Spotlight - German elections - ‘Grand coalition’ most likely result

On February 23, parliamentary elections will be held in Germany. Union leads the polls, with AfD in second place. However, a coalition between these parties is not feasible. Most parties, including CDU/CSU (Union), reject governing with AfD due to this party's extreme views. The most likely coalition is Union with SPD, as CSU does not want to partner with the Greens. Given the strained relationship between Union and SPD, the likelihood of significant reforms is low. Nevertheless, the chance of easing the so-called debt brake is high. Easing the debt brake would enable new investments by the government. These are urgently needed, as the German economic outlook hinges on improvements in physical and digital infrastructure.

This Spotlight summarises our full preview of the German elections, which can be found here.

The German elections have been brought forward from September to February this year. The shift is due to the fall of the government in November after Chancellor Olaf Scholz dismissed his Finance Minister Christian Lindner. SPD's Scholz accused FDP's Lindner of betrayal, claiming he deliberately aimed for the government's collapse. A major point of contention among the three coalition partners was public finances and whether the government should adhere to the so-called debt brake, which enforces budget discipline by law. FDP wanted to maintain it, while SPD and the Greens sought easing due to higher defence spending, support for Ukraine, and the ambition to modernize the economy.

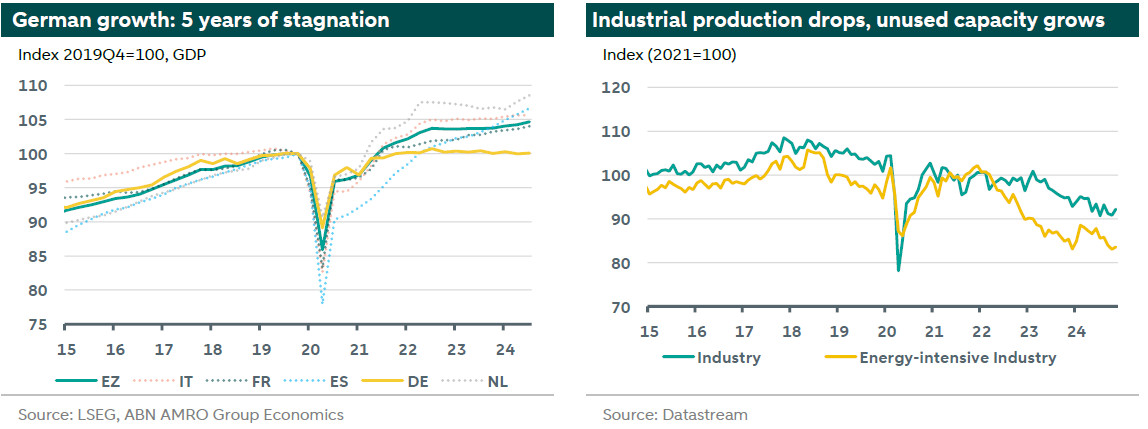

The elections take place against the backdrop of a weak economy that has shrunk for two consecutive years and faces rising unemployment. The threat of higher U.S. import tariffs also clouds the outlook for this year. The problem is that the contraction is not cyclical but structural. The industry, traditionally the pillar of the economy, suffers from high energy costs, deterring investments. Additionally, the U.S. government is luring European companies to the U.S. with the Inflation Reduction Act. Furthermore, competitiveness is under pressure as major companies falter. For instance, car manufacturers have long underestimated the importance of electric vehicles. Germany invests too little in digitization, resulting in slow internet and stagnant productivity growth. Moreover, worsening PISA scores indicate problems in education, while aging continues, with more experienced workers retiring. A further problem for Germany is that old certainties have vanished. Since Trump's election, security under the familiar NATO umbrella is no longer a given. Due to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Ostpolitik, once the cornerstone of German foreign policy, has been discarded. Cooperation with Russia, a strategic partner through the supply of cheap oil and gas, is no longer an option. Lastly, China has transformed from a buyer of German products to a formidable competitor, initially in wind turbines and solar panels, now also in electric cars.

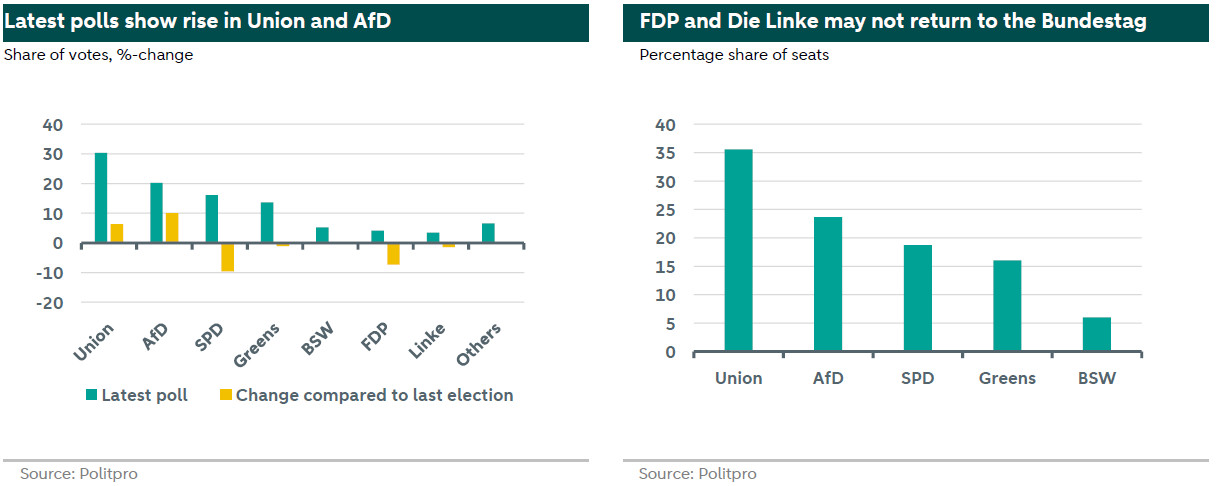

A total of fifty-six parties have registered to participate in the elections. Since not all are allowed to run and there is a 5% hurdle rate, only a fraction will enter parliament. A new party may enter the Bundestag: BSW, although it is uncertain whether this party will surpass the 5% hurdle rate. It is also unclear if FDP and Die Linke will exceed the 5% hurdle rate. Currently, eight parties have a realistic chance of gaining seats: AfD, BSW, Union, the Greens, Die Linke, FDP, and SPD. Caution is advised when drawing conclusions about the final election outcome based on current polls, as German elections are often unpredictable. For instance, SPD unexpectedly rose in the polls during the 2021 elections without SPD candidate Scholz having to do anything. His Union opponent, Armin Laschet, squandered his chances with an unfortunate, empathy-lacking remark about flood victims in southern Germany at the time. Additionally, a small difference in the election result can significantly impact the final composition of parliament. Currently, it is uncertain whether three parties with a chance of a parliamentary seat will surpass the 5% hurdle rate. After an article about the government's fall in the weekly Die Zeit, FDP fell below the hurdle rate in the polls. It is also uncertain whether Die Linke, which is also losing ground, and newcomer BSW will secure enough votes to enter parliament.

According to the latest results, Union leads with a polling share ranging from 26% to 31%, followed by AfD (18% to 22%). Both parties are set to gain compared to the previous elections. All other parties currently in parliament are losing ground: SPD (14% to 19%), the Greens (12% to 16%), FDP (4% to 7%), and Die Linke (3% to 5%). Newcomer BSW scores 4% to 7% in the polls. None of the parties can secure an absolute majority, meaning a coalition will need to be formed, as is customary in post-war Germany. The exact composition of this coalition is still unclear. Although party views differ, most parties agree on one thing: they do not want to govern with AfD due to the party's radical views that contradict the rule of law and democracy.

Based on current polls, a repeat of the 'Grand Coalition' between CDU and SPD is most likely. A combination of CDU and the Greens would also yield a majority on paper. However, CSU leader Markus Söder has indicated a preference not to partner with the Greens, although he may set aside his reservations if FDP joins. The 'Grand Coalition' could also theoretically be supplemented by FDP, whose party program most closely aligns with that of Union. However, this is not very likely. Firstly, because FDP must first surpass the electoral hurdle. Secondly, because Olaf Scholz may be reluctant to join another cabinet with Christian Lindner. Conversely, Union may not be enthusiastic about expanding the 'Grand Coalition' with Die Linke or BSW.

Based on the programs, 1) Union and FDP, 2) SPD and the Greens, and 3) AfD and BSW are most closely aligned. However, none of these combinations can secure a majority based on the polls, making a repeat of the 'Grand Coalition' the most likely outcome. The advantage is that this coalition can rely on a comfortable majority in parliament, allowing measures to be passed relatively smoothly. One measure on the agenda for the next government is adjusting the debt brake. Union was not in favour, but this stance is shifting. SPD's desire for adjustment has also increased. In a 'Grand Coalition,' there is room to soften the sharpest edges, for example, by incorporating exceptions for investments, defence, or climate policy. More room for this helps address economic issues and provides opportunities to play a constructive role in Europe and initiate Mario Draghi's policy agenda. Improving European security and strengthening common defence are high priorities.

At the same time, we must note that the party programs of Union and SPD have few overlaps, and where they do, they lack ambitious goals. This means that few far-reaching structural reforms are expected, although they are necessary, for example, in reforming the inefficient banking sector, revising the unsustainable healthcare and pension systems, and improving education. The plans for businesses and families are focused on preserving what exists instead of freeing up what could be. If important choices are postponed, uncertainty may persist, with businesses and families sitting idle. This would result in an economy that continues to falter, creating an ideal breeding ground for growing discontent, a situation that AfD would thrive in. That could mean that the AfD could score well during the next elections and will be difficult to exclude from government participation by 2029.