Macro Watch - Looming fragmentation will make European Parliament less vigorous

The latest polls predict a shift to the right, and a more fragmented European Parliament after the next Parliament elections in June. Increased fragmentation will hinder creating coalitions and reaching voting majorities. Therefore, we expect a policy poor period is ahead of us.

We also expect a change in policy focus. After June, a majority in the European Parliament will be supportive of restrictive immigration policies.

Eurosceptic parties favour national autonomy over centralized policies, thus underutilizing the full potential of the common market.

Majorities for more latitude for individual member states will become likely, which could jeopardize fiscal prudence.

Another shift is expected with regards to the environment. The majority of the new Members of Parliament will probably advocate for a more gradual transition, increasing the risk that the transition pathway moves away from an 'orderly Net Zero' scenario towards a delayed transition scenario.

Autors: Philip Bokeloh; Sonila Metushi

European Parliament elections in June

This summer Europe goes to the ballot box to vote for the European Parliament. From 6 to 9 June more than 400 million eligible voters can choose the members of the European Union’s only directly elected institution for the tenth time since 1979.

Originally the European Parliament functioned as an advisory board. However, this has changed. Nowadays, it is rather functioning as a normal National Parliament. Its 720 parliamentarians are directly elected by their respective 27 national populations. It has co-legislative power in nearly all policy areas. It has the power to approve the European Unions’ budget and the future European Commission.

An important distinction though is that the European Parliament lacks the right to submit laws, a right which is almost entirely reserved for the European Commission*. In that sense the European Parliament is an important institution within the European Union, but not necessarily the most powerful one. Nevertheless, the composition of the European Parliament serves as an important guide for European Union policy making.

Radical right set to win seats

After the 2019 elections the policy focus shifted to more progressive issues such as greening the economy, regulating technological progress, and implementing social policies. For instance, a Green Deal was signed to speed up the reduction of carbon emissions and to stay within the boundaries set by the Paris agreement. The AI-act was passed to promote the uptake of human centric and trustworthy AI, and regulation was drafted to ensure that companies’ supply chains comply with human rights and labour laws.

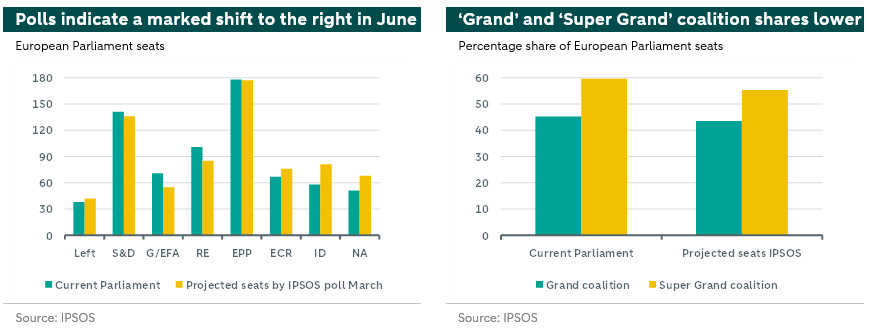

At the next elections, the traditional mainstream parties EPP, S&D and RE are expected to lose seats, just like the G/EFA**. Many polls predict significant gains for the centre-right and extreme right. The ID group can be expected to gain between 10 and 30 seats and could overtake RE as the third largest group in Parliament. The Eurosceptic ECR is also projected to gain 5 to 15 seats. Some parties are negotiating joining this group, enabling it to potentially overtake the third place.

This outcome is in line with the long-term trend of fragmentation in European politics. Both on a national and on a European level traditional parties lose support, while smaller, more radical parties on the left, but particularly on the right, gain support. Populist, authoritarian, nativist parties are topping the polls in various member states. However, the EPP seems to remain the largest and most powerful group in Parliament that will be able to influence the political agenda most. For the first time, a populist right coalition might appear, consisting of the EPP, ECR, and far-right ID.

As a result of the expected shift ‘left’ (S&D, G/EFA and The Left) and ‘centre-left’ (S&D, G/EFA, The Left and RE) coalitions’ minorities shrink even further in size. The ‘grand’ and the ‘super grand’ coalition will no longer be as dominant. The ‘grand coalition’ of EPP and S&D, which lost its majority in 2019, continues to shrink to 43% of the seats according to the latest IPSOS poll. The majority of the ‘super grand coalition’, that also includes RE, shrinks to 55% of the seats. Reaching voting majorities in Parliament with only 55% of the seats will prove difficult though. The EPP, S&D and RE each consist of national parties, which opinions and voting behaviour may diverge. Therefore, the ‘super grand coalition’ will increasingly have to seek support from non-attached Members of Parliament to secure majority votes.

Policy poor period ahead with increased focus on national issues

The expected political shifts mark a change in both policy making and policy focus. Regarding the policy making, European politics tends to be about creating coalitions. Coalitions on policy issues in the European Parliament tend not to be the result of formal agreements. Instead, political groups decide how to vote issue by issue. Research by the European Council on Foreign Relations shows that in the past term centrist coalitions (EPP, S&D, usually also RE) generally won over economic, fiscal, and monetary affairs. Centre-left coalitions (S&D, RE, G/EFA and The Left) tended to win over social issues and the environment, and centre right coalitions (EPP, RE, ECR and sometimes ID) over rural development, agriculture, and fisheries.

However, creating coalitions will become difficult in a more fragmented Parliament. Creating coalitions is also complicated because the policies advocated by the various radical right-wing parties are not necessarily consistent with each other. These parties might be united in their dislike for cultural and political establishments and centralized European policies, but they lack a common program. Hence, the current polls could well be the harbinger of a relatively policy poor period. Meanwhile, changing existing legislation, for instance introduced by the Green Deal, will also be challenging in a more fragmented Parliament. Though the current system may create difficulties in passing legislation, it also generates stability.

Fragmentation of votes along various major issues

Regarding the policy focus we must recognize that Europe is enduring various crises. The economy consecutively went through a financial, a euro, a health, and an energy crisis. Covid shocked the health system and tested social cohesion. Fire hazards and floodings due to climate change are causing financial damage. The arrival of refugees is stirring social unrest. The post-Cold War peace dividend seems to have ended after the Trump presidency and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The wars in Ukraine and Gaza stoke feelings of insecurity. In response, European member states are starting to invest in defence and intensify their cooperation.

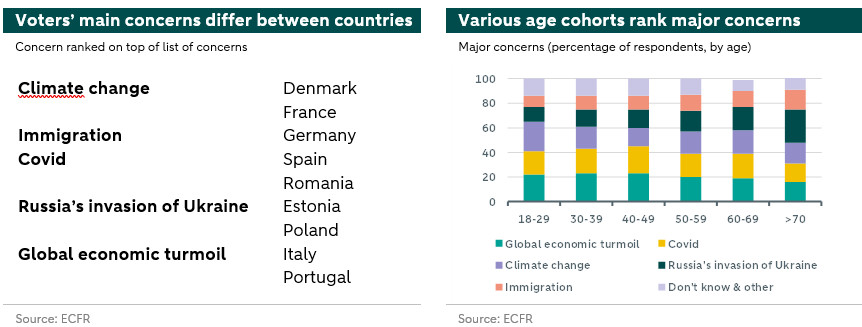

European citizens are affected by these crises to different degrees, depending on their nationality, age, gender, and education. For instance, Italians indicate more often that they worry about the state of the economy. The younger generation seems to be more concerned about climate change than elderly Europeans. Women appear to have suffered more from Covid then men. And lower educated prove relatively worried by migration. These differences explain the and the increase of political fragmentation. Not necessarily along the left-right divide, as in the past, but along the lines of the various crises. The June elections will be shaped by competing worries about climate change, migration, military conflict, and the economy.

Migration and climate change are in the limelight

As climate change and migration generally prove most motivational to cast a vote, these two topics will probably dominate the elections. In contrast to 2019, when concerns about climate change prevailed, the next elections seem to concentrate on migration. After June, a majority in the European Parliament will likely be supportive of restrictive immigration policies.Another shift is expected on the environmental policy front. The green agenda hardly resonates with right wing parties that rather try to scale down on climate ambitions. The EPP and RE, which used to be proponents of the Green Deal, are getting less ambitious on the environment. They have already indicated that environmental policies will not be a priority in the next legislative period. The majority of the new Parliament will probably advocate for a more gradual transition. Such a change could complicate the EU’s path towards net zero.Some radical parties, such as Le Pens FN and Geert Wilders PVV, maintained close (financial) ties with Russia in the past. Currently their leaders are keeping a low profile on this issue, but at some point, they might resume their positive stance on Russia. However, the radical right wings’ views diverge on this topic. Italy’s Fratelli d’Italia, Finland’s Finns party and Poland’s PiS are committed to a Ukrainian victory, just like a large majority in Parliament. Therefore, the European Parliament is, and probably remains, in favour of supporting Ukraine. Recently the European Commission decided to boost the defence industry and to provide adequate support to Ukraine.

The European Parliament is less unified on economic integration by implementing a capital market union and a common industrial policy strategy. Progress on these two themes will be complicated if national interests become dominant. This will hinder productivity growth and competitiveness. Instead, after a shift to the right Europe’s policies will rather veer towards trade protectionist measures such as the Electric Vehicle probe, which seeks to determine whether Chinese Electric Vehicle producers benefit unfairly from state subsidies. Though a more right-oriented European Parliament should embrace market-based measures, it may also prove sensitive to subsidy requests from companies that seek protection from foreign competitors, which tends to be costly, constrains competition and hinders productivity growth.

The elections are already shaping policies

Though next June’s elections do not affect the composition of parliaments or governments of individual member states, the outcome will shape national policies. The terms of office of governments shortened significantly in member states since the beginning of the new millennium, which led to more frequent changes in the composition of the European Council. Given the shortened terms governments are paying closer attention to interim messages conveyed by their national voters and attune their policy agendas to what appears to be opportune and politically feasible.

Actually, national policies already changed in the run op to the European Parliament elections. For instance, French President Emmanuel Macron dismissed his prime minister and replaced the government to assure support from conservative voters. The new prime minister Gabriel Atal is stressing more conservative themes. Also, the fact that seven out of eleven new ministers previously served in right wing administrations, signals a rightward move.The prospected outcome in June is influencing European policies as well. Earlier this year the European Union closed multi-year, multi-billion euro deals with Egypt and Mauretania for holding back migrants. The deals resemble the Tunesia deal, which didn’t prove very successful so far. And more recently, after ten years of discussion, the European parliament adopted a reform of the asylum and migration pact, which includes fast-tracking asylum claims directly at the external borders.

Moreover, Europe’s sustainable supply chain act was delayed to 2029 and attenuated in both scale and scope. The same could happen with Europe’s green ambitions. In response to the farmers protests European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen scrapped the proposal to halve pesticides use, cut the target for reducing agricultural CO2-emissions, and issued a survey among farmers asking them which regulations they find most obstructive. Meanwhile, the new Council of EU-president Belgium is looking for ways to postpone the Nature Restoration Law, which requires EU member states to implement restoration measures in at least a fifth of land and marine areas by 2030, and in all ecosystems that need restoration by 2050. The Nature Restoration Law is an example of a law that probably would have lacked a majority in the European Parliament new composition according to the recent polls.

What is in store?

This begs the question which parts of the recently introduced policies may be adjusted, postponed, or even scrapped. The smaller size of the grand and super grand coalitions likely means that the centre will no longer be as dominant on some policy issues. The EPP will start cooperating more often with the right side of the political spectrum, rather than seeking partnership with the S&D. Particularly on issues where voting margins were thin.

With regards to migration legal limits could increasingly be tested. The perception of what the rule of law is about, is changing. By some politicians it is interpreted as the capacity of the state to be efficient and effective in ensuring safety and protection, even if regulations with regards to privacy, discrimination and equity need to be set aside, while the rule of law pertains to defending citizens from state interference. This conversion could be counterproductive as it erodes the very values on which Europe’s unification is based.

Radical right-wing parties are Eurosceptic and favour national autonomy over centralized policy making. Against this background majorities for latitude for individual member states will become more likely. On a fiscal level this entails risks for of individual member states. On a financial market level this will impede progress on the Capital Markets Union. It will also complicate advancing a common industrial policy agenda, integrating the internal market, and making progress with regards to consumer protection.

Regarding the environment, it is of importance to halt the politization of climate agenda. Delayed implementation of the Green Deal increases the risk that the transition pathway moves away from an ‘orderly Net Zero’ scenario towards a ‘delayed transition’ scenario. A delayed transition scenario will eventually trigger a sharper bend in climate policies after 2030. In a delayed transition scenario climate litigations will increase, calling governments to comply with and implement their own legally binding mitigation commitments to the Net Zero target.

* At EU level, the right to initiate legislation is reserved almost entirely for the European Commission (Article 17(2) TFEU). Both the Council of the European Union (Article 241 TFEU) and the European Parliament (Art 225 TFEU) have an indirect right of initiative: they can request the Commission to come forward with a legislative proposal and the Commission needs to justify if it refuses to do so. In addition, Parliament has a pro-active role in pursuing political influence on overall legislative planning and agenda setting.

** Currently there are seven political groups in the European Parliament: the Christian Democratic European People's Party (EPP); the Socialist and Democrats (S&D); the centrist/liberal Renew Europe (RE); the Greens/European Free Alliance (G/EFA); the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR); the most right-wing group, the Identity and Democracy Group (ID) and the Left group (GUE/NGL). In addition, 52 of the current 705 Members of the European Parliament are 'non-attached' (NA), meaning they belong to no political group. A Dutch example is Agrarian BBB.