Raising our US growth forecasts

While January activity data came in on the weak side, we are raising our 2024 growth forecast by 0.3pp to 2.1%, which is now well above the consensus forecast of 1.6%. The change is driven by the more resilient labour market, which is likely to mean a shallower slowdown in consumption than we previously expected. With labour market tightness continuing to ease, however, we still expect the Fed to hit its 2% inflation target before the middle of the year, paving the way for rate cuts in June.

January activity data points to weak start to 2024

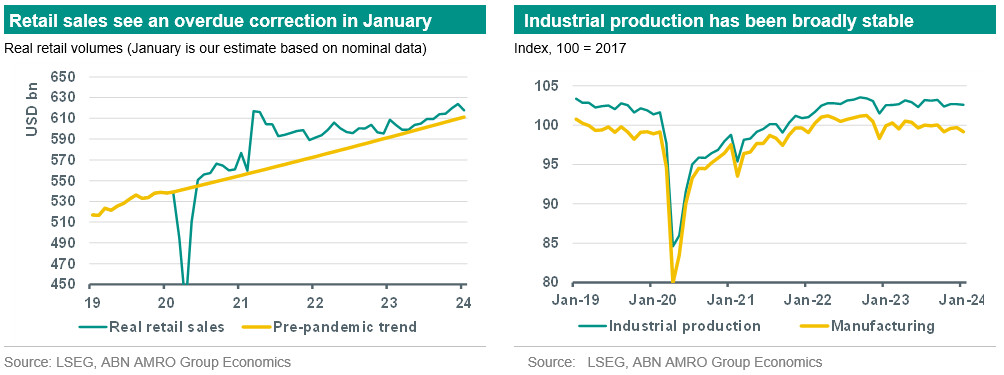

In contrast to the strong labour market data for January released earlier in the month, January activity data (released yesterday) covering the consumption and production side of the economy came in on the weak side. Nominal retail sales fell 0.8% m/m, following a downwardly-revised 0.4% rise in December, while industrial production fell -0.1% following a downwardly revised flat reading for December, likely impacted by poor weather conditions over the period. The weakness in retail sales followed a strong run in the data over the second half of last year (see below), and in our view represents an overdue correction given that goods consumption remains above trend in the US (see below). As such, the decline is consistent with our expectation for a slowing in activity in 2024, rather than being a cause for concern over the outlook.

Labour market resilience to mean a shallower slowdown

Indeed, despite the weak tone to the January retail sales data, we are actually raising our US growth forecast for 2024, and modestly lowering our 2025 forecast. For 2024, we are raising our forecast by 0.3pp to 2.1%, and for 2025 we are lowering our forecast by 0.1pp to 1.9%, reflecting the higher base of 2024. We were already above consensus in our growth forecast for 2024, at 1.8% vs 1.6%, and this change takes us further above the consensus forecast.

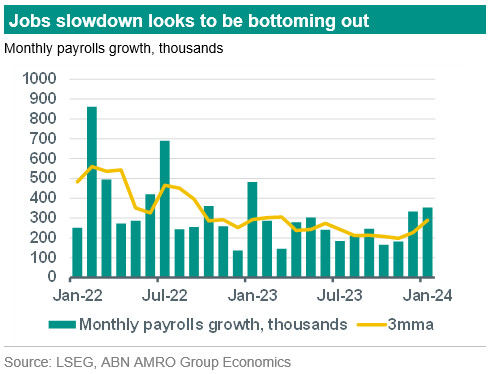

The update is driven by two main factors. The first is backward-looking – though the economy is slowing significantly, activity (particularly consumption) has held up better than expected in the last months of 2023 and moving into 2024, and this ‘carry-over’ effect by itself lifts our 2024 forecast. The second driver of the change is the strength in the labour market. While we do not take too much signal from the blockbuster January payrolls data, given that it is based on a relatively low survey response, the significant upward revisions to employment in Q4 2023 suggest a bottoming out in the employment growth slowdown. Given this, we expect only a marginal rise in unemployment (to around 4% from the current 3.7%), and this should therefore prevent a sharper slowdown in consumption growth.

With regards the quarterly growth outlook, we now expect annualised growth to slow to 1.5% in Q1 (previously 1.0%), with the trough in momentum expected in Q2 (1.0%). Growth is then expected to pick up but staying a little below trend at 1.5% in the second half of 2024. In 2025, we continue to expect falling interest rates to drive a recovery to trend growth in H1 25 (2.0%), and then somewhat above trend growth in H2 25 (2.5%).

Why we still expect some slowing in growth

Broadly speaking, the US economy is in remarkably good shape considering the shocks that have hit the economy, and the still-high level of interest rates. We judge the risk of recession to be relatively low, provided the Fed does indeed start lowering interest rates by the middle of this year. But this does not mean there are no headwinds facing the economy. Part of the reason for the resilience so far is the strength in real wage growth, driven by the sharp fall in inflation over the past 18 months. With inflation now bottoming out, that tailwind is easing. Indeed, on a 3m/3m basis, real per capita disposable income growth peaked at around 10% back in March last year, and has been cooling off since then, growing at a more normal 2% over Q4.

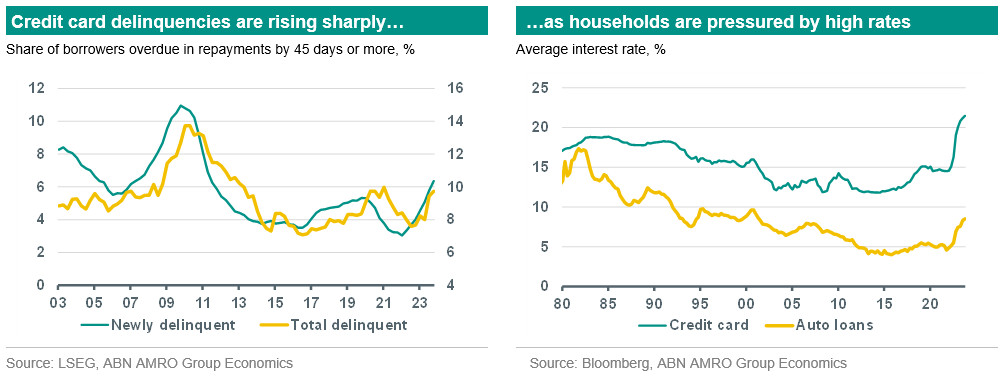

The other factor to watch is consumer credit growth, and related to that, the very low savings rate. As we have written before, higher income households are still benefitting from a dwindling savings buffer, while lower income households have been relying on credit card debt to maintain spending growth. Both of those factors are likely to be less of a tailwind going forward. Our estimate of excess savings suggests around 2/3 of it is now spent, and what is left most likely sits with the highest income households who have a lower propensity to consume. For the credit card spenders, delinquencies – defined as borrowers overdue with payments by more than 45 days – have risen sharply, likely pressured by the highest rates on credit card lending in over four decades. The rise in delinquencies is likely to weigh on spending, as an increasing share of households faces financial stress, and this could in turn cause credit card lenders to tighten lending conditions. To be clear, households in aggregate have very strong balance sheets – and so we do not see major systemic risks from this – but stress in the lower income groups can nonetheless bring down aggregate spending growth.

Could a more resilient economy stop inflation falling back to 2%? We think not

With economic growth expected to hold up better than we thought previously, a reasonable concern is whether this will prevent inflation falling all the way back to 2%. We don’t think so. Although unemployment has been stable at historically low levels over the past two years, this masks a significant easing in labour market tightness below the surface. Specifically, the job vacancy to unemployed ratio has fallen from a peak of 2.0 in July 2022, to 1.4 as of December – only a little above the pre-pandemic level of 1.2. This has been driven by both improved labour force participation as well as a cooling in labour demand.

this ratio is a much better indicator of the direction of wage growth than the unemployment rate. On some measures, for instance average hourly earnings, wage growth is already back near its pre-pandemic norm. On other – more reliable – measures such as the Atlanta Fed’s tracker, wage growth is still somewhat above its pre-pandemic norm at 5% as of January (the peak just prior to the pandemic was around 4%). However, keep in mind that prior to the pandemic, the Fed faced the problem of persistently below-target inflation, and so while wage growth might still be somewhat higher than a level consistent with 2% inflation, there is likely not much further to go – perhaps around 0.5pp. Given that wage growth is still on a declining trend, and the economy is expected to slow somewhat further, we think this sweet spot of c4.5% wage growth will likely be reached by the middle of the year.

The Fed’s target of PCE inflation, meanwhile, is already expected to be within touching distance of 2% when the January data is released at the end of the month (our forecast is 2.2%). With wage growth expected to continue normalising, and leading indicators for other major drivers such as core goods and housing rents suggesting continued disinflation, we expect PCE inflation to hit the Fed’s 2% target on a sustainable basis already by April. This will set the stage for the beginning of rate cuts in June.