SustainaWeekly - Are emission reduction targets consistent with 1.5°C?

Reaching net zero by 2050 is the often heard ambition in climate policy. However, achieving net zero is a necessary but not sufficient condition to limit global warming. Specifically, it not only net zero but also the path towards net zero that is crucial as this will ultimately determine the total amount of carbon and other greenhouse gasses released into the atmosphere, which in turn determine the extent of global warming. In this week’s SustainaWeekly, we assess whether the current emission reduction targets in EU27 and the Netherlands are compatible with a 1.5°C scenario. Our next note looks at the current sustainable data disclosure requirements and their coverage/completeness as well as comparability. In our final note, we take a closer look at the disruptive nature of the energy crisis on Dutch industry and consider what the main effects of higher energy prices were, especially those of gas.

Economist: There are several paths to net zero, but only limited paths to 1.5°C temperature increase as this depends on the carbon budget. Even if the EU and the Netherlands meet current emission reduction targets, their contribution may not be sufficient for a 1.5 °C scenario. To stay within the 1.5°C - especially with a high degree of certainty - emission reduction targets for 2030 would need to be made more ambitious.

Strategist: The CSRD will set a common standard for ESG data disclosures, with the first deadline in 2025. Currently, ESG data disclosures are far from complete, especially related to scope 3 emissions, while comparability is weak, given that companies can use different methodologies. These issues are unlikely to be solved by the CSRD, which means that there should be close monitoring of the first data sets that will become available in 2025.

Sectors: Relatively high gas prices have been a strong incentive for many industrial companies to rapidly reduce gas consumption. Still, the Netherlands is about 70% dependent on gas imports, so the Netherlands has become a lot more sensitive to gas price fluctuations. It remains important for companies to further rationalise gas consumption. This can be done, for example, by further improving the energy efficiency of industrial processes.

ESG in figures: In a regular section of our weekly, we present a chart book on some of the key indicators for ESG financing and the energy transition.

Carbon budgets more crucial than net zero

There are several paths to net zero but only limited paths to 1.5°C temperature increase by 2100

This all depends on the carbon budget attached to the 1.5°C, 1.7°C and 2°C scenarios

Even if the EU27 and the Netherlands meet current emission reduction targets, their contribution may not be sufficient for a 1.5 °C scenario

Estimated cumulative emissions 2020-2050 are more in line with 1.5°C -1.7°C using carbon budgets based on current share of emissions

To stay within the 1.5°C, especially with a high degree of certainty – emission reduction targets for 2030 would need to be made more ambitious

Introduction

Reaching net zero by 2050 is the often heard ambition in climate policy. However, achieving net zero is a necessary but not sufficient condition to limit global warming. Specifically, it not only net zero but also the path towards net zero that is crucial as this will ultimately determine the total amount of carbon and other greenhouse gasses released into the atmosphere, which in turn determine the extent of global warming.The Paris Agreement has as its overarching goal to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”However, in recent years, world leaders have stressed the need to limit global warming to 1.5°C by the end of this century.That’s because the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change indicates that crossing the 1.5°C threshold risks unleashing far more severe climate change impacts, including more frequent and severe droughts, heatwaves and rainfall.The main question we would like to answer in this report is if the current emission reduction targets in EU27 and the Netherlands are aligned to this goal. We start with introducing the concept of the global carbon budget and ways to distribute this between countries.We then provide various estimates for carbon budgets and what they imply for global warming. We then compare these budgets with the estimated cumulative emissions for 2020-2050 under current government targets.

Carbon budget

A carbon budget is a concept used in climate policy to help to set emissions reductions targets in an effective way. It is the maximum amount of cumulative net global anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions that would result in limiting global warming to a given level. The IPCC estimated that the global carbon budget at the start of 2020 consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C with a likelihood of 50% was 500 GtCO2. For a 67% likelihood the global carbon budget was 400 GtCO2 and an 83% likelihood 300 GtCO2. For the 1.7°C degree scenario the budgets were: 850 GtCO2 (50%), 700 GtCO2 (67%) and 550 GtCO2 (83%). For the 2.0°C degree scenario the budgets were: 1350 GtCO2 (50%), 1150 GtCO2 (67%) and 900 GtCO2 (83%).

According to Earth System Science Data – Global Carbon Budget 2022, the annual manmade CO2 emissions were 36.6 GtCO2 in 2022 and there was a 380 GtCO2 carbon budget left at the start of 2023 (see ). These data are based on the 17th version of the global carbon budget and the 11th revised version in the format of a living data update in Earth System Science Data.

The carbon clock paints a more dramatic picture. It indicates that for a 1.5°C scenario currently 241 GtCO2 is left and for the 2.0° C scenario 991 GtCO2. So the carbon budget for the 1.5° C scenario would be depleted in less than 6 years at current emissions (see ). The clock is based on data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Annual emissions of CO2 – from burning fossil fuels, industrial processes and land-use change – are estimated to be 42.2 Gt per year, the equivalent of 1,337 tonnes per second.

Distribution of the global carbon budget by country’s share of current emissions

The main question is how to distribute this global carbon budget. There are a number of approaches. The first approach is probably the easiest method to do this. It is the distribution in line with the share of a country’s current emissions of the global emissions. This would imply that every country needs the same reduction trajectory. The result is that EU27 has a budget of 8% of the global carbon budget. In other words EU27 could emit 8% of the global CO2 emissions annually. This share has 2020 as base year because not all the data are available for 2021 and 2022. The Netherlands is responsible for merely 5% of the emissions of EU27.

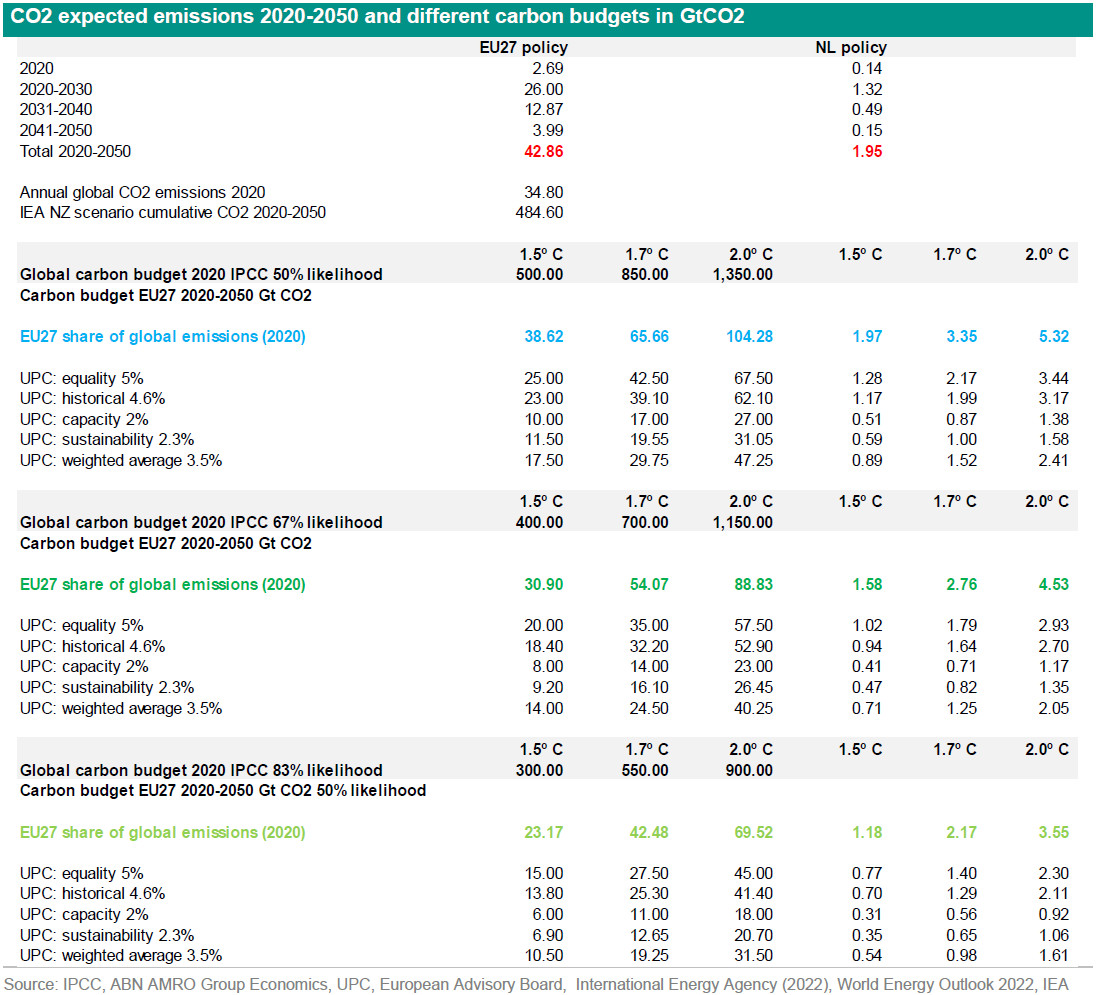

The next question is what are the EU27 cumulative expected CO2 emissions for the period 2020-2050 based on the 55% reduction target for 2030 (versus 1990) and net zero in 2050. Here we take the available data for 2020 and 2021 and assume a linear reduction path between 2021 and 2030. We also assume a linear reduction path between 2031-2050. We then add up these yearly CO2 emissions to come to the cumulative emissions of 42.86 GtCO2 for 2020-2050 (red in the table below). Based on the EU27 share of the global (8%) the budget for 1.5°C path with a 50% likelihood would be 38.62 GtCO2, for 1.7°C path 65.66 GtCO2 and for 2°C path 104.28 GtCO2 (blue numbers in the table below). Therefore the cumulative emissions would result in a path between 1.5°C and 1.7°C. In order to increase the likelihood of keeping the temperature rise at 1.5°C, the carbon budgets decrease as well. The results for the 67% likelihood are the dark green numbers and the likelihood of 83% the light green numbers. For example in the 1.5°C scenario with an 83% likelihood the carbon budget for EU 27 2020-2050 is only 23.17 GtCO2, almost half of the expected cumulative CO2 emissions if the EU’s targets are met. What would be the emission reduction target for 2030 need to be, to be in line with the carbon budget for 1.5°C path? To stay within the carbon budgets of 1.5°C CO2 emissions need to decline by 65% (with 50% likelihood) to 90% (83% likelihood). This again assumes a linear reduction path after 2030.

The same exercise can be done for the Netherlands. The Netherlands has a share of 5.1% of EU27 emissions. For the Netherlands the cumulative emissions 2020-2050 would total to 1.95 GtCO2 (see in red in the table). The budget would be 1.97 GtCO2 (1.5°C), 3.35 GtCO2 (1.7°C) and 5.32 GtCO2 (2.0°C) for 50% likelihood (blue numbers in the table above). Based on the cumulative estimated emissions would result in a path quite close to 1.5°C. However, the government would need to step up targets under increased likelihood scenarios.

Alternative methods for the distribution of global carbon budget

The distribution of the global carbon budget by the country’s share of emissions is probably the easiest way to do this. This approach has also drawbacks. It doesn’t take into account the historical emissions of a country, population and population growth and income per capita. There are several alternative approaches on how to distribute the global carbon budget, which some may argue is fairer to emerging and developing countries.

We start with four approaches presented by Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya BarcelonaTech (UPC) in a recent report (see ). The first approach is based on responsibility. This dimension aims to relate responsibility for contributing to climate change via GHG emissions of a country to its historical contribution to the problem.It considers the historical and present GHG emissions of a country and can be measured using the cumulative historical emissions per capita of that country. Simply put, the more emissions a country has emitted in the past, the lower its carbon budget in the future. This dimension dictates that the EU should be allocated 4.6% of the global carbon budget. The second dimension is based on capacity, specifically the degree of resources a country has to mobilize. The higher a country’s ability to mobilize, the lower its carbon budget. This dimension dictates that the EU should be allocated 2.0% of the global carbon budget. The third one is an approach based on equality. This means that each human has the same GHGemissions level. This dimension dictates that the EU should be allocated 5.0% of the global carbon budget. The last dimension is the right to development. It is the right of all countries to meet the needs of present and future generations. This dimension dictates that the EU should be allocated 2.3% of the global carbon budget. The equal weighted average of these approaches is 3.5% for the EU27. Based on this percentage the carbon budget of the EU is only 14 GtCO2 from 2020 (likelihood 67%), implying much more drastic emission cuts. If based on equality this budget would be 20 GtCO2. The table above shows the outcomes for the four approaches and the weighted average of the four (the rows with UPC).Moreover a study done by Air Pollution & Climate Secretariat shows that a carbon budget of 5.07% based on average population share. For the 67% likelihood the carbon budget would be 20.2 GtCO2 and for the 83% likelihood 15.21 GtCO2.

Furthermore, Climate analytics indicate that the cumulative emissions for the EU27 for the period 2020 to 2050 are between 12 and 23 GtCO2. In the 1.5°C compatible pathways assessed, cumulative CO2 emissions from 2020 to 2050 (excluding LULUCF) are 23-35GtCO2. If the average LULUCF sink from the above sources is included, then the EU27’s cumulative CO2 emissions from 2020–2050 would be 12-23GtCO2. This represents about 2.2-4.6% of the global 1.5°C compatible carbon budget. For comparison, the EU27’s fraction of global population is around 5.6%, and one would expect that as a developed region its carbon budget would be substantially less than its population share (see ).

Conclusion

There are several paths to net zero but only limited paths to a 1.5°C temperature increase by 2100. This all depends on the carbon budget attached to the 1.5°C, 1.7°C and 2°C scenarios. The IPCC estimated global carbon budgets at the start of 2020 to limit warming to 1.5°C, 1.7°C and 2.0°C at different likelihoods. There are different approaches to distribute the global carbon budget. One approach is to take one country’s current share of emissions. If we compare the expected cumulative emissions 2020-2050 for EU27 and the Netherlands with the different carbon budgets, these emissions are between the carbon budgets of 1.5°C and 1.7°C (50% and 67% likelihood). To stay within the 1.5°C carbon budgets CO2 – especially with a high degree of certainty – emission reduction targets for 2030 would need to be made more ambitious. This all assumes that targets will be met, but the policies are not yet in place to meet current targets. According to a report from June 2023 of Climate Analytics under current policies global temperatures are expected to increase by 2.7°C by 2100 and keep rising. Other approaches come with other outcomes as the table above shows. It would be a step forward if at the upcoming COP28 carbon budgets are formulated for the different countries. This will create clarity and help the enormous task at hand. But this will likely be a sensitive topic as there first needs to be an agreement on what approach to use.