SustainaWeekly - The economic impact of extreme weather events

Extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, fires, droughts, flooding and tropical storms, are more commonplace and more intense. In this edition of the SustainaWeekly, we first start by setting out the channels through which extreme weather events have an impact on the economy. We then go on to summarise the highlights of our ESG Investor Survey, which were covered in much more extensive detail in an earlier publication. Finally, we focus on the emerging solar technologies, which could be game changers but are not yet commercially ready.

Economist: The economic impact of extreme weather events is different from chronic climate shocks. Chronic physical risk is gradual and deterministic. Extreme weather events are random and abrupt. Economic activity suffers in the immediate aftermath of an extreme weather event. The longer-term consequences on the economy depend on the capacity of the state to repair and rebuild and the prevalence of insurance contracts.

Strategist: We summarise the results of our ESG Investor Survey. Compared to last years’ survey, respondents place lower relevance to the EU Taxonomy compared to ICMA principles.More investors are allowed to invest in Sustainability-Linked Bonds, though many find points for improvement in this market. When evaluating ESG instruments, investors have a holistic approach, and more respondents now focus now on decarbonization strategies.

Sector: Solar power is a key renewable source for the energy transition. But it has three major challenges: efficiency, intermittency and materials use. The emerging solar technologies aim to tackle these challenges but they are not commercially ready. The emerging technologies that could be game changers are: perovskites, quantum dots, thermochromic photovoltaic glass and night solar. We take a closer look into these.

ESG in figures: In a regular section of our weekly, we present a chart book on some of the key indicators for ESG financing and the energy transition.

How to think of the economics of extreme weather events

The economic impact of extreme weather events is different from chronic climate shocks

Chronic physical risk is gradual and deterministic. Extreme weather events are random and abrupt.

Economic activity suffers in the immediate aftermath of an extreme weather event. The longer-term consequences on the economy depend on the capacity of the state to repair and rebuild and the prevalence of insurance contracts.

Introduction

The science is compelling – extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, fires, droughts, flooding and tropical storms, are more commonplace and more intense. These events are chaotic and disruptive and in important ways different from chronic physical shocks which tend to be gradual and to some extent also more predictable. We focus on extreme weather events in this note, and more specifically, on the channels through which these types of events have an impact on the economy.

The timing of extreme weather events

The link between anthropogenic activities and atmospheric CO2 concentration and temperature is unequivocal, as is the link between the earth’s temperature and the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. It should come as no surprise that the number of extreme weather events has risen in response to higher CO2 concentration levels and temperatures. In the EU, for example, the number of extreme events has doubled from just under 20 per year in 1980 to around 40 in 2021 according to analysis by the ECB.

Although research that links the frequency of extreme events with anthropogenic activity is well-established, scientists have only very recently started to establish a compelling link between any particular extreme weather event and anthropogenic activity. A good analogy to illustrate the difference in the causal link between anthropogenic activity and the frequency of extreme weather events on the one side, and anthropogenic activity and its link to a particular event is a coin toss. In a fair coin toss there is an equal chance of heads and tails. One side is more likely in an unfair coin toss, but we cannot say for sure that a particular outcome in an unfair coin toss is entirely the result of tampering with the coin. In the same way, we cannot say with certainty that a particular extreme weather event would not have occurred without climate change.

One important difference between physical chronic and acute therefore, relates to attribution. There is a clear and deterministic link between the emissions, GHG concentration, temperature and sea levels. That link is better established for the frequency and intensity of acute events than for any specific event.

Another difference relates to the occurrence of the event. Acute events will turn more frequent but they will remain random. By contrast, the chronic physical effects of climate change will emerge on a deterministic and gradual path. The difference is illustrated in the graphic below.

Transmission channel of extreme weather events

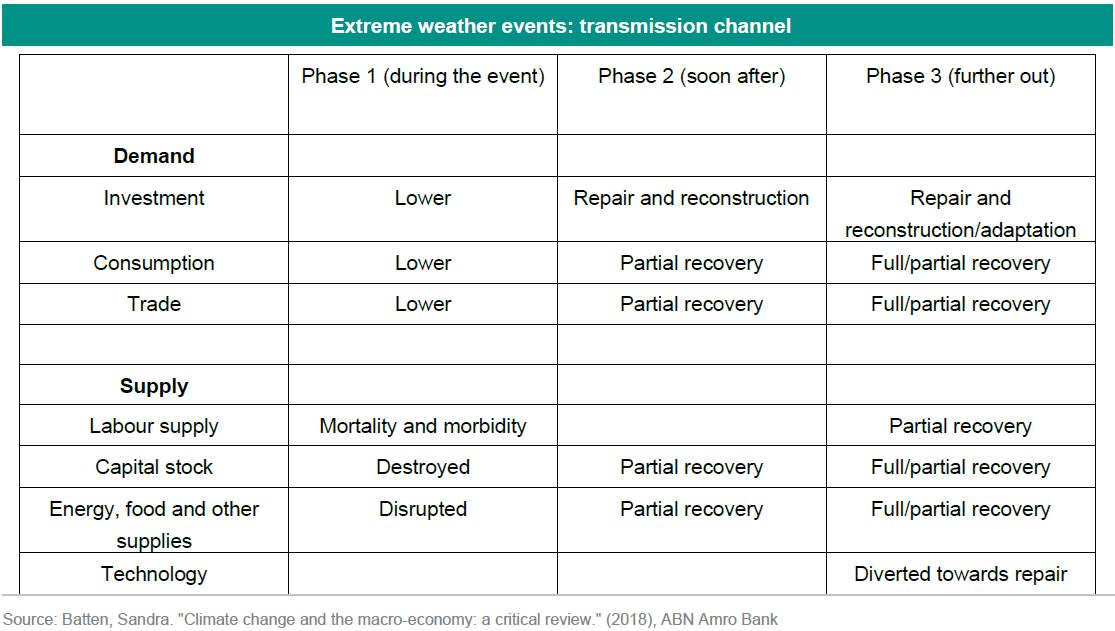

Having occurred, how does an extreme weather event impact the economy? A climate shock can have an impact on the demand and supply sides of the economy and in the case of an acute shock, the impact could vary over time. The table below lists a few demand and supply channels as examples and splits the impact into three distinct phases – short-term, medium-term and longer-term.

There is little disagreement that the short-term impact (Phase 1) of a climate event is negative for economic activity. The loss in household and business income and the destruction to wealth has a negative impact on consumption, investment and trade. Activity tends to recover in the period immediately after the event (Phase 2) as households and businesses look to repair and rebuild. The extent of the rebuild will depend on the (financial) resources available to the public and the private sector and the availability of labour and material. The economic impact further out is more diverse and will in large part depend on the extent of insurance coverage and public finances.

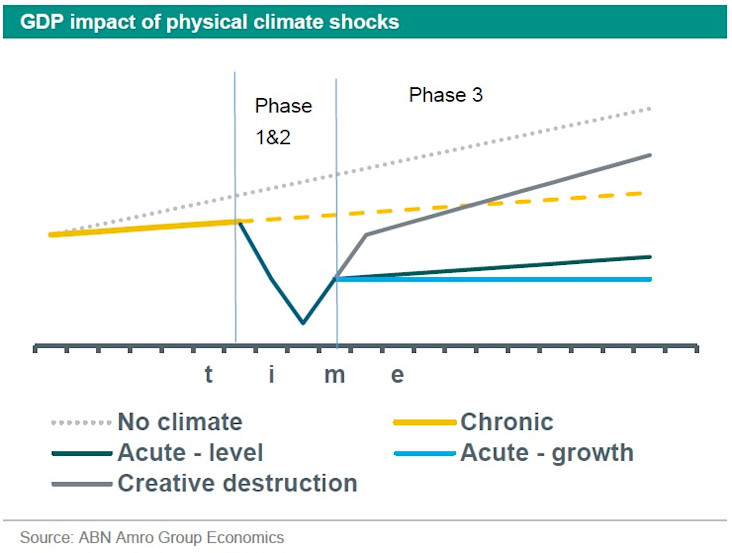

The chart above presents examples of possible outcomes. One possibility is that the economy is not able to recover to the pre-shock level of GDP in the foreseeable future. This could be because the credit conditions tighten and the government is unable to step-in with an effective reconstruction plan. The climate event would then have a scarring effect on economic growth (marked ‘Acute – growth’).

Another possibility is that the economy stages a partial recovery in the period immediately following the acute event (Phase 2) and economic growth recovers to its earlier trend. The climate event results a level shock to GDP (marked ‘Acute – level’).

A third possibility is where the damage from the climate event presents itself as an opportunity to replace existing capital stock with new and more productive capital stock. The recovery is not only immediate, but the improved capital stock results in faster economic growth (marked ‘Creative destruction’). While there is little evidence that shows that economic growth improves after an acute climate events, there are occurrences where income levels more than fully recover and this positive outcome is largely because of state intervention. 1)

There are other possibilities as well. For example, there may be sufficient resources in the near term for the economy to fully recover but trend growth could be lower as a result of increased indebtedness or tighter credit conditions and higher uncertainty.

1) Deryugina, T., Kawano, L. and Levitt, S., 2018. The economic impact of Hurricane Katrina on its victims: Evidence from individual tax returns. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(2), pp.202-233.