SustainaWeekly - Energy improvements can alleviate the pain for Dutch landlords

Rental prices for housing in the unregulated sector have risen dramatically in recent years, specifically in the major Dutch cities. The now outgoing minister of public housing has had a law in the works for some time, called the Affordable Rent Act, which includes a rent ceiling for what today still qualifies as unregulated rentals. In this week’s SustainaWeekly, we outline the consequences for housing investors of the potential law, by assuming a theoretical investment with energy renovation based on a property that would fall into the regulated segment based on the proposed law. Our next note covers the main aspects of EU-ETS II such as the phase in process, associated mechanisms, and potential dynamics and impacts. In our final note, we focus on report from the European Banking Authority (EBA) about the appropriateness and feasibility of including ESG factors in the current prudential framework, and the Pillar 1 Framework in particular.

Co-author: Bram Vendel

Strategist: The yet-to-be-approved Affordable Rent Act has triggered concerns among investors in Dutch residential real estate due to rent cuts and rent regulation. Housing owned by small investors often still has a poor energy label. We show that a boost in EPC label allows for the property to escape upcoming rent regulation, while the renovation investment is not alarmingly high. The investor return after renovation would remain acceptable.

Economist: EU-ETS 2 is a new separate cap and trade scheme that covers emissions from road transport, the built environment and industrial sectors that are not covered under EU-ETS. The system envisions a gradual phase in with emission reporting and monitoring starting in 2025 and 2027 as a first compliance year. It is important to analyse the impacts of EU-ETS II in combination with other climate policies to achieve an efficient transition.

Policy & Regulation: The EBA published a report about the appropriateness and feasibility of including ESG factors in the current prudential framework. The regulator notes that there are still challenges regarding ESG data, for instance, the lack of a common, standardized and complete classification system. At this stage, the EBA does not recommend introducing environmental-related adjustment factors in the calculation of banks’ capital requirements.

ESG in figures: In a regular section of our weekly, we present a chart book on some of the key indicators for ESG financing and the energy transition.

EPC improvement can alleviate the pain for Dutch landlords

The yet-to-be-approved Affordable Rent Act has triggered concerns among investors in Dutch residential real estate due to rent cuts and rent regulation

Housing owned by small investors often still has a poor energy label

We show that a boost in EPC label allows for the property to escape upcoming rent regulation, while the renovation investment is not alarmingly high

The investor return after renovation would remain at an acceptable level

Rental prices for housing in the unregulated sector have risen dramatically in recent years, specifically in the major Dutch cities. This affects the affordability of housing for households with average income, and as such the government feels compelled to intervene in the market. The now outgoing minister of public housing has had a law in the works for some time, called the Affordable Rent Act, which includes a rent ceiling for what today still qualifies as unregulated rentals. Private property investors, who are already facing a much higher transfer tax, are concerned by this measure as it implies a further erosion of returns. However, the law also gives opportunities to still operate the property in the ‘free sector’ when a property has a sufficiently high EPC label.

The law is yet to be approved, while the Netherlands has elections upcoming and some political parties leading the polls have already hinted at their disapproval of this law. Nevertheless, there is a chance that the law will still be passed and in this article we outline the consequences for housing investors, by assuming a theoretical investment with energy renovation based on a property that would fall into the regulated segment based on the proposal law.

What does the law entail?

The rent law aims to create a new category of regulated middle-rent that, as in the social/low income segment, determines the rent based on the home value points system (WWS). Under the WWS, points are attributed to a property based on characteristics such as area, number of individual rooms, furnishing, the fiscal value (called WOZ), as well as the energy label. A property which has less than 145 points currently qualifies under social rent with a rent ceiling of EUR 808 per calendar month. The new law envisages that properties scoring between 145 and 187 points will also be subject to a rent ceiling, albeit a higher cap of EUR 1,100 per calendar month. In many cases, this would result in a rent cut, since these properties are currently let in the unregulated space. Existing rents on these properties will not change, however at a new lease the landlord is obliged to adjust the price to the new ceiling. Furthermore, the landlord can only increase the rent annually by the CAO wage outcome plus 0.5%. A slight exception in rent growth is made for new construction falling in the middle-rent segment where an annual rent increase of up to 5% can be implemented under certain conditions. The measures will remain in place until the availability of affordable rental housing is deemed sufficient by the government, which seems subjective.

Based on a possible rent cut at the point of a new lease and the already applicable measures of higher transfer and income tax, it seems that the measures combined will lead to a huge deterioration in rental yields for landlords. However, calculation tools (such as those of the Rent Commission but also of the central government itself, see and ) show that a strong EPC label could keep the property in the unregulated segment and therefore not subject to rent control. Before showing such a sample calculation, let us first reflect on the importance of the energy label in Dutch lettings.

Small tenants usually own bad EPC label properties

Energy labels are becoming increasingly important in the Dutch housing market. Since the energy crisis, buyers and tenants increasingly take into account the energy efficiency of a home in their purchase decision. The energy label provides a proxy for expected energy consumption and cost. Under a poor energy label, the costs can rise sharply, making the purchase or the letting unattractive. Finally, the decision to opt for a strong EPC label is increasingly driven by environmental objectives.

The registration of EPC labels is also playing an increasingly important role in the purchase and rental market. Only 44% of owner-occupied homes have a label, while the percentage for rental homes is over 70%. Rented homes are required by law to have a final energy label when rented out. Owner-occupied homes do not have this obligation and are only required to have a label upon a sale of the property. Also, with owner-occupied homes, besides the well-known mortgage rate discount on A and B labels, there are few incentives to have a label registered and the percentage of final labels is therefore much lower.

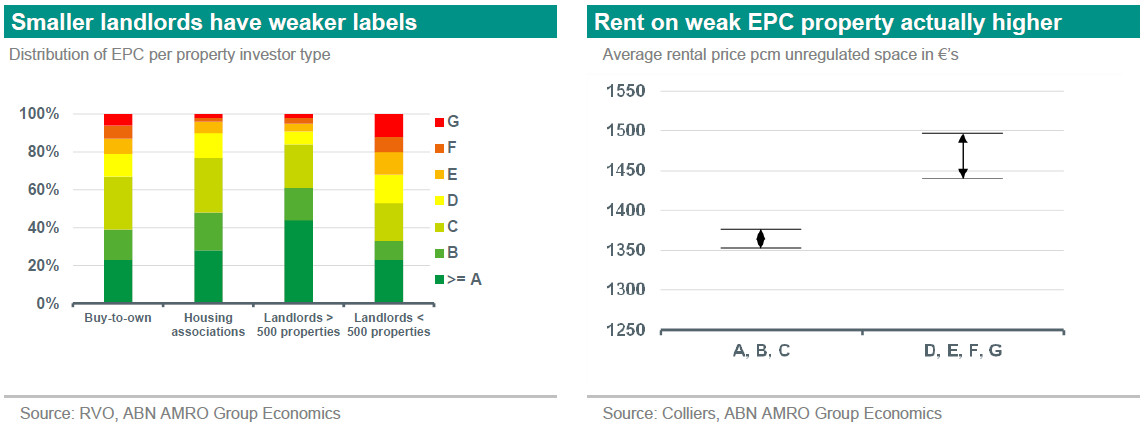

Also, the distribution of energy labels differs greatly between owner-occupied and rented homes and even more so within the rental market. In general, rented properties have on average a better label than owner-occupied homes. This is mainly properties of social housing associations and lettings by large (institutional) landlords. In the latter group, a whopping 84% of homes have a C label or better. In contrast, landlords with less than 500 homes have a much weaker label distribution. Only 53% of what is rented has label C or higher, compared with 69% for the total housing stock. Small landlords therefore face a major sustainability challenge or transition risk.

Strong EPC label does not imply a higher rent

A more sustainable property requires an upfront investment but that then leads to savings in energy costs over time. However, this does not immediately result in a higher rent. Often the opposite is true, and lettings with a poor label are generally more expensive, as shown in the right hand chart above. This is because better EPC label properties tend to be larger in size and therefore cost less per square metre. Many pre-war Dutch rental properties have low energy labels (such as F or G) and are typically small in size. In addition, a large proportion of these homes are in the larger Dutch cities and Amsterdam accounts for as much as 30% of total F and G home population. Higher rents therefore are mostly driven by location.

Given that the energy efficiency investment does not translate into higher rents, small landlords lack the incentive to make their portfolio more sustainable. This causes the average energy label of this group of landlords to lag significantly behind the rest of the market. The graph above also shows that the current rent in energy inefficient homes (D, E, F, G) is significantly above the proposed rent ceiling of 1,100 euros, and these could be facing a rent cut. An EPC label boost could keep them in the unregulated space and avoid a rent cut.

An upgrade from a G to B label results in 45 extra WWS points

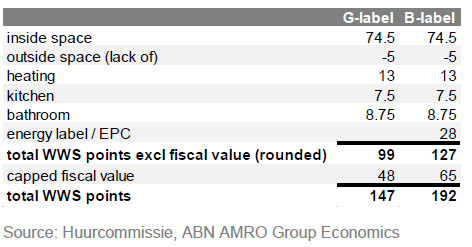

The energy label plays an important role in determining the points that are needed to check whether a rental falls in the regulated or unregulated space. Through a calculation tool available on the Dutch Rent Commission website (see ), one can check for the potential number of points that can be assigned to such a property, after entering all kinds of relevant property data. We apply the tool to a hypothetical apartment of 70 square meters in Amsterdam with a fiscal value of EUR 500,000. Furthermore, the property has no outdoor space, a simple kitchen & bathroom furnishing, a small storage area and central heating in all rooms by means of a boiler. The table below shows the difference in WWS points when this property has a G label or a B label. The G-label property at 147 points qualifies for the new regulated mid-rent segment, while the B-label property with 192 points should be able to stay in the unregulated segment (remember, the threshold was 187 WWS points).

The table also shows that a capped fiscal value contribution is applied, since otherwise the currently high property price level in especially larger cities would give a significant boost in the number of WWS points. Hence, the fiscal value contribution to the number of WWS points can never exceed 33.3% of the total. When we hypothetically scrap this cap, the number of WWS points would have been 19 points higher in the case of the G-label, for example. This is currently unregulated, but would soon qualify as also middle-rent. On the other hand, due to a stronger number of points excluding the fiscal value contribution assigned to the B-label house, the effect of capping is also weakened and it only makes a difference of two points if the fiscal had been fully included (so with uncapped fiscal, the point count on the B-label property would be 194).

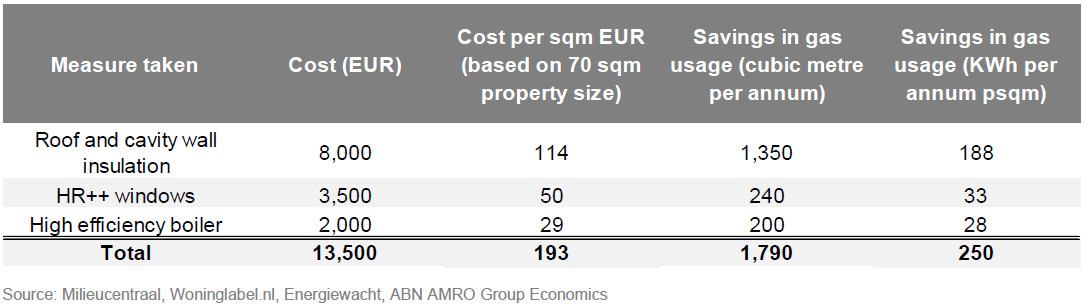

What is required to go from a G- to a B-label?

The example above shows a clear difference in the number of WWS points between a G- and B-label house. Still, the investment required to get this done must be profitable for a landlord, taking into consideration the ability to avoid future rent reductions. We show that relatively simple solutions aimed primarily at energy savings, including insulation, we arrive at an expenditure of 193 Euros per square meter of living space and a saving of 250 KWh per square meter per annum, as shown in the table on the next page. Given that the consumption per square meter per year of a G-label house is over 380 KWh, while a B-label house consumes only 190 KWh, the intended measures could indeed bring about the desired jump in label and avoidance of the middle-rent regime.

A 5.8% property return is not large…

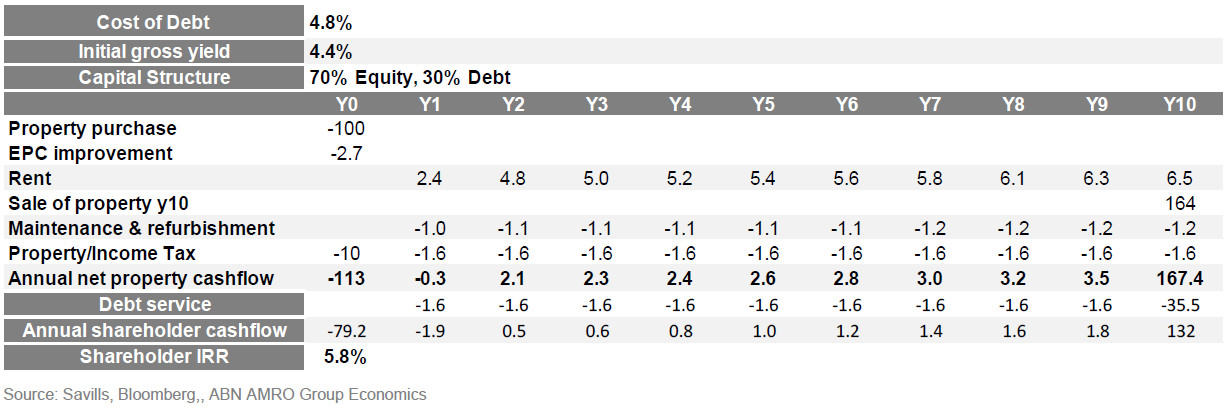

We now have sufficient data to calculate a theoretical 10-year investment in our previously mentioned Amsterdam home, migrating from a G-label to a B-label through the above measures. We describe the various inputs for our return calculations below:

Financing structure: given the current high cost of debt, we apply a conservative capital structure of 30% debt and 70% equity. The entire debt is repaid at the end of the investment horizon. In terms of interest rate we take the current market rate on a public bond issued by Vesteda, a conservatively financed fund that invests purely in Dutch residential properties.

Gross initial yield is 4.4 percent based on Colliers' latest report on the state of Dutch commercial real estate

A 5% annual rental growth rate seems a reasonable assumption and we suspend rent in year 1 for 6 months due to renovation

Sale of the property in year 10 goes at a higher exit yield of 4% than at inception due to our expectations for interest rate declines starting next year

A renovation from a G- to a B-label is, as shown above, 193 euros per square meter or 2.7% of the total house price

Maintenance expense is conservatively estimated at a total expenditure of 20% of the purchase price spread over 20 years and this is on top of the investments related to energy savings. Maintenance costs increase by 2% per year due to inflation.

Transfer tax at inception is 10.4% of purchase price. Income tax equals 32% on a 6% flat rate return (after deduction of cost of debt).

In the financing table on the next page we have summarized the above input variables, which will also serve as the basis of our return calculation. We base everything on a 100 EUR investment with the other variables (where necessary) normalized to this 100 EUR investment using current market parameters such as initial yield in percent and energy renovation costs per square meter. After deducting interest and repayment of debt, the investor retains an annual net cash flow that serves as the basis for its return on equity. This amounts to an annual total return of 5.8%. In comparison, the return becomes heavily negative if the property falls into the mid-rent segment by maintaining the G-label due to the rental discount of around 45%.

..., but it may still entice the long-term investor

Obviously a 5.8% expected return could be deemed slim for an equity investment and it is only 100 basis points higher than what the lender of debt can achieve on this project. However, especially given our conservative assumptions and a prospect of lower base rates next year, this still seems like a reasonable return for investors looking to supplement fixed income, such as pension funds. The return for investors who had purchased the property at a lower price than our hypothetical EUR 100 and financed at lower long-term interest rates should also be higher.

As a result, we will not see a mass sale of rental properties by smaller investors to the owner-occupied segment if the controversial law is still passed after the elections. Especially if this is accompanied by flexible legislation to carry out the renovation task with as little hindrance as possible, there is sufficient availability of craftsmen & materials and there is subsidy available. The above calculation did not include subsidies, but there is already government money available for private investors (see ).