SustainaWeekly - ETS reforms to result in adoption of more expensive technologies

In this edition of the SustainaWeekly, we first look at how ETS reforms may impact the price of emission allowances. We then provide estimates of marginal abatement costs of various decarbonization technologies and what carbon price would be needed to make them economical. We then go on to present a sneak preview of internal investor ESG scores provided by ValueCo, focusing on the assessments for European Globally Systemic Important Banks (GSIB’s). A more comprehensive note will follow as part of our ESG Strategist publication series. Finally, we zoom into solar power focusing on current trends in Europe and globally, its role in the transition and the challenges facing this technology currently and in the future.

Economist: The EU ETS sits at the heart of EU decarbonisation plans. The ETS is expanding in scope and turning more stringent. The overall supply of allowances is set to fall and at the same time demand for allowances is expected to rise. The ETS allowance price is likely to rise as a result, which in turn will encourage wider adoption of technologies, such as carbon capture and storage.

Strategist: We have entered a research partnership with ValueCo with the aim of providing additional insights and analysis on ESG to our clients. ValueCo gathers the internal ESG scores assigned by investors and harmonizes them for comparability. We show the latest ESG opinions and consensus score amongst a range of European GSIB’s, though a more comprehensive note will follow as part of our ESG Strategist publication series.

Sectors: Solar power is the fastest growing among all renewables. However, capacity could slow down the roll out of solar power and limit its potential. Cannibalization in renewables could trigger a lower capture rate, which in turn could lead to a slower deployment rate for solar panels. Securing supply chains for solar panels are essential to achieve Europe’s targets for solar power.

ESG in figures: In a regular section of our weekly, we present a chart book on some of the key indicators for ESG financing and the energy transition.

ETS reforms to result in adoption of more expensive technologies

The EU ETS sits at the heart of EU decarbonisation plans. The ETS is expanding in scope and turning more stringent.

The overall supply of allowances is set to fall and at the same time demand for allowances is expected to rise

The ETS allowance price is likely to rise as a result, which in turn will encourage wider adoption of technologies such as carbon capture and storage

Introduction

The EU has set for itself an ambitious target of reducing net GHG emissions by 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels. This is an intermediate target enroute to the final objective, which is climate neutrality in the EU by 2050. The Emission Trading System (ETS) is a key instrument of abatement in the EU. The ETS covers around 40% of total EU emissions and is also one of the biggest and most well-established emission trading markets in the world. In this note we outline important changes that are afoot for the ETS and the implications of those changes for the ETS price.

Emissions Trading Scheme

The EU ETS is a trading system that is designed to reduce GHG emissions by setting a price on those emissions. The EU ETS works on a 'cap and trade' principle. A is set on the total amount of GHG that can be emitted by the operators covered by the system. The cap corresponds to the total amount of permits issued. Member states auction their allowances and participating companies must buy these tradeable allowances to compensate for the GHG that they emit. The price of the permit is set in the ETS market. By internalising the cost of emissions, the ETS encourages participating firms to invest in emission reduction technologies. The system is also designed to achieve emission reduction at the lowest cost to industry.

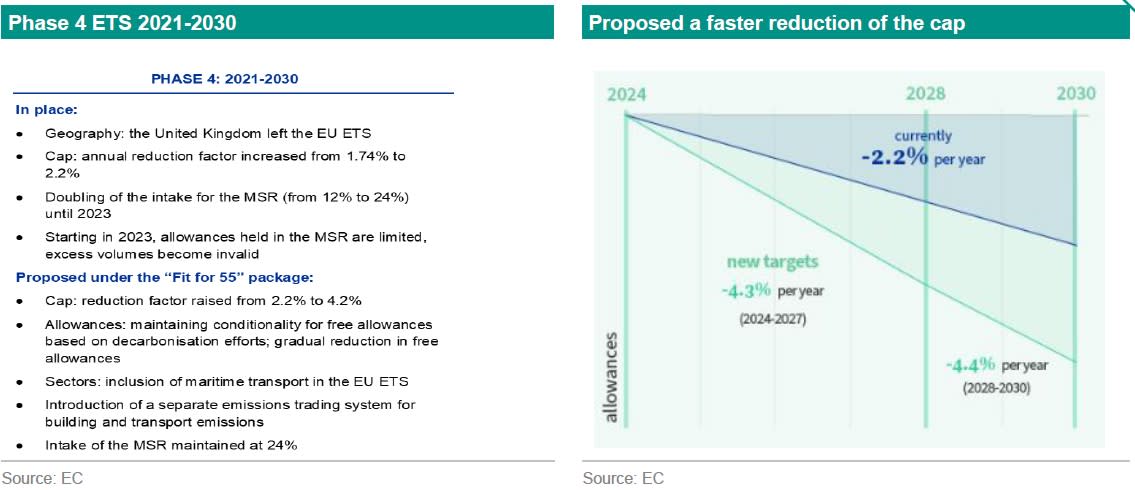

The ETS will undergo important reforms over the next few years. The overarching objective of the reforms is to reduce GHG emissions for ETS sectors by 62% by 2030 (source: ). This will be gradually reducing the cap on emissions and the associated permits in circulation.

To begin with, there will be a one-off reduction of the overall emissions cap by 117 million allowances (re-basing) phased over two years: 90 million will be removed in 2024 and 27 million in 2026. To place this in context, the total amount of allowances was 1,134,794,738 in May 2023. Every allowance corresponds to 1 ton of CO2 emissions. Auction volumes from 1 September 2023 to 31 August 2024 will be reduced by 272,350,737 allowances, which will be placed in the Market Stability Reserve (MSR). The Market Stability Reserve aims to provide stability to the EU Emissions Trading System.

Taken together, these new allowances will be accompanied by a steeper annual reduction factor of 4.2% until 2027 and to 4.4% from 2028-2030. This is double the speed of the existing 2.2% target (see chart below). These reform measures will together lower the supply of ETS permits and act to raise the price of the permit.

Another important change is the withdrawal of free allowances to ETS industries. Free allowances will be phased out from 2026 to 2034 and in particular from 2028 onwards. Removing free allowances will increase the demand for permits and increase their price.

The ETS is also expanding in scope with the inclusion of the maritime transport sector. The maritime sector accounts for around 2% of global emissions and is widely considered, along with aviation which, as it happens, is already included in the ETS, as one of the hardest sectors to decarbonise. The maritime sector will be phased into the EU ETS from 2024 to 2026.

In addition, the EU will create a new and separate ETS known as ETS II for the building and road transport to complement the existing ETS. ETS II will be operate from 2027. The EU ETS will put a price on the fuel that will be used in the building and transport sectors. An emission reduction cap of 42% by 2030 compared with 2005 levels is set for ETS II. A separate price stability mechanism will be set-up for this new market which will kick-in when the ETS price rises above 45 Euros.

What is the role of marginal abatement costs of decarbonization technologies?

The price of emissions set on EU ETS reflects the balance between supply of permits (or emission allowances) and the demand for these permits which is driven the total amount of GHG emissions. As discussed above, the supply of permits is on a pre-determined glide path which is set to steepen (see chart above). The demand for permits is however, unknown. It will depend on the economic growth generally, but more specifically, on the demand for the products and services covered by the sectors included in the ETS scheme.

Demand will also depend on the cost of abatement which is heavily influenced by technological developments. In practical terms it means that the abatement cost for a technology to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is the total additional costs, i.e. investment costs plus the difference in operating costs, divided by the avoided emissions.

The abatement price ranges from negative values to many hundred euros for hard to decarbonise sectors and technologies. A good example of negative abatement costs is LED lights that are operated by a motion sensor. In this case, the gains from energy cost saving outweigh the investment. More difficult sectors include aviation and shipping where existing technologies are currently prohibitively expensive and in case of shipping the future energy carrier is not yet decided.

The marginal abatement cost curve (MACC) summarises the cost of abatement for technologies. More specifically, the MACC represents the incremental cost of reducing one additional tonne of emissions/pollution. The MACC varies across countries and evolves over time. For example, heat pumps are an attractive alternative to a gas boiler in countries where the cost of electricity is low relative to the price of gas. These costs will also evolve over time in line with technological developments and the fiscal regime that is in place. Put differently, a MACC curve represents a point in time estimate of the abatement cost for different technologies in a particular county or region.

What are the marginal abatement costs for the 11 crucial technologies?

In our Sustainaweekly of 3 April we defined eleven technologies/group of technologies that help to decarbonize the world by 2050. These are: lithium-ion batteries, heat pumps, permanent magnets, electrolysis & fuel cells, photovoltaics, concentrated solar power, wind energy using aerodynamic force, technologies that produce synthetic fuels, carbon capture and storage and combined heat and power and digital technologies. Complete decarbonisation will require the adoption of most, if not all, these technologies.

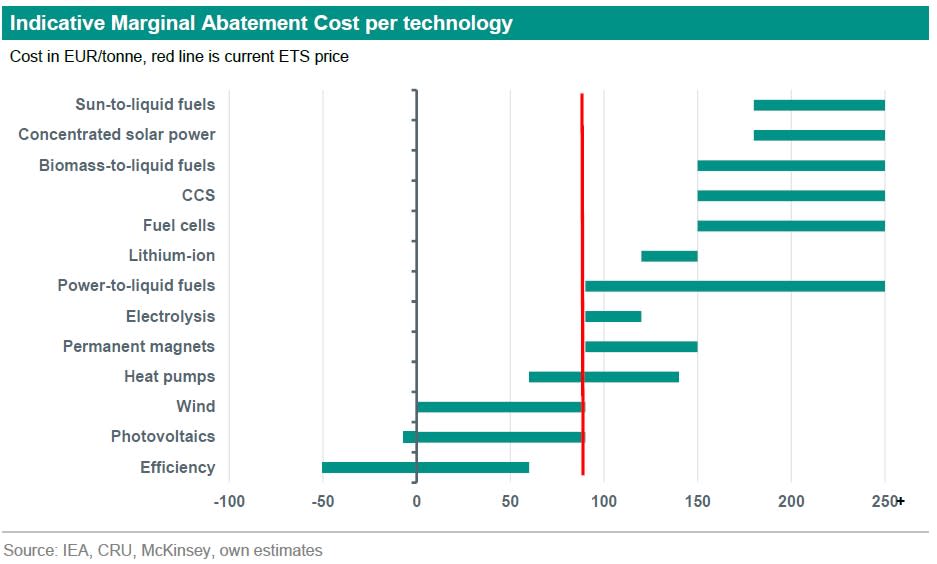

We summarise the pecking order of each of these technologies based on an estimate of the cost of removing one tonne of carbon. Our stylised MACC starts with least cost options, such as efficiency gains, at the bottom of the graph below, followed by solar and wind. These technologies are widely adopted and profitable at the current ETS price. Next in line is heat pumps which sits on the 90 Euro current ETS price. The other technologies on right side of the red line are not yet profitable but will come into play if, as we expect, the ETS price rises in response to the reforms discussed previously.

As seen in the figure below, there are three types of synthetic fuels (see more on these fuels in our ESG Economist – No easy road to decarbonizing road mobility). They are:

Biomass-to-liquid produces biofuels (any fuel that is derived from biomass) such as renewable diesel/hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO)

Power-to-liquid produces e-fuels such as e-methane, e-kerosine and e-methanol

Sun-to-liquid produces solar fuels such as hydrogen, ammonia

The technology to manufacture these fuels varies along with the price. Most of the technologies to produce synthetic fuels for aviation and shipping are in the expensive territory.

What is the impact of the marginal abatement costs on ETS prices?

With an ETS price currently around EUR 90 per tonne CO2, the majority of decarbonisation technologies are more expensive than the ETS price. Only efficiency measures, wind to replace coal and gas and solar to replace coal power are attractive to invest in which involves small scale and large scale power generation. In order to invest more in the other decarbonization technologies, the marginal abatement costs for these technologies need to decline or the ETS price need to increase or a combination of both.

Based on current state of technological developments, the maritime sector will likely buy allowances until a clear technology emerges for the future energy carrier, resulting in upward pressure on the ETS price. The higher ETS will nevertheless serve as an important first signal for the sector to decarbonise. The higher ETS price will however, encourage the widespread adoption of other less-hard-to-decarbonise technologies such as carbon capture and storage. In other words, by lowering the cap and by introducing hard-to-decarbonise sectors, the ETS will incrementally bring into play less expensive technologies that are currently too expensive relative to a carbon price at 90 euros.

To sum up, the EU ETS will continue to play a central role in setting an emission price that will encourage the market to adopt the most cost effective transition technologies. Reforms to the ETS will result in a wider gap between demand and supply and that in turn will raise the price of emissions and bring into play technologies such as carbon capture and storage. As the MACC suggests, the ETS price alone is not sufficient for decarbonisation. Complementary measures, such as targets for emission efficiency and outright bans on certain technologies such as ICE for passenger cars, will be necessary to achieve overall climate neutrality.