Less room for offsetting for small-scale solar generation

The Netherlands has ambitious targets for reducing CO2 emissions. The build-up of solar energy capacity plays an important role in this. Solar panels on homes generate 40% of solar energy. The net-metering scheme has stimulated small-scale solar energy generation. The government wants to phase out the net-metering scheme over the next few years. This may affect small-scale solar power generation. Home batteries and the deployment of electric cars could provide a solution.

Introduction

The Netherlands aims to reduce CO2 emissions by at least 55% from 1990 levels by 2030 and to cut them completely by 2050. This requires that the share of renewable energy increases dramatically. Besides onshore wind, offshore wind and biomass, solar energy is an important source of renewable energy. Solar energy requires solar panels and an inverter. An inverter converts the direct current generated via solar panels into usable alternating current for the households. The energy flows into the home's electricity grid via this route. Solar power generation is also known as solar PV.

Solar PV target

The target for renewable energy (offshore and onshore) for 2030 was 84 Terawatt Hour (TWh) in the 2019 climate agreement signed by companies and the government. The target for wind on sea was 49 TWh and for solar and wind on land 35 TWh. This target was revised upwards to 120 TWh in the 2021 coalition agreement. In 2021, the share of renewable electricity in total electricity consumption was 33.8% of the 121,8 TWh or 41,2 TWh. Currently the share of solar PV is 9.3% of the total is around 11,3 TWh.

The Climate Accord agreed that efforts by decentralised authorities leading to more than the estimated 7 TWh of small-scale solar generation (such as local incentive schemes) count towards the task of achieving 55% reduction. In a letter to the House of Representatives, the Minister for Climate and Energy indicated that due to the tightened CO2 reduction target of 55%, he would recalibrate the target of 35 TWh of renewable electricity production on land (solar and wind).

Small-scale generation of solar energy

Solar energy can be generated in small-scale projects with a net-metering scheme, large projects that do not receive subsidies from the sustainable energy production incentive scheme (SDE(++)), and large projects that do receive subsidies from the SDE(++) scheme. The net-metering scheme was established in 2004 to encourage investment in solar panels by homeowners. The electricity that solar panel owners do not directly use themselves, they feed back to their supplier. They can offset this electricity - measured over a calendar year - against the electricity they buy. As a result of the net-metering scheme, the price sold the electricity delivered back to the supplier is as high as the price the small-scale consumer pays for the electricity he buys from the supplier. In addition, taxes and costs for supply and storage of renewable energy do not need to be paid on the electricity supplied back to the supplier.

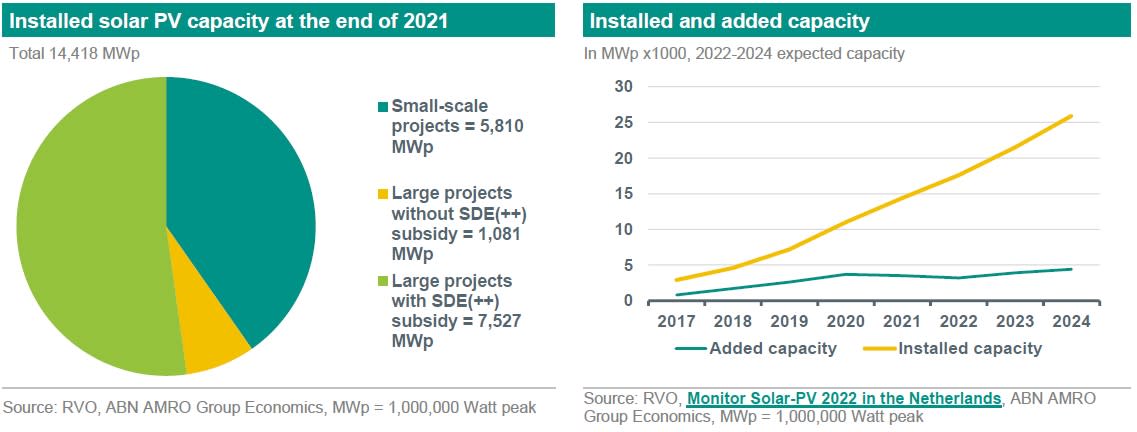

In 2021, solar power's share of total electricity consumption was 9.3%. A total of 14,418 MegaWatt peak (MWp) of solar PV capacity was generated. Of this, 5,810 MWp was from small-scale projects (smaller than 15 KWp) with net-metering and other schemes. This is equivalent to about 4.7 TWh in 2030 .The climate agreement assumes that small-scale solar PV generation will grow to 7 TWh in 2030. Over the past two years, this increased by about 1,100 to 1,200 MWp per year (around 1 TWh). This has yet to be recalibrated to the 2021 coalition agreement where the CO2 reduction target has been raised from 49% to at least 55%.

The majority of solar energy generated via small-scale projects comes from solar panels on homes (96%). The number of homes with solar panels is growing rapidly. By the end of 2022, 2 million homes had solar panels compared to 1.5 million in 2021. In 2021, 35% of owner-occupied houses and 16% of social housing properties had solar panels. The average maximum power per solar panel is currently 400 Wp. However, there are also solar panels of 500 Wp, although these tend to be more expensive and larger, which means fewer can be installed on a roof. A 400 Wp solar panel produces about 340 kWh per year. The conversion factor of 0.85 is based on the number of sunlight hours and light intensity.

Phasing out of the net-metering scheme

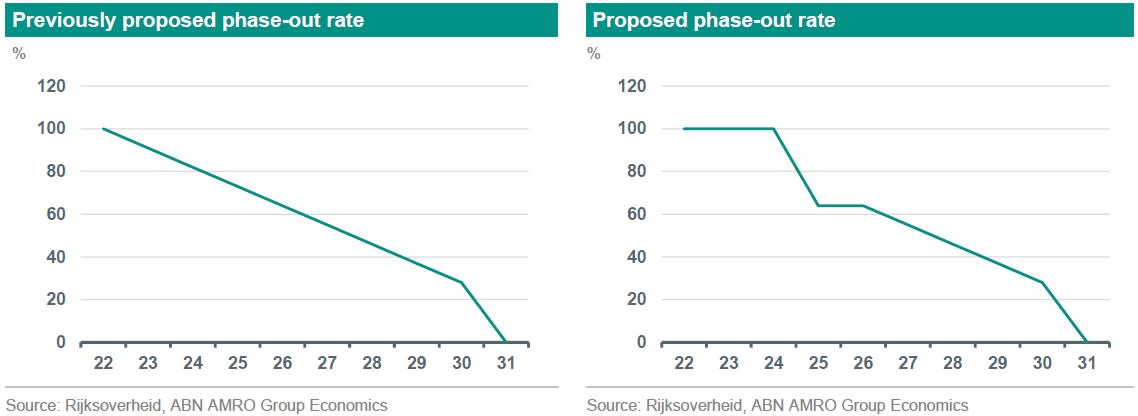

On 17 January, the House of Representatives had a plenary session on Minister Jetten's proposal to phase out the net-metering scheme from 2025. Earlier, the idea was to reduce the net-metering from 2023. This is now likely to become 2025. From then on, only 64% of the electricity supplied back may be netted (see chart below). Energy tax and supply costs will have to be paid on the part that is not netted. After 2025, the scope for balancing will be further reduced to ultimately zero in 2031. The reduction of the balancing percentage to 64% in 2025 means that a household supplying 2,000 kWh back to the grid will only be allowed to balance 1,280 kWh (while currently the 2,000 kWh is allowed to be balanced) . On the remainder of the 720 kWh feed-in it will receive a fee from the supplier on which energy tax must be paid.

What are the reasons for phasing out netting?

The net-metering scheme has caused solar panels on homes and small-scale solar energy production to increase significantly. Nevertheless, the minister wants to phase out the net-metering scheme. To this end, he cites the following reasons. First, the sharp decrease in payback time. A TNO analysis shows that the payback time of 10 solar panels purchased in 2022 is 5 years. Should netting be phased out as per the proposal, the payback period will increase to around 7 years. This assumes an average investment cost of EUR 1.20 per Wp. This Wp price is currently EUR 1.85, a considerable increase. This probably already ensures a longer payback period. But the current high energy prices make solar panels attractive again.

Secondly, the net-metering scheme does not encourage small consumers to use their own generated solar energy, or to store it. With the growth of renewably generated power, the supply of power fluctuates widely during the day, peaking during early afternoon. Due to the extensive supply, the spot price of energy is then at a low level. The current net-metering scheme removes the incentive to use appliances in the home at that time, or to store currently generated energy in a battery for use at a later time. Instead, power is fed back, which can overload the grid. Expanding the grid to prevent overloading requires substantial investment.

Should net-metering be phased out, this is likely to weigh on the demand for solar panels. In recent years, added capacity increased by 1,100 to 1,200 MWp. The energy crisis and higher energy costs have further increased the demand for solar panels. Due to the lack of qualified personnel, the demanded capacity has not yet been fully added. This will probably still happen in the first half of 2023, so that the added capacity will continue to increase significantly. However, once the decision to reduce the scope for offsetting becomes a reality, fewer households are likely to have solar panels installed.

Still, there are bright spots. The government could encourage the purchase of home batteries. These are currently expensive to buy, but can help prevent peak loads on the grid. What does a home battery do? Part of the energy generated by solar panels is consumed. The part that is not consumed is stored in the home battery. Only when the battery is full, power is fed back into the grid. The energy stored in the home battery can be used when it is dark, or on days when less energy can be generated. Depending on the storage capacity, a home battery can bridge one or several days. Unfortunately, home batteries are pricey to buy for the time being. A possible alternative is to use the electric car as temporary storage. Currently, it is not yet possible to use the energy charged in an electric car battery back in homes. But developments are currently going very fast, so such a trajectory is in sight.

Conclusion

In the coalition agreement, the Netherlands has revised upwards its targets for CO2 reduction and the share of renewable energy in the energy mix. Solar panels are an important way to generate energy. Thanks to the net-metering scheme, small-scale solar energy generation has increased significantly. Small-scale solar energy generation accounted for about 40 per cent of all energy generated by solar panels in 2021. Scaling down the energy-saving scheme, which is what the government now wants, could put a brake on the expansion of small-scale solar power generation. This could make it harder to meet climate targets. Alternatively, the change could be accompanied by incentives for home batteries and the use of electric cars as home batteries, allowing the growth of solar power generation from small-scale projects to continue.

This article is part of the SustainaWeekly of 23 January 2023