In the US, lending out part of its strategic oil reserves. Whether lending out strategic oil reserves will have the desired effect remains to be seen. After all, in the first place, this group of countries can make strategic oil reserves available, but then it still has to be lent out before it actually comes onto the market. Secondly, the market will be watching for a counter-reaction from OPEC+. What this decision by the US and other oil importers does above all is to further inflame the relationship with OPEC+.

Draining strategic reserves

In an attempt to bring down oil prices, the US will lend out some of its strategicoil reserves in a coordinated move with countries such as China, India, the UK, South Korea and Japan. It is the fifth time that oil from strategic reserves has been used. The first time was during the Gulf War in 1991, the last time in 2011 due to the civil war in Libya. This time, 50 million barrels will come from the US strategic reserves. Of this, 32 million barrels will be made available in the form of a loan. 18 million barrels will be sold under the programme previously announced by Congress. The barrels will become available from mid-December. Besides the US action, India is making 5 million barrels available, China at least 7 million, Japan between 4 and 5 million, the UK 1.5 million and South Korea is yet to decide. All these countries are net importers of oil and are struggling with the consequences of 'relatively' high oil – and thus high gasoline – prices.

In the US, the pressure on President Joe Biden is building because many citizens/votersblame him for the, by American standards, very high price of petrol. Earlier requests to OPEC+ - the coalition of several OPEC members and other oil producers led by Russia - to increase production faster than planned were rejected. The OPEC+ members point to uncertainties in the market, such as falling demand due to new lockdowns, and their expectation that the supply/demand balance would improve in the first quarter of 2022 anyway. Nevertheless, the US and partners have joined forces and decided to lend out additional barrels of oil on a one-off basis in order to eliminate the current imbalance and allow oil prices to fall further.

Effects unknown, but probably temporary

Whether the lending of strategic oil reserves will have the desired effect remains to beseen. Of course, the increased supply of oil could lead to profit-taking on speculative positions. A temporary downward price movement was therefore to be expected but proved to be short-lived. Also on previous occasions when oil from strategic reserves was made available, the effect was mainly symbolic and temporary in nature. This time, too, the further effects are unclear for two main reasons.

First, although this group of countries can make strategic oil reserves available, itstill has to be lent out before it actually comes onto the market. Whether or not this supply will be used depends very much on the availability in refineries, for example. In addition, it is to be hoped that the strategic reserves do not disappear 1-to-1 into commercial inventories. In short, making these reserves available is not in itself a confirmation of actually using them.

Second, and probably more importantly, the market will be on the look-out for acounter-reaction from OPEC+. OPEC+ has so far always indicated that the market is moving towards a supply/demand balance in the first quarter of 2022, that there are too many uncertainties from the global demand side and that if any country is not recovering its oil supply towards the pre-COVID production level, it is the US.

Relations further strained

In terms of quantity, too, the US decision is easy to parry by OPEC+. Making 50-75 millionbarrels available is equivalent to about 1/2 of daily global consumption, or 3/4th if one takes the release of strategic reserves of the other consumers into account. Earlier, Biden asked OPEC+ to increase oil production by an additional 400,000 barrels per day (kb/d), on top of the already announced monthly increase of 400 kb/d. This one-off release of reserves is roughly equivalent to a one-time increase of 400 kb/d for a four-to-five-month period. In short, OPEC+ can easily parry this decision by skipping the 400 kb/d increase once or twice in the coming months. The effect would then be neutralized within a few months. OPEC+ will meet again on 2 December to discuss its production levels.

What this decision by the US and other oil importers does above all, is to further strainrelations with OPEC+. High energy prices, tightening climate policy, new talks with Iran on a nuclear deal, the tensions surrounding the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline between Russia and Germany, China's policy on energy-related commodities and the cool relationship between the US and Saudi Arabia mean that energy policy is now at the top of geopolitical agendas everywhere.

US oil production recovering only very slowly

If there is one country that has lagged behind in the recovery of oil production after thestart of the corona virus, it is the US itself. While oil production at the beginning of 2020 was still over 13 million barrels per day (mb/d), it stabilised for a long time at 11 mb/d. A slight increase is now noticeable, but at 11.4 mb/d, production is still nowhere near the level of two years ago. All the more striking is President Biden's call for more oil production while his local policy is more focused on meeting climate targets by 2050. In that context, he has, among other things, called off the construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline from Canada, announced stricter environmental measures and revoked permits for oil/gas production on federal land. Lower oil production has made the US a net importer again.

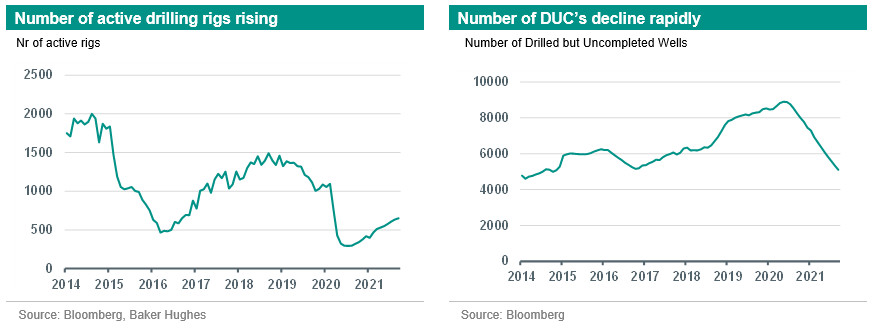

It is surprising that the graphs above show that the number of active drilling rigs isincreasing again, but production remains almost the same. In the past, there was always a lag of about six months before more drilling activity led to higher production, so based on historical patterns output should have risen more significantly by now. This shows that the relationship is now weaker. On top of this, we have seen a decline in the number of wells already 'drilled but not yet in production'. These Drilled but Uncompleted Wells, or DUCs, can be seen as the spare production capacity of the USA. Their number has almost halved in the last year. Many of these wells are dedicated to the production of shale oil. The characteristic of an average shale oil well is that the vast majority of production (70% on average) takes place in the first year of production. This means that one has to look for a new well quickly in order to keep production steady.

Slowly but surely, production growth is picking up again after the dip in March 2020.Recently, we read that production in one of the largest basins - Bakken - has even increased to a record level. At the same time, we see that access to financial markets for many oil products has become significantly more difficult in recent years. Furthermore, there is more discipline among these companies in terms of capital management. The larger producers, in particular, are looking more at a healthy business model and less at growth with borrowed money. Also, regulations and legislation (e.g. on waste water and methane emissions) have become stricter, labour costs have risen and permits are no longer granted on federal land. All these factors have increased the cost per barrel of oil, and are holding back growth in US oil production.

Nevertheless, there are signs that production will increase further next year. Thisproduction growth will come mainly from the smaller producers who are focusing on drilling the cheaper vertical wells. The International Energy Agency expects an increase to 11.8 mb/d. A growth that will help meet still-rising global demand. But also a development that will give little or no relief in the short term to the persistently high price of gasoline in the US and clashes with Biden's long-term climate policy. In the coming years, therefore, considerably more will have to be invested in oil production to prevent a rapid decline in US production levels. Especially now that the number of DUCs, the US spare production capacity, is rapidly decreasing. A development that is also seen outside the US. After all, investments in the oil sector do take place, but mainly in Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.