Is the Fed tightening into a recession?

The Fed is widely expected to raise rates another 75bp this week, even as the data might show the US is in a technical recession. While we expect a recession to be declared over the coming year, a downturn alone will not be enough to stay the Fed's hand. Rather, 'convincing evidence' will be needed that inflation is coming back to target.

FOMC Preview: A 75bp rate hike is more likely than 100

This coming Wednesday, the FOMC is widely expected to raise the target range for the fed funds rate by 75bp, taking the upper bound to 2.5%. Following a hotter-than-expected reading, money markets briefly toyed with the prospect of a 100bp move, but the probability of this has since been largely priced out following pushback from notable hawks on the Committee. Indeed, the data flow since the CPI reading has been mixed, at best; retail sales surprised somewhat to the upside but were essentially flat once adjusted for inflation, while housing market and survey data for both manufacturing and services pointed to a significant cooling in the economy (see below). To be clear, the Fed is still on an aggressive tightening path to restrictive policy territory, given the continued upside risks to the inflation outlook, but a 75bp move is already quite consistent with a historically rapid tightening pace. Assuming the long-run nominal neutral policy rate is c.2.5%, policy will already be in restrictive territory by September – a dramatic turn-around from the ultra accommodative policy stance as recently as March.

Forward guidance is likely to become more equivocal…

While Fed Chair Powell is likely to remain steadfastly hawkish in the press conference on Wednesday, we think the recent mixed tone to the macro data – and the fact that rates will no longer be so accommodative – might herald a shift in Fed communication at this meeting. from the ECB last week, we expect Powell to refrain from making explicit commitments to specific-sized policy moves at coming meetings, although he will continue to reaffirm the Fed’s commitment to raising rates until the Committee sees ‘convincing evidence’ that inflation is coming back to target. By ‘convincing evidence’, we interpret this to mean a string of monthly (as opposed to year-over-year) core inflation readings consistent with 2% inflation – i.e. c.0.2% m/m rises (for reference, the most recent core CPI reading was more than three times that pace, at 0.7%).

...but the Fed will be patient in its inflation fight

We do not expect core inflation readings like this until early 2023, although headline inflation could well already be peaking given that a range of pipeline pressures – notably non-energy commodity prices, and broader supply-side bottlenecks – have . With wage growth cooling, and the economy slowing, this will ultimately feed through to services inflation. However, until that actually happens the Fed will be in no hurry to declare victory in its inflation fight. As former NY Fed president Bill Dudley recently remarked, the Fed will be keen to avoid the ‘stop-go’ pattern of policy tightening of the 1970s, when the Fed persistently underestimated the stubbornness of inflation over a number of years, leading to wild swings in interest rates. This ultimately required the much more painful medicine of Paul Volcker to finally bring inflation under control in the 1980s. This is why Chair Powell has been open in saying that the risk of persistent inflation is a bigger risk than that of recession, and as such, a recession by itself will not be enough to put an end to policy tightening.

Given this, although we think forward guidance is likely to become more vague, we expect the Fed to continue to hike rates aggressively following the 75bp move on Wednesday. Our base case remains for 50bp moves in September and November, followed by 25bp moves in December and February – taking the upper bound of the fed funds rate to 4%, where we expect it to peak.

Is the economy already in a recession? Probably not

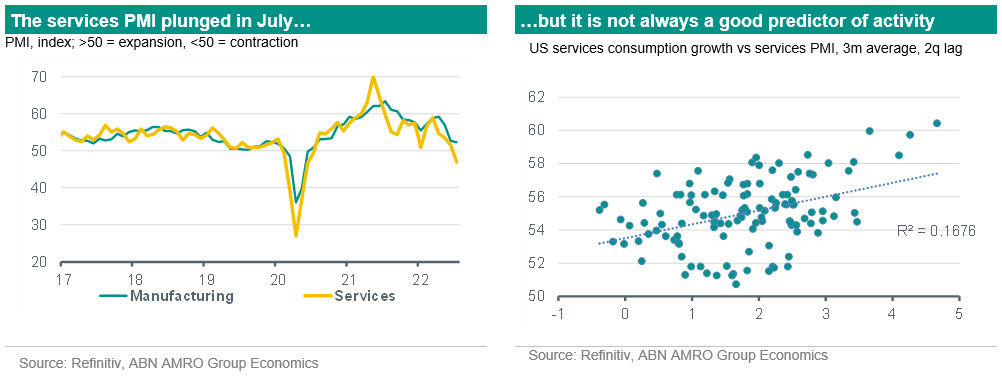

Last Friday, the flash services PMI for July surprised sharply to the downside, falling to 47 from 52.7 in June, and suggesting the services sector – which makes up over 70% of the economy – is in contraction mode. This comes just as Q2 GDP data – due out this Thursday – might suggest the economy has already been in a technical recession (defined as two consecutive quarterly declines in output), at least judging from the from the Atlanta Fed; as of last Tuesday, this stood at -1.6% q/q annualised. Indeed, we judge uncertainty in GDP forecasts to be particularly high in the post-pandemic period, chiefly due to supply side strains, and the consequent swings we have seen in net exports and inventories. Despite the strength in underlying demand in the US, these swings were big enough to cause a contraction in the economy in Q1. However, even if the economy has been in a technical recession, it is very unlikely that the business cycle dating committee of the NBER – the official arbiter of recessions in the US – will declare one. This is because the NBER judges recessions based on a much broader set of data, including the labour market and underlying demand (consumption and investment). Taking this broader definition – and given the strength in the labour market and in consumption growth – it would be hard to conclude that the US has been in a recession.

But a recession is likely in the next 12 months, according to the official (NBER) definition

The weak PMI reading for the services sector is probably a warning sign of things to come, but we would not read too much into this particular month’s reading. First, the services PMI is not a very reliable predictor of services consumption, let alone GDP, and we note that the more forward-looking sub-components of the report were still signalling expansion. Second, the services PMI has in the past fallen sharply in one particular month, only to rapidly bounce back – most recently, this happened in January of this year. As such, it is possible that the July reading was an anomaly. With that said, in big picture terms we do expect a significant weakening in the economy in the next 12 months, as the hit to real incomes from high inflation leads to outright declines in goods consumption, while the rise in interest rates weighs on investment and the housing sector. Over time we expect this to drive a turnaround in the labour market, with unemployment expected to begin rising in Q4, picking up to c.5% by the end of 2023, up from 3.6% at present. Such a move is likely to meet the NBER definition of recession, with an announcement perhaps coming in early 2023.