Macro Watch - Can defence spending revitalise the eurozone economy?

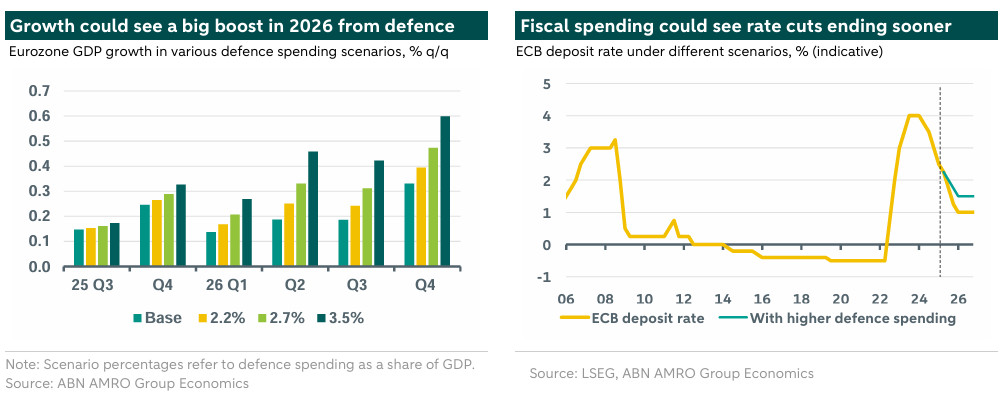

Higher defence spending will likely significantly lift growth in 2026, in both the eurozone and the Netherlands. A lot will depend on how quickly spending ramps up, and the extent to which Europe can re-tool industry. All else equal, this is likely to mean the ECB cutting interest rates less than we currently expect.

The confluence of Germany’s federal elections and the US pulling back from the decades-long transatlantic alliance is fomenting a revolution in European defence spending. Germany is abandoning fiscal frugality in the face of an existential threat to Europe’s independence and security, while the EU is likely to significantly loosen the fiscal rules, supported by c0.8% of GDP in new common debt financing. In this note, we explore the potential impact of these changes for the near-term growth outlook. In the very near-term – at least for this year – the impact is expected to be small, but the fiscal boost could be potentially game-changing for 2026 and beyond. In a reasonable middle ground scenario, we think 2026 growth in the eurozone could be lifted by 0.3pp, or 0.4-0.5pp when including Germany’s infrastructure spending plans. In a downside scenario, the boost would be only 0.1pp, but in a more optimistic scenario the impact could be as high as 0.8pp. Beyond the near term, the academic literature suggests that structurally higher defence spending can have major spillover effects to long-term productivity, thereby lifting potential growth – by 0.25% for every 1% of GDP spending increase. In short, while raising defence spending is initially costly, it can potentially pay for itself over the longer run.

All else equal, this boost to growth would be enough to see the ECB cutting interest rates less than we currently expect, with the deposit rate settling at, say, 1.5% instead of our current 1% expectation. But with potentially much more aggressive US import tariffs expected to be announced on 2 April, which poses major downside risks to the outlook, we refrain for now from making a formal change to our base case.

Impact depends a lot on assumptions

1) Spending rise: 3.5% of GDP is the magic number, but 2.7% more feasible in the short term

Assessing the impact of higher defence spending is not straightforward. The first step is determining what kind of increase is likely – and for that matter feasible. The eurozone in aggregate currently spends around 1.8% of GDP on defence, just shy of the 2% NATO goal (the broader EU spends around 2%, thanks to heavy hitters like Poland and the Baltics). An suggests that for Europe to be militarily independent from the US, spending would have to rise to around 3.5% of GDP. This is consistent with the European Commission’s implicit target, with the new fiscal rules enabling an additional 1.5% of GDP to be spent on defence. However, this looks to be at best a longer-term goal rather than one that is realistically feasible in the near term, at least for the eurozone aggregate. Even with the Commission’s looser fiscal rules, a number of member states – notably Italy and France – simply do not have the fiscal space to raise spending this much, without cutting other spending or raising taxes (both of which would likely more than offset any positive GDP impulse). Others still lack the same sense of urgency – particularly those far away from the frontline in Ukraine, such as Spain, but also the Netherlands (see below), where political divisions are likely to prevent a big bang surge in spending.

Given the above, we estimate a much more reasonable near-term target is 2.7% of GDP by end 2026. This assumes the German bazooka is fully utilised, and that the fiscally-challenged countries draw on the EU’s new €150bn SAFE common debt instrument. A much more positive scenario, where aggregate spending rises to 3.5% of GDP by end 2026, would likely see a number of countries testing the limits of fiscal credibility. This is unless the EU is able to agree common debt financing on a much bigger scale, which would require unanimity among the EU27. This could happen, but we would not have it as our base case. On the downside, the new German government might struggle to ramp up spending as quickly as it would like, and other governments may struggle even more than we currently assume in the face of political and/or financial market pressures. In this downside scenario, we assume spending rises to only 2.2% of GDP by end 2026.

2) Fiscal multiplier: Likely to be low initially, but ‘Buy European’ could raise it rapidly

The growth impact of higher defence spending hinges on the fiscal multiplier. Multipliers vary significantly depending on 1) the type of spending, 2) the macro-economic environment (the degree of slack), and 3) import intensity. on defence spending suggests a multiplier ranging between 0.6-1.0, perhaps even higher in the long-run when factoring in potential spillovers to productivity growth. In other words, to a large extent the economy should expand to accommodate the increase in spending. However, much of the academic literature is centred on the US, which has a highly developed and mostly self-sufficient military-industrial supply chain. This is not the case in Europe, where in the most recent period, as much as 80% of defence procurement happened outside the EU. As such, the relatively high multipliers that apply to the US are unlikely to prevail in Europe; at least, not until the military-industrial supply chain has been developed to a sufficient scale.

---------------

Box:

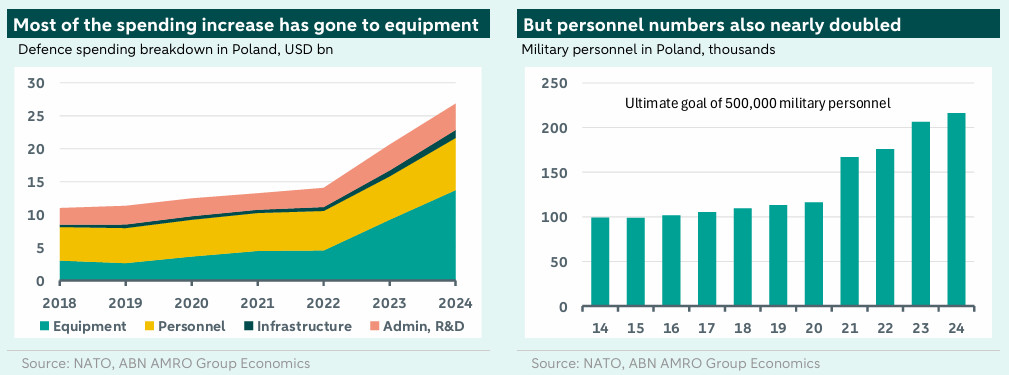

What can Poland’s experience tell us about rapid increases in defence spending?

Poland is an interesting case study in what happens when a country sharply raises its defence spending. In just two years, Poland raised its defence spending as a share of GDP from 2.2% in 2022, to 4.1% in 2024. So, the first lesson from Poland is that spending can and does rise very rapidly when the political will is there. However, Poland’s experience also shows that such a rise – at least initially – probably comes with a low growth multiplier. According to NATO data, some 72% of Poland’s increase in spending went on equipment, and we estimate – based on – that 3/4 of that increase went to higher imports. Most of these imports came from the US, such as Apache helicopters and HIMARS rocket systems, but also from South Korea, which is a big producer of tanks, such as the K2 Black Panther. This suggests that in Poland’s case, already over half of the increase in spending ‘leaked’ out of the economy through higher imports.

Of the remainder, around 15% of the spending increase went to personnel, 8% to admin/R&D, and 5% to infrastructure. It is notable that despite a near doubling in recent years in military personnel, from 116,000 in 2020 to 212,000 in 2024 – an 86% rise – spending in this category during that time rose by only 42% (Polish Prime Minister Tusk recently announced a goal to increase military personnel to 500,000, and to provide military training to every man).

For the spending that went to the domestic economy, some of this would have led to crowding out, both in the labour market and investment, i.e. some portion of this spending likely displaced activity that would have occurred elsewhere in the economy. Taken together, this suggests a fiscal multiplier considerably below 0.5, with perhaps a reasonable assumption closer to 0.2-0.3. The multiplier is however likely on a rising trajectory. For instance, contracts for South Korean tanks involve up to 80% of production ultimately moving to Poland, and with servicing by Polish companies. Given the changed geopolitical environment and the pressure governments will be under to achieve growth spillovers from higher defence spending, the political will is clearly much greater to and to rapidly increase domestic production capacity.

---------------

Under normal circumstances, this would take many years, but the changed geopolitical context has clearly focused minds. Some member states have indicated either that they are reconsidering orders of US defence equipment, or that future spending increases should primarily be spent within the EU. For instance, Germany has indicated that it will be buying Eurofighter jets instead of F-35s, while Portugal is reconsidering its plans to order F-35s from the US. Moreover, the new €150bn SAFE fund is likely to stipulate at least 65% of defence procurement is made up of EU content, with the remainder only allowed to be spent on equipment from third countries that have signed a security pact with the EU (this would therefore exclude the US, UK and Turkey, but include Norway, Japan and South Korea).

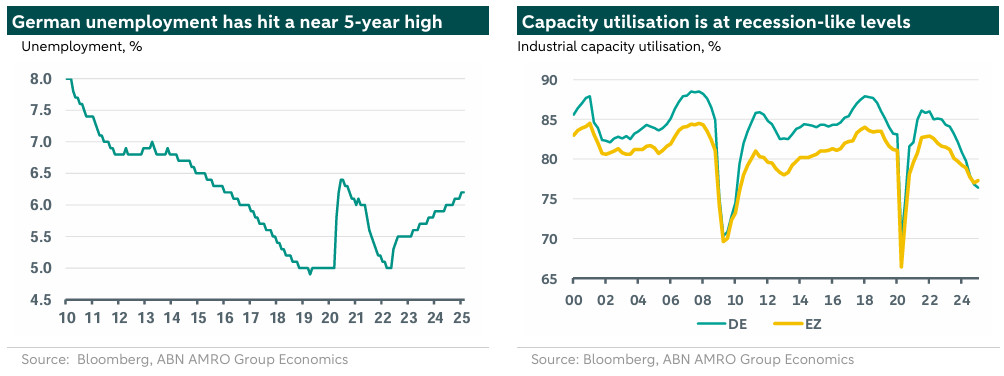

Finally, the fiscal multiplier will also depend on the degree – and composition – of slack in the economy. The literature suggests that a greater degree of slack tends to raise the multiplier. Noteworthy here is that European industry, particularly in Germany, has significant spare capacity. Unemployment in Germany has risen to a near 5-year high of 6.2%, and there is likely much more ‘hidden’ unemployment than suggested by the labour market data alone, with capacity utilisation at levels normally consistent with recession. There is of course a question mark over how much of this spare capacity can be quickly re-tooled to the production of defence equipment. Much of the spare capacity right now is in the beleaguered car industry. Rheinmetall, , has suggested taking over VW’s Osnabrück plant to make tanks, while defence electronics company Hensoldt is in discussions to take on 200 auto part workers from Bosch and Continental. The quicker the retooling of the economy can take place, the lower the reliance on imports, and the bigger the gains for productivity. But there is naturally a lot of uncertainty around this.

Indicative base case: A significant spending increase with a gradually rising multiplier

We judge that the political momentum is sufficient for a major ramp up of spending over the coming years. While there will inevitably be leaders and laggards in spending, a reasonable middle ground scenario would see enough of a boost among the leaders – especially Germany – to drive a rise in defence spending to 2.7% of eurozone GDP by the end of 2026 (the average for the year is likely to come in lower than this). Initially, we expect the multiplier to be on the low side – similar to what has likely been the case in Poland at c0.2-0.3 – but that this picks up relatively quickly given: a) the significant slack in eurozone (and especially German) industry, and b) the political will to procure much more defence equipment within the EU. By the end of 2026, we therefore assume the multiplier will rise to the lower end of estimates seen in the US, of around 0.5-0.6.

What does this mean for the growth outlook? All else equal – a bold assumption at present, given the looming threat of much bigger US tariffs – we expect 2026 eurozone growth to see a lift of around 0.3pp from defence spending alone. When including German infrastructure spending, this could be as high as 0.5pp assuming spillover effects. For 2025, we expect a negligible impact due to high initial import intensity, and because spending will take time to get going. In terms of the quarterly growth trajectory, we expect outlays to start to increase from Q3 2025 onwards, reaching a cruising speed by Q2 2026. Given a gradually rising multiplier, this means the peak growth impact is likely to come around mid-late 2026, with between 0.1-0.2pp additional q/q growth. Looking beyond our forecast horizon to end 2026, potential growth may even see a lift from R&D and productivity spillovers – up to 0.25% per 1% of GDP increase in spending according to the balance of the academic literature.

What about inflation and the ECB?

Our current base case currently sees inflation falling below the ECB’s 2% target by early 2026, driven largely by the negative drag from tariffs on global trade, and the growth hit from lower exports to the US. Higher defence spending by itself is likely to blunt that downward pressure on inflation, but we think it is unlikely to be a significant source of upward inflationary pressure. First, because much of the initial spending will go on imports, and second, because even as domestic spending ramps up, it will be entering an economy with a lot of spare capacity in industry. Under our current US tariff scenario, we would expect higher defence spending to lead to somewhat less downward pressure on core inflation than would otherwise have materialised towards the end of 2026 and moving into 2027. Inflation would still however be broadly around the ECB’s 2% target at this time. In this scenario, given that the growth picture is also more solid, we think the Governing Council would end rate cuts around 50bp higher than our current base case, at 1.5% in the deposit rate – our own estimate of neutral. This hinges, however, on our current tariff view. We will do a full review of our base case – incorporating defence spending impact estimates – following the 2 April tariff announcement from the US.

The Netherlands: Political division likely prevents a sharp increase in spending

Despite having more fiscal leeway compared to other eurozone countries, political division in the Netherlands will likely prevent a big surge in spending on the short-term. Among the four coalition parties, the VVD supports raising the defence budget to 3.5% of GDP, but the other three remain sceptical. The PVV has stated they first want to see funding go to enhancing households’ purchasing power, such as reducing energy bills and rents. Similarly, the NSC and BBB argue that more budget should be allocated to increasing purchasing power, implying it is still difficult to allocate more money to defence.

As discussions for the Spring Budget – which encompasses the government’s budgetary negotiations – have commenced, the coalition faces tough decisions. Although the estimated budget deficit for 2025 has been reduced and the starting point of public finances is strong, the necessary expenditures and desires seem to be greater than the structural budget allows*.

* The outlook for public finances suggests further deterioration, with higher budget deficits and an increasing debt ratio. For long-term fiscal sustainability, the Budgetary Framework Study Group recommends reducing the structural budget deficit to 2% of GDP, which requires improving the revenue and expenditure balance.

Debates around the common EU fund have also been ongoing, with the Netherlands traditionally opposing shared debt for new EU instruments such as Eurobonds. After many discussions and disagreements, the most of their concerns on the EUR 800bn EU defence plan last Tuesday. Likely, some of the and purpose of the fund will remain intact.

Impact on the Dutch economy

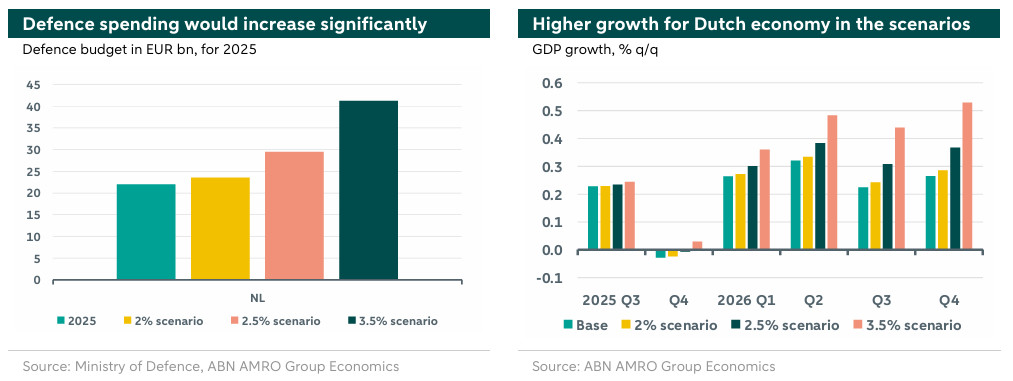

According to NATO data, the Netherlands met its target in 2024, but an unanticipated rise in GDP caused actual spending to fall just below the 2% target. The coalition aims to meet the 2% NATO target and has increased the defence budget structurally. The that due to the increased focus on defence by the previous and current cabinet, spending is already expected to rise in the coming years. Still, with our growth forecasts for 2025, the current EUR 22bn budget falls short of the NATO target, at 1.87% of GDP.

The tight labour market has resulted in significant underspending by the government, creating about realizing defence spending increases as it could also simply lead to higher underspending. , the goal to expand defence personnel by 9,000 annually fell short, reaching only 4,200 in 2024, mainly due to limited training capacity despite high application numbers.

Moreover, much of the recent defence procurement happened outside the EU. The Netherlands is particularly reliant on the US, accounting for 97% of total defence imports. As is the case for the broader eurozone, this dependence dampens the potential impact of increased defence spending on growth – i.e. the size of the fiscal multiplier – in the short term. But over time, as the industrial defence capacity increases, the boost to the economy would accelerate.

For the Netherlands, we assume the multiplier gradually rises to 0.5%, which is somewhat lower than what we assume for the broader eurozone. This is due to the limited slack in the economy (as illustrated by the positive output gap) and the tight labour market. Also, while calling for scaling up factory lines in the bloc, Dutch defence that he is also open to buy weapons outside of Europe. Still, the capacity utilisation in the industrial sector is low, but the question remains how much of this spare capacity could be quickly re-tooled to produce defence equipment. In line with the broader EU, we assume a gradually rising multiplier.

Considering political division and labour market constraints, we judge that currently the most realistic scenario would be a defence spending increase to 2.5% of GDP by end 2026. All else equal, this would leave our growth forecast for 2025 largely unchanged, while increasing our 2026 forecast by 0.2pp. The magnitude and timing largely depend on our assumptions, such as how quickly import dependency is reduced and how the spending is financed. The downside scenario assumes meeting the 2% NATO target by end 2026, having a minimal impact on growth as it's mostly factored into our existing forecasts. Conversely, in the upside scenario where defence spending climbs to 3.5% of GDP by end 2026, growth could rise by 0.4pp in 2026. As explained above, on the long term, increased defence spending may lead to productivity spillovers.