SustainaWeekly - Europe reacts with green industrial strategy

In this edition of the SustainaWeekly, we first focus on the EU’s green industrial plan, which was launched at the summit at the end of last week. In this note, we set out the main features of the strategy, which is widely seen as a response to the climate subsidies in the US and China. We go on to assess the challenges caused by increasing electricity demand and some possible solutions to it. We wrap up this publication by taking a closer look at the disappearance of greeniums in automotive bonds and by analysing trend in ESG bank bond issuance and pricing at the start of this year.

Economist: The EU has set out a new green industrial strategy following a summit last week. The new plan is widely seen as a response to the climate subsidies in the US and China. The size of additional funding and subsidies is unclear but existing funding is significant. However, Europe’s regulatory environment is a break on the speed of the transition.

Sector: Challenges caused by increasing electricity demand cannot be solved in the conventional way. The growing share of renewable energy introduces the challenge of intermittency problems. Solving the supply-demand mismatch requires a range of flexibility solutions. Solutions are energy storage, expanding networks, and flexible demand.

Strategist: We have seen greeniums on bonds issued by VW and Mercedes Benz in the past. However, currently that the majority of these issuer’s green bonds strangely trade at a pick-up to the regular bonds. Although BEV sales at both issuers have not surged, the carbon reduction impact vs petrol and diesel cars should resonate in bond pricing as well.

ESG Bonds: Issuance of green, social, and sustainability bank bonds in euro rose in January by 174% compared to 2022, with covered bonds and senior non-preferred debt accounting for most of the increase. ESG bank bonds attracted larger demand than non-ESG peers, also resulting in lower new issue premia.

ESG in figures: In a regular section of our weekly, we present a chart book on some of the key indicators for ESG financing and the energy transition.

Europe’s green industrial plan

The EU has set out a new green industrial strategy following a summit at the end of last week

New plan is widely seen as a response to the climate subsidies in the US and China

The plan contains measures to improve four main areas: regulation; funding; skills and trade

The size of additional funding and subsidies that will emerge is unclear

Existing EU funding is significant and generally exceeds packages elsewhere

Europe’s regulatory environment is a break on the speed of the transition

The peculiarly named Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the US caused a stir in the corridors of power in Europe. The act, which was signed into law by President Biden in August, launched a USD 370bn support programme for green technologies. This sparked concern on the other side of the Atlantic that these incentives would see business and investment gravitate away from Europe and to the US. European officials also claim the tax credits, which are based on ‘domestic content’ requirements, are inconsistent with WTO rules. At the same time, China’s state support for industries – green and otherwise – is also a subject of great concern. Following a two-day summit at the end of last week, it seems that Europe has at least partially decided that ‘if you cannot beat them, join them’ as it has launched its own green industrial plan. In this note, we set out the main features of the plan.

Regulatory environment

Europe’s plan contains measures to improve four main areas: regulation; funding; skills and trade. Starting with the first pillar, the EU aims to achieve a ‘predictable, coherent and simplified regulatory environment’. The European Commission will put forward a Net Zero Industry Act, which would provide a simplified regulatory framework for production of products key for the energy transition, such as batteries, windmills, heat pumps and carbon capture and storage technologies. A key focus would be to reduce the length of permitting processes by setting time limits for different parts of the process and strengthening member states’ administrative capacity. It would also look to accelerate permitting procedures for net zero supply chain projects of strategic interest, use public procurement to encourage greener industry and promote European standards to help accelerate the roll-out of key technologies. Furthermore, the Commission will propose a Critical Raw Materials Act to ensure the security of supply of these materials by strengthening international engagement and via recycling. Finally, next month, the Commission will present a reform of electricity market design (more on this in a subsequent note).

Access to finance

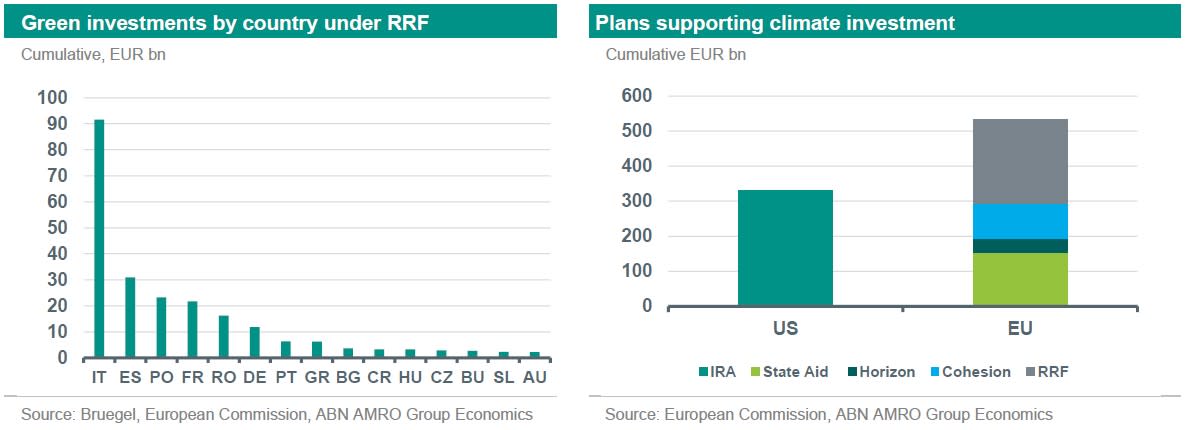

Large scale investment will be needed for the transition to net zero over the coming decades. Europe is concerned that ‘subsidies abroad are un levelling the playing field’ and that this calls for ‘access to funding for net zero industry to be extended and accelerated’. The Commission points out that available cumulative funding for green investment under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is already substantial. This is estimated by Bruegel at around EUR 240bn (see country breakdown in the chart on the next page on the right). Another EUR 100bn is available under Cohesion policies, and it is the intention to facilitate an accelerated mobilisation of these funds via standard reimbursement schemes for energy efficiency and renewable projects. Finally, EUR 40bn is available via Horizon Europe for green research and innovation.

The EU intends to allow further flexibility for member states to grant state aid limited to ‘carefully defined areas and on a temporary basis’ up until 2025. This follows upon the existing state aid space to deal with the fall-out from the energy crisis. Indeed, the Temporary Crisis Framework (TCF) will now become the Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework (TCTF). The latest version would extend provisions to all renewable technologies, hydrogen and biofuel storage. Importantly, it allowed the ‘possibility of granting higher aid to match the aid received for similar projects by competitors located outside of the EU’ for strategic net zero sectors and technologies, including via tax benefits.

While the Commission hints at the need for additional EU level funding to supplement state support, heads of state decided to focus on the use of existing funds. One concern is that individual member states have varying capabilities to provide national support. On the other hand, the RRF is skewed towards countries who may have weaker capabilities, and those funds can be repurposed to this end. The size of additional funding and subsidies that will emerge is unclear. Last year, the Commission approved green aid schemes worth EUR 51bn for the EU as a whole. One might expect this amount to be at least matched annually given the new initiatives.

Enhancing skills

The energy transition will lead to a sharp increase in demand for labour with new skills across a wide number of areas. We have noted before on previous publications, that the labour market for transition jobs is much tighter than the overall labour market. The EC notes that the transition will therefore require ‘large-scale up-skilling and re-skilling of the workforce’. A plethora of schemes is already available to support this process, while the Commission is proposing a number of additional programmes. For instance, targets and indicators will be developed to monitor the supply of and demand for transition jobs, while a number of schemes will be set up to facilitate the training of professionals in various green sectors. The European Social Fund (EUR 5.8bn), Just Transition Mechanism (EUR 3bn) and RRF (EUR 1.5bn) are already providing funding for enhancing green skills, though significant new funds do not appear to be in the offing.

Global co-operation and trade

The final pilar of the plan involves ‘global cooperation and making trade work for the clean transition’. The idea behind this is net zero can be best achieved if the incentives for green investment is underpinned by the ‘principles of open trade and competition’. The Commission proposes the establishment of a Critical Raw Materials club to bring together the consumers of these materials with resource-rich countries; industrial partnerships to promote the adoption of net zero technologies globally and an export credit strategy focused on green sectors.

However, at the heart of this pillar is to defend the EU from unfair trade practices like ‘dumping and distortive subsidies’ using trade defence instruments. The plan also points to the new Regulation on Foreign Subsidies, which became active at the start of the year. It aims to help investigate subsidies granted by third countries. Remarks by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen at the summit made this clear. She asserted that China is ‘giving massive subsidies’ so the topic is much wider’ than the IRA and that the EU was developing ‘a much broader strategy to deal with that’.

Funding is significant, regulatory environment is a problem

Investment levels still fall short of what is needed for a net zero scenario. Having said that, the size of the EU schemes compare favourably with those in the US plan. For instance, taking together all the elements set out above, and assuming that national state aid continues at the 2022 level through 2025, the EU funding exceeds that in the IRA. However, the mix in the US is more skewed towards subsidies and tax credits, and in the EU more towards direct investment. Perhaps the biggest issue tackled in this plan in this regulatory environment. For instance, studies show that the planning and permitting duration for wind projects is much higher in most EU countries compared to the US and China (although there are ongoing efforts at EU level to change that). Similar barriers exist for other renewable projects as well as accessing funds. So the focus on improving the environment is positive, however it remains to be seen whether best practice spreads.