Macro Watch - Tight labour market dampens economic growth potential

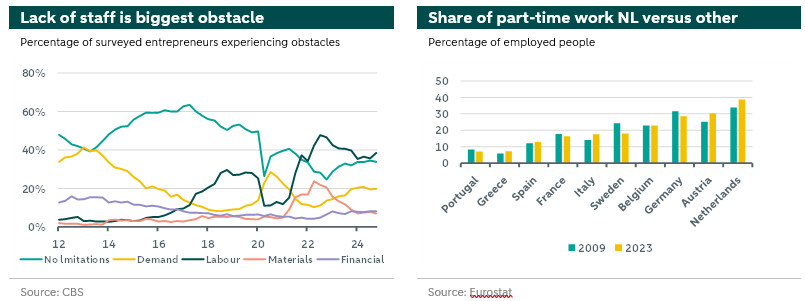

The active labour force has been growing steadily, but too slowly to meet all labour demand. Many vacancies are outstanding and business owners indicate in surveys that lack of staff is their biggest obstacle. The tightness in the labour market will continue for the time being, as the pool of people who can find work is small. The number of unemployed is low, the schedules of part-time workers who say they would like to work more hours do not necessarily match employers' work schedules, and those who are in the labour force but not in paid employment often have other commitments, such as study or informal care, or are kept from work by illness. The labour market is also at risk of remaining tight in the longer term due to an ageing population. With an increasingly weak increase in labour supply, the economy will grow more slowly and GDP growth per capita will weaken. This leaves less room to share the pain of social change. Where some citizens gain from a policy adjustment, others lose out. This will make it more difficult to implement reforms in the future.

Labour market tight despite substantial increase in the number of people in work

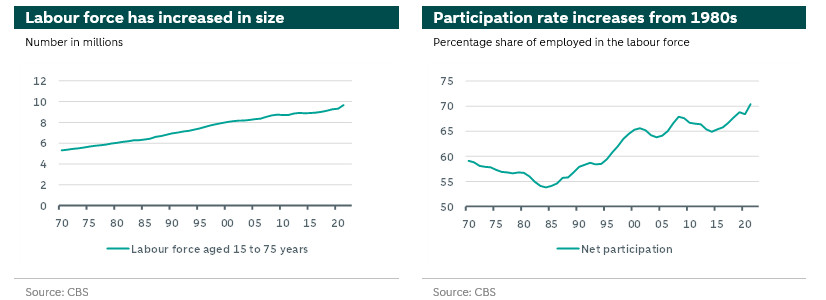

The labour force aged 15 to 75 years has grown since the 1970s and the share of it in paid jobs has also risen steadily. The net participation rate is now 73% compared to 59% in 1970. The increase is mainly because older people and women are more likely to be in paid work. Older people participate more because pre-pension schemes, such as early retirement, have been abolished and the retirement age is linked to rising life expectancy. Women are participating more due to cultural shifts. The traditional model where the man works outside the home and the woman stays at home has ceased to be the norm. Furthermore, the tax system has been individualised and tax adjustments have been made, making it financially attractive when both partners work.

Despite the increase in the number of employed people, the labour market is particularly tight. Unemployment, at 3.7% of the labour force, is at a historically low level, while the number of outstanding vacancies is at an elevated level. The increased labour shortage is also reflected in UWV's tension indicator, which measures the number of outstanding vacancies against the number of people unemployed for less than six months. This subgroup of unemployed people has a stronger attachment to the labour market, is therefore easier to employ and moves on to a job faster than unemployed people who have been on the sidelines for longer.

Many people are still on the sidelines

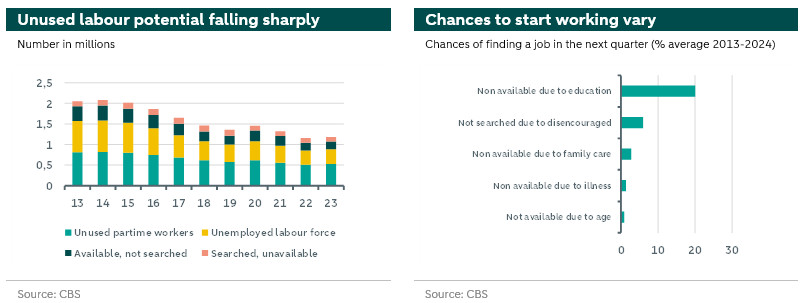

Open vacancies can also be filled by groups other than the unemployed. People looking for work are not necessarily registered as unemployed. At 963,000, for instance, the number of jobseekers registered with UWV is much higher than the 365,000 people registered as unemployed according to CBS. Besides unemployed people, CBS also counts semi-unemployed people; those who have recently (in the past two weeks) looked for work but are not available for it in the short term (within two weeks), or vice versa: those who have not looked but are available. Furthermore, CBS counts part-time workers who would like to work more hours than they currently do. The total group of unemployed, semi-unemployed and part-time workers who would like to work more hours is also referred to by CBS as the unused labour potential. According to the most recent figures, this group is 1.2 million people.

However, it is too short-sighted to think that those belonging to the unutilised labour potential can immediately start working and could fill the open vacancies. This is because they have other activities, such as studies and caring responsibilities, or suffer from health problems, which prevent them from getting a job. In addition, they may consider themselves too old to work, although this is relative given the increased participation of 55- to 75-year-olds following the increase in the retirement age. Furthermore, skills sometimes do not match what is required. Targeted retraining can then help. Also, the distance between home address and the location with suitable vacancies may be too great. Higher travel allowances, improved infrastructure, and a wider housing market so that people can move easily can alleviate the latter problems.

Of these, however, few can get straight to work

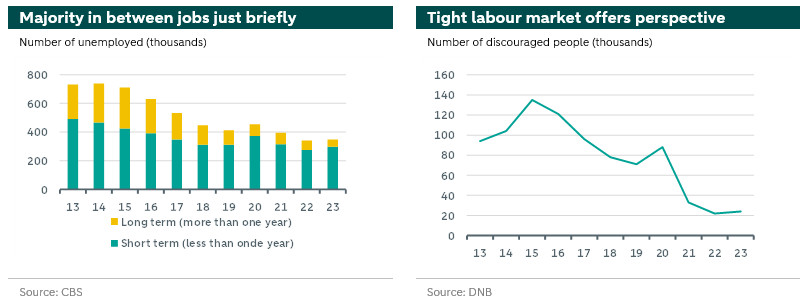

Within the group belonging to the unused labour potential, there are thus considerable differences in opportunities to move on to a job. The unemployed are the most likely to do so. Historical analysis shows that about a third have a job a quarter later. The majority of the currently unemployed have been out of work for less than a year. In fact, this is frictional unemployment. Due to information frictions, it takes time for workers and employers to find each other. This means that there is little incentive to bring down the total number of outstanding vacancies through even lower unemployment.

Among part-time workers who would like to work more hours, there are some leads to ease labour market tightness. This group numbered 517,000 in the second quarter of this year. On average, they want to work 8.8 more hours, so on paper 130,000 FTEs could be filled. In practice, however, this number will be much lower. First, because the schedules of employers and employees, mostly on-call workers, do not necessarily align, making those desired extra working hours difficult to schedule. Second, because part-time workers who want to work more hours cannot necessarily work in sectors where the need is greatest. Third, because the figure is biased upwards: opposite to part-time workers who want to work more are workers who would prefer to work fewer hours than they currently do.

Among the semi-unemployed, opportunities to increase labour supply and fill vacancies are even more limited than among part-time workers. The 113,000 semi-unemployed who have looked for work, but are not available for the labour market, are likely to find a job. Only, they often cannot start work immediately, for example due to study commitments. Only when training is completed do they enter the labour market.(1) Then there are 185,000 semi-unemployed who are available for work but have not looked for it. Their chances of finding work are even lower because they are long-term unemployed, or have lost confidence in finding a job due to previous disappointing job application experiences. On the positive side, the number of those ‘discouraged’ by labour market tightness is historically small. Due to the ample job supply, people who were previously discouraged have still found jobs and the number of long-term unemployed is low.

Temporal factors contribute to labour market tightness

In recent years, cyclical factors have exacerbated labour market tightness. As a result of all government support measures, few companies went bankrupt. Consequentially, fewer workers lost their jobs. Profit margins were also relatively high, making it easier for companies to retain staff. Another contributing factor was that labour was cheap, as real wages were under pressure due to high inflation. Furthermore, the persistent labour shortage encouraged employers to ‘hoard’(2) workers, which added to the shortage problem. However, the tendency to retain workers even when there is no work for them pushes down productivity. Such a situation cannot persist for long, as it comes at the expense of profitability, especially if real wages increase again as wages rise and inflation softens. The latter is already happening and bankruptcies are also on the rise again.

Against this background, the signs that the labour market situation is turning around come as no surprise. In the second quarter, the number of unemployed was 377,000, 11,000 higher than in the same quarter a year ago. The number of vacancies decreased by 21,000 to 396,000. The vacancy rate, or the number of vacancies per thousand jobs, fell from 46 to 44. Nevertheless, the labour market situation is still tight. At 3.7%, the unemployment rate is well below the 5.8% average of the past 20 years and is just above the record low of 3.3% over that period. Companies also continue to struggle to find staff. Business owners still indicate in surveys that staff shortage is the main obstacle for them.

Labour supply under further pressure due to demographic shifts

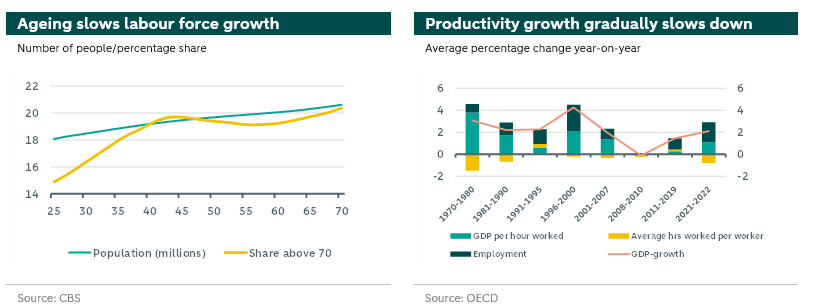

Despite these recent signs of turnaround, tightness in the labour market will continue due to the demographic outlook. Labour force growth is gradually coming under pressure due to the combination of ageing and de-greening. While the number of young people completing education and entering the labour market is declining, the number of older people retiring and leaving the labour market is increasing. Furthermore, tolerance for migration is declining and the reservoir of potential Central and Eastern European labour migrants is being depleted, as the population there, like in the Netherlands, is ageing and prosperity gaps have narrowed. When it becomes more difficult to attract foreign workers, migration can no longer serve as a valve for the labour market.

There is also little room for further increases in participation rates, although there is some room for improvement there. For instance, with rising life expectancy, the retirement age will shift upwards. If older people succeed in working longer, this will contribute to a larger labour supply. In addition, the participation rate may increase if the population's health improves and fewer workers drop out. Preventive policies, healthy working conditions and enjoyable work are essential for this. When people find their work interesting and meaningful, absenteeism is lower on average. Finally, improved childcare can encourage parents to work more.

Although the Netherlands leads the ‘part-time work’ list, opportunities to work more hours are limited. In fact, the number of hours worked per person of working age is higher than in other countries. While working even more hours leads to higher wages, it also comes at the expense of free time. The trade-off between wages and free time will depend on individual preferences. With an ageing population, these are likely to shift towards more free time, also because the ratio of informal carers to older people is falling and the care tasks per working person is increasing.

This does not alter the fact that individual preferences may change. Lower taxes on labour and a simpler benefits system, for example, could increase labour supply. For the Netherlands, this would mean a relaxation of the policy of wage moderation that has been in place since the Wassenaar Agreement in the 1980s. The aim of wage moderation is to stimulate labour demand. This was appropriate in the context of high unemployment, as in the 1980s, but not in the context of labour shortages. It increases labour shortages, especially as it weakens the incentive for labour-saving investment.

Productivity becomes main pillar for GDP growth

Because of slower labour force growth and limited scope to increase participation and hours worked, the conclusion is compelling that labour supply growth risks weakening. This means that GDP growth, which is the sum of total hours worked and productivity (output per hour worked), is weakening. According to the latest CBS projections, labour force growth will decrease from 0.3% since the start of the new millennium, to 0.1% in the period to 2070. At the same number of hours worked per worker, this leads to a moderation in GDP growth of 0.2 percentage points. But demographic estimates are subject to uncertainty, as the outcomes depend heavily on assumptions about migration. The European Commission, for instance, has produced scenarios whose outcomes are much lower than those of CBS.

GDP growth in the future will thus increasingly rely on productivity growth, which is also under pressure. Productivity growth, measured by GDP per hour worked, has weakened from an average of 3.8% in the 1970s to an average of 0.8% from the new millennium onwards. Limiting gas extraction has contributed to this. But the Netherlands is certainly not alone in this downward trend, which is caused by a range of factors. For instance, the improvement in schooling levels, a key determinant of labour productivity, is stagnating. In addition, a smaller and smaller number of companies are responsible for productivity growth and innovations are less easily trickling down to other companies. Furthermore, it is also becoming increasingly difficult to innovate. Unfortunately, the number of promising ideas for innovations does not keep up with the number of researchers. Finally, an ageing population is leading to a shift in demand towards healthcare, a labour-intensive sector with historically low productivity growth.

It is possible that the implementation of AI could reverse the downward trend in productivity growth. Companies are investing heavily in data centres and software development, laying the foundation for further AI applications. The outcome will depend partly on how quickly AI is embraced. Currently, diffusion is fast compared to previous breakthrough technologies. Recent studies show that AI is already helping to perform certain tasks more efficiently. Less experienced workers seem to benefit. However, which tasks AI can replace and what its macroeconomic effects will be remain a matter of debate.

In addition, productivity growth can be stimulated by policy. Governments can invest in knowledge development and education. They can provide funding to innovative firms that do not have access to private finance. They can provide more certainty about future policy directions so that entrepreneurs know where they stand and dare to invest. Furthermore, they can strengthen economic dynamism, so that labour and capital move from low- to high-productivity activities. This involves steering the economy towards companies and sectors that promote social welfare. This is done by discouraging socially undesirable activities and activities that make high demands on scarce resources by taxing them more heavily and setting stricter standards. This can free up labour and capital for other, more socially relevant activities.

Lower economic growth hinders social reforms

We expect that productivity growth could still average 0.8% over the next decade, but after that, once the fruits of the AI revolution are reaped and the trend of softening continues, it will decline towards 0.5%. Combined with the demographic outlook and its impact on the labour force, which are also subject to uncertainty, this means that GDP growth will be in the range of 1% and 1.5% over the next decade and then weaken towards a range of 0.5% to 1%. As overall population growth continues, per capita GDP growth risks stalling. In such a situation, it will become more difficult to implement social reforms because the pain they entail will be harder to distribute. Progress for some leads to regression for others. This places a big responsibility on current policymakers. The longer they wait to make necessary structural reforms, the harder it becomes to implement them.

(1) When times are low, such as at the time of the credit crisis, many young people choose to increase their labour market opportunities and continue studying, while when the labour market is tight, they have an incentive to start working quickly. The latter may prove unfavourable in the longer term, as there is a relation between education, productivity, and future wages.

(2) The European Commission has developed an indicator for ‘staff hoarding’ based on the percentage of entrepreneurs who indicate in surveys that they anticipate a drop in sales but still retain/expand staff.