The counterfactual problem for carbon offsets

Carbon credit markets have been experiencing rapid growth driven by corporate net zero targets. However, recent studies raise questions about whether credits represent real carbon reduction. Two studies suggest that carbon reduction from Verra rainforest credits is being overstated. Verra strongly disputed these claims, with the modelling of the counterfactual being the heart of the discussion. There are initiatives in place to help strengthen credibility and growth of carbon credit markets.

Companies with voluntary carbon targets use the carbon credit markets to offset emissions they cannot eliminate, or at least not as quickly as necessary. The purchase of these certificates should complement the commitment to an ambitious internal decarbonization strategy, rather than being a substitute to one. The supply of credits mainly comes from various crediting mechanisms, with independent crediting mechanisms being the largest in size. Carbon credits represent quantities of greenhouse gases that have been kept out of the air or removed from it and include avoided deforestation, reforestation, avoidance or reduction of emissions and technology-based removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Voluntary carbon credits can also direct private financing to projects that reduce emissions that may not have happened otherwise.

Small but rapidly growing market

The market is still small but is growing rapidly, reflecting both rising prices and rising demand from corporate

buyers, on the back of growing net zero commitments, leading to higher volumes. According to the World Bank, the total value of the voluntary carbon market exceeded USD 1 bn by the end of 2021 and had already reached USD 1.4 bn by the middle of last year (see ). The Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (TSVCM) estimated that the market for carbon credits could be worth as much as USD 50 billion in 2030. The World Bank estimates that global average carbon credit prices moved from USD 2.49/tCO2e in 2020 to USD 3.82/tCO2e in 2021. Still, this is significantly below what for example the levels determined under the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS).

Growth in the carbon credit market is expected to be driven by accelerating demand due to rising net zero commitments by companies and increased supply of nature-based solutions and new technologies. Though a McKinsey report (see ) notes that the development of projects would have to ramp up at an unprecedented rate and the challenges in realising this could slow the growth in the voluntary carbon market.

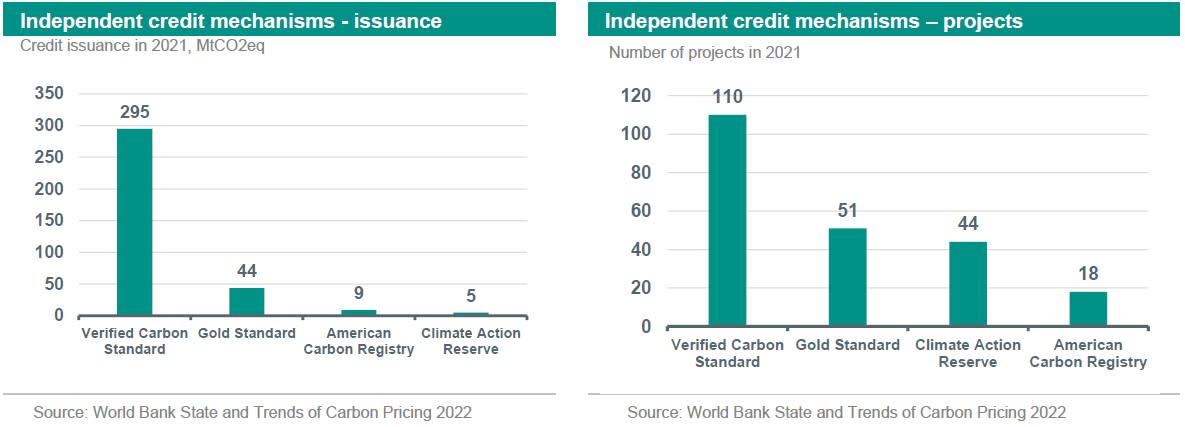

The carbon credit market is dominated by a small number of independent nongovernmental entities, which provide standards and crediting mechanisms (see charts above). Independent credit mechanisms account for three-quarters of issuers. Within this, the Verified Carbon Standard (Verra) is by far the largest in terms of credit issuance and the number of projects. However, as mentioned above, the size of this market is much smaller than compliance markets, such as emissions trading schemes (ETS). For instance, such schemes generated USD 56bn in revenue in 2021, dwarfing the numbers discussed above for carbon credit markets.

New research questions carbon offsets

As the World Bank notes, there remain significant debates about how to ensure the quality and integrity of carbon credits. The fundamental challenge is that the climate benefits from carbon credits can only be estimated against a counterfactual or reference scenario, which can obviously never be actually observed. Indeed, two recent studies have questioned the real carbon reduction in the projections that underpin some carbon credits. An investigation by the Guardian, Die Zeit and SourceMaterial (see ) claims that a significant percentage of Verra’s rainforest credits are ‘phantom credits that do not represent genuine carbon reductions’. This is strongly denied by Verra, which prides itself on ‘scientific rigor and transparency’, which has a process based on standard rules and requirements for each project, peer-reviewed accounting methodologies and with projects subject to independent auditing.

At the heart of the debate is the counterfactual. The investigation claims based on two studies from an international group of researchers that just eight of twenty-nice projects analysed showed ‘evidence of meaningful deforestation reductions’. Separately an analysis of 32 projects found that ‘baseline scenarios of forest loss appeared to be overstated by about 400%’. Verra has criticised the studies for using a ‘standardised approach’, which cannot measure the ‘unique local threats’ faced. In addition, it argues that ‘synthetic controls’ were employed, with the comparable areas used as a basis for deforestation measurement not reflecting pre-project conditions, but rather a hypothetical scenario rather than a real area (which is counter-denied by the researchers).

Furthermore, another important issue with carbon credits is that those are finite. There is only a certain amount that can be done to offset emissions, particularly when using natural removal techniques. This means that once deforestation measures have exhausted, or renewable energy capacity has increased, for example, companies are still left with emitting the same as they did before. This would not be a problem under a carbon offsetting mechanism using carbon removal and storage techniques. However, besides the fact that such technology is still in infant stages, such certificates would certainly not cost anything near the mere average of USD 3/ton.

Initiatives underway to help strengthen credibility of carbon offsets

The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market - an independent governance body for the voluntary carbon market – is working on scaling up the transactions for voluntary commitments by promoting high-quality credits and standardization of contracts to improve liquidity. It plans to set out this quarter its Core Carbon Principles (CCPs) and Assessment Framework (AF), which will set new threshold standards for high-quality carbon credits, provide guidance on how to apply the CCPs, and define which carbon-crediting programs and methodology types are CCP-eligible. This follows a public consultation that was launched in July of last year. Meanwhile, the World Wildlife Fund, the Öko-Institut, and the Environmental Defense Fund have launched the Carbon Credit Quality Initiative, which aims to deliver an interactive web application for scoring carbon credit quality.

Meanwhile, there are numerous other initiatives that set out specific rules on how carbon credits can be used for compliance by companies within a credible climate target framework. For instance, the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), has set out the Corporate Net Zero Standard, which specifies restricted scenarios in which the use

of carbon credits will be accepted for meeting net zero targets. The targets require ‘long-term deep decarbonization targets of 90-95% across all scopes before 2050. When a company reaches its net-zero target, only a very limited amount of residual emissions can be neutralised with high quality carbon removals, this will be no more than 5-10%’.

This article is part of the SustainaWeekly of 23 January 2023