Housing market picks up, making the house sustainable more expensive

Prices and transactions are increasing faster than expected: estimates revised upwards. Wage increases and decline in mortgage rates improve purchasing sentiment. New coalition mainly maintains course set by previous minister Hugo De Jonge. The few new coalition proposals are barely outlined.

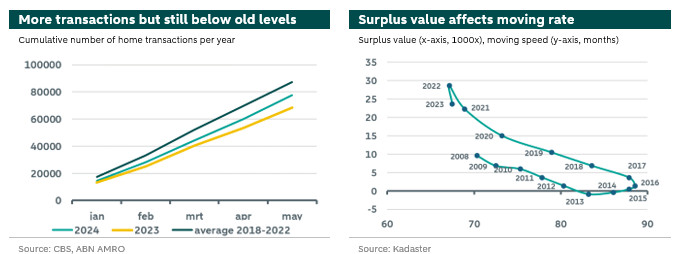

More transactions...

The housing market is picking up, so we are raising our transaction forecast for 2024 from +0.5% to +10% (201,000 transactions). For 2025 we are lowering our estimate from +3% to +2.5% (206,000 transactions).

Increase in transactions is mainly driven by first-time buyers and exiting landlords. Almost 78,000 existing homes were purchased in the first five months of this year, 9,000 more than in the same period last year and almost as many as in 2022. The increase in home purchases was partly driven by the increase in the NHG limit on Jan 1 this year. Especially first-time buyers, , benefit from this increase as it improves buying conditions. In addition, in response to the and other measures that make home rentals less attractive. Consequently, transactions of apartments, a category in which there are most rentals, are rising the most.

Patient sellers also see their opportunity. Many sitting homeowners waited to sell last year because of increased mortgage interest rates and the price dip. Instead of moving, homeowners often chose to stay in their homes and renovated if necessary. Now that mortgage rates are coming down and home prices are rebounding, enthusiasm is growing to take the plunge into the next home. With increasing surplus value, the difference between home market value and initial purchasing price, . Overall, the sharp increase in the number of transactions in the first five months of this year gives us reason to adjust our forecast. However, we are not yet going all the way back to pre-energy crisis average.

...and higher prices

At the same time, we are also increasing our price forecast from +6% to +7.5% for 2024. For 2025 we keep our forecast constant at +5%.

Home prices are near record highs, but not everywhere. In May, the CBS/land registry house price index was 8.7% above last year’s level. The average purchase price reached EUR 445,000. This implies a reversal of the 2023 price drop and valuations are back at record levels. The national realtors association (NVM) speaks of a . However, there are considerable price differences between the various provinces and energy labels also plays an important role these days. The more favourable the energy label, the higher the valuation. The are also gradually getting more when valuing homes.

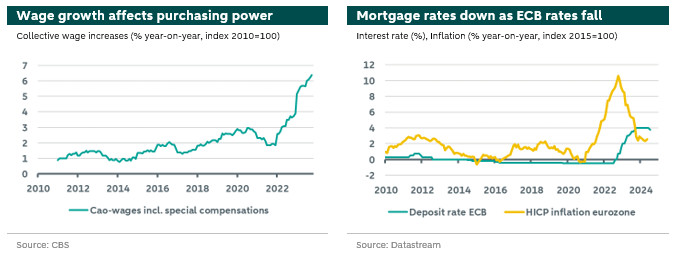

Wage increases lead to higher borrowing capacity, stimulating demand. Wages are rising fast and are expected to continue to do so in the short-run. The main reason is a tight labour market, allowing workers to command wage increases. Recent show this. Due to the wage growth, homebuyers can borrow more money, translating into increasing demand and (with limited supply) higher home prices. We estimate that recent wage growth has not yet been fully reflected in house prices, in part because many collective bargaining adjustments do not take effect until July or later this year. Moreover, we take into account that collective bargaining outcomes will continue to be higher than usual for the rest of this year and in 2025. This reinforces our expectation that house price appreciation will continue for the foreseeable future.

Lower mortgage rates drive up prices through cheaper borrowing. The European Central Bank (ECB) recently cut interest rates for the first time. We expect more interest rate cuts to follow, as current interest rates are slowing down the European economy, while the need to tame the economy fades into the background. Currently, inflation is moving back toward the 2% target, allowing the ECB to stand still. Further interest rate adjustments are therefore on the horizon. We think the so-called deposit rate, now at 3.75%, will fall to 1.5% in the second half of 2025. Lower ECB interest rates will push down longer-maturity interest rates in financial markets. The 10-year rate on Dutch government bonds is projected to fall from 2.75% now to 2% by the end of next year, according to our forecasts. In this forecast scenario mortgage rates will also come down.

Buyers confidence has rebounded, but affordability remains an issue. As incomes rise and inflation returns to moderate levels, consumer sentiment improves. Private households get more clarity about their future spending when inflation is low. This eases financial planning and contributes to their willingness to make long-term consumption decisions, such as buying a home. This is reflected in the sub-index of the consumer confidence and the market indicator of the home ownership association. Both indicators are not yet at pre-energy crisis heights though, indicating some consumer uncertainty. Among other, we attribute this uncertainty to the fact that owning property has become unaffordable for a large group. An average home now requires a gross income of , more than twice the mode. International comparison shows the Dutch housing market to be . Those who want a chance to buy a home must have a surplus value on their current home or considerable savings. Fortunately, many households have these financial buffers. CBS figures show that homeowners have a lot and that households have . In the second quarter of 2024, first-time buyers without surplus value put an average of about in equity on the table buying a home.

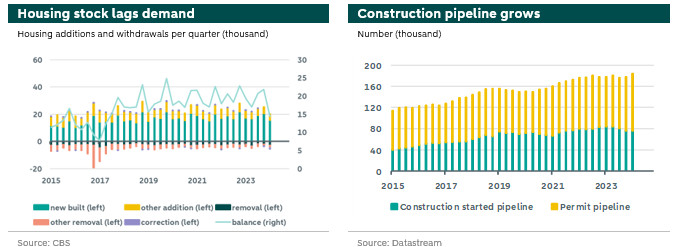

On the supply side, tightness remains due to bottlenecks in construction. Unfortunately, new construction has lagged in recent years. The outlook for the next few years is not particularly favourable either. In the first four months of the year, 22,000 new homes were built. If this trend continues, the annual total ends up at 73,000 new homes. But that is a very optimistic estimate. To reach the annual target of 100,000 housing units, a lot of offices and stores will have to be , houses will have to be split, etc.. This is very ambitious and in recent years, the number of homes added to the housing stock in this way has been significantly lower.

Building permits offer hope, if they are used. As a silver lining more building permits have been issued this year. At the current trend, the number of permits issued this year will be a quarter higher than in 2023. The issuance of more permits is a first step toward construction start and eventual realization, but this does not mean that the flag can be raised yet. There is a risk that planned homes will remain in the for longer, given all the obstacles in the sector. The list of obstacles to new construction is long. Consider the shortage of construction workers and the limited capacity of the electricity and drinking water networks, which prevent homes from being connected to crucial utilities. There are also soil and water quality deficiencies, which can create new problems, and objection procedures from local residents, delaying plans.

Ultimately, landowners decide whether affordable housing will be built. are less eager to sell their land for the realization of affordable housing because they will make less profit. Rather, they often dedicate themselves to the realization of owner-occupied and private rental housing for which the returns are higher. As far as social housing is added, it is mainly built by housing corporations. But they have invested much less in land positions since the financial crisis. They have also cut back on their development departments. Corporations have put new construction on the back burner because they could no longer finance the construction of social housing with profits from the construction of owner-occupied and free-sector rental housing. The idea behind this restriction is that there should be a free playing field and that corporations should not have a competitive advantage over other market players due to their access to subsidies.

De Jonge's goal: more freedom for corporations and room for new housing. To spur the lagging construction of affordable housing by corporations, previous housing minister De Jonge wanted to relax the restrictive rules for corporations. To do so, he needed permission from Brussels, something he fought for until the resignation of the outgoing cabinet. In other areas, too, De Jonge persevered stubbornly. Meanwhile, the Senate has passed his Affordable Rent Act and De Jonge has designated six new areas as suitable for large-scale housing construction after 2030, the year when-if all goes well-the "million more homes" goal will have been achieved and the current shortfall will have been made up.

Coalition agreement: new coalition sticks to old course…

The new coalition is essentially sticking to all initiatives started by De Jonge. In line with previous plans, there will be a coordinating minister for the housing dossier. Nothing will change regarding the tax treatment of owner-occupied housing. Mortgage interest deduction, owner-occupied home forfeit and the Hillen regulations will all remain intact. Nor will the Affordable Rent Act be touched upon. In addition, the target of adding 100,000 homes per year remains intact, as does the governments greater directorial role. The coalition also remains committed to the transformation of stores and offices and to better utilization of the housing stock by means of house splitting.

The coalition agreement reads more like a statement of intent than a concrete list of measures. The coalition wants new construction to pay more attention to focus groups, such as the elderly and first-time buyers, just like De Jonge. But it is unclear what measures the coalition has in mind in this regard. In general, it is unclear for nearly all housing related plans how the coalition wants to reach its targets. The question often remains: how? One example is the nitrogen limitation. The coalition wants to get rid of it, but it is unclear how it intends to do so. Many of the intentions are ambitious, but lack detail. With all the implementation problems that already exist, we fear that there is a good chance that it will remain just plans.

...with a few adjustments ...

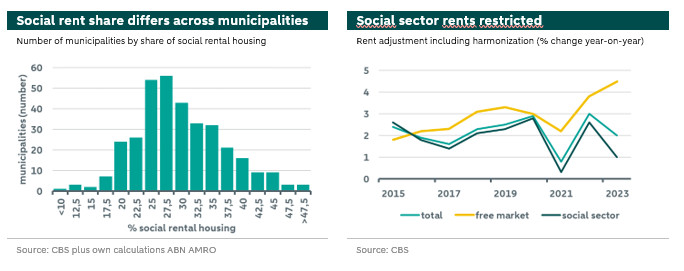

The requirement of 30% social housing per municipality will be weakened. The requirement will no longer be considered at the municipality level, but at a transcending area level. The reason is that the stock of social rental housing is unevenly distributed among municipalities. If the rule is applied strictly, only social housing would be allowed to be added in some, wealthy municipalities. On paper this sounds sympathetic, but in practice it is difficult to implement. Given high land prices, the desired social housing could only come about if substantial subsidies are granted. A number of projects would have to go back to the drawing board. This is a risk, because it leads to delays, postponement and possibly even abandonment of previously initiated housing projects. This obstacle is removed by looking at places for social rental housing not at the municipality level, but at the wider area level.

Involved parties are encouraged to make more construction agreements. There is an adjustment at the so-called residential summits where all parties involved come together to make agreements on housing to be built. The agreements will be made enforceable, making them more committal than before. The adjustment is necessary because although many commitments were previously made, by no means all of them were fulfilled. Whether the change will also lead to more housing remains to be seen, because if agreements become enforceable, involved parties will be less likely to make commitments. For example, pension funds will not make firm commitments when they bite with their return requirements. Plans such as encouraging pension funds to generally invest more in housing lack legal requirements in our view and are therefore questionable.

Social rent increases from 2026 will be linked to inflation, with no premium: CPI + 0%. Currently, social rent is not linked to inflation, but to collective bargaining wages. The linkage was temporarily changed because of high inflation during the energy crisis. Assuming that inflation will fall to 2%, it is likely that rent increases in the coming years will be lower than under a collective agreement-based indexation. This will be a relief for sitting tenants. Investors and corporations, on the other hand, will be less pleased, as the measure will depress their income. If this results in less investment in new rental housing, it will make it harder for future tenants to find housing. In this sense, the measure implies a trade-off between the interests of future versus current renters.

The decentralized construction approach for small-scale projects seems promising, but raises questions. The coalition agreement mentions "adding a street”. This decentralized, small-scale approach should lead to more building sites and housing, according to . This is good news because more housing is needed to solve the housing shortage. Still, it is good to consider the possible consequences of 'adding a street'. It may have the effect of putting quantity before quality and creating new homes in locations where there is little demand for housing, or where housing development is degrading the environment. It could also result in housing near roads, in locations that do not fit within the GGD's noise and particulate matter guidelines. Already, those guidelines regularly appear to get snowed under in the push for more housing. Finally, a practical point. 'adding a street' means that there will be more small projects that need municipal guidance. That means more work for municipal officials, of whom there is already a severe shortage.

The coalition is considering a plan benefit tax and a land tax. Most notable are the proposals for . The plan benefit tax was already on the previous government’s list of alternatives, but a land tax is a new idea. A plan benefit tax is a tax on the difference in value of land on which construction is allowed and the value of the land at the previous function, such as agriculture. This tax pushes down the price of land and can generate revenue for municipalities for housing or other purposes. This can give municipalities an additional incentive to encourage housing development. A land tax can be a levy on both developed and undeveloped land. If the goal is to accelerate housing projects that just don't get going, it is better to tax only undeveloped land with residential zoning, because such a tax penalizes construction delays.

... at the expense of climate policy.

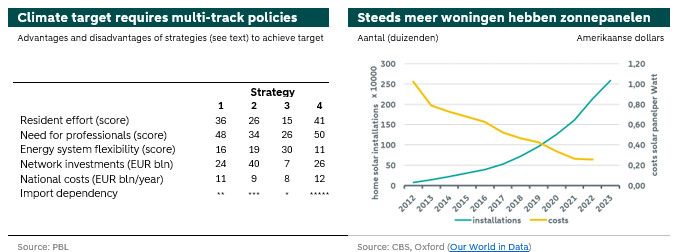

The coalition agreement contains no measures that help move closer to the climate goals for the built environment or get homes off the gas. Broadly speaking, there are four ways to do this: by (1) reducing energy consumption through home insulation; (2) heating buildings using heat networks; (3) using clean gas; and (4) switching entirely to solar and wind-generated electricity. A good analysis of all the pros and cons of these four options was recently presented by the

Sustainability measures are cut and electrification is given less priority. The coalition is not allocating additional money to solve congestion problems of the electricity grid. It is also cutting back on SDE++ subsidies for the rollout of distance heating networks and on municipal subsidies to make homes with a poor energy label more sustainable. Furthermore, the coalition will let go of the mandatory implementation of heat pumps, so that the incentive to choose the most sustainable option during renovations will decrease. It further lowers this incentive by keeping gas affordable. The coalition justifies this with the argument of guaranteeing energy supply. That is a noble goal. But in doing so, it shows above all that it has an eye for the short rather than the long term. The long-term security of existence of households actually decreases if they remain dependent on gas.

Abolition of net-metering leads to lower financial returns and longer payback periods. The coalition has decided to abolish the net-metering scheme at the end of 2026 all at once instead of choosing a gradual exit over a period of 4 to 5 years, as originally intended. Homeowners with solar panels will have to adjust their financial calculations because of this measure. The net-metering scheme allows households to use 100% of the solar electricity produced because it is compared with consumption over the year. Depending on behaviour, we estimate that without a net-metering scheme, households can only use 30-50% of the generated electricity. Consequentially, the payback period of solar panel investments without a net-metering scheme becomes 2-3 times longer. For example, if households expected a payback period of 5 years, it becomes 10 to 15 years. Vice versa, the annual return drops from 20% to 10% - 6.7%.

The change stimulates demand for home batteries, although investment in them does not make up for investors loss. We expect that the abolition of the net-metering scheme will encourage households to invest in battery solutions in the upcoming years. By storing surplus electricity locally in home batteries, 50-70% of the generated solar electricity can be used. This makes the payback period only 2 to 1.5 times longer than under the net-metering scheme. However, home battery cost are currently comparable to those of solar panels, resulting in doubling the required investments. Nevertheless, this can be a good investment. However, there are also some practical problems to solve. For example, home batteries are large, on average comparable to a refrigerator. This is especially a problem for smaller homes, as crawl spaces are often unsuitable for storage because of moisture. Another problem is that the households still rely on electricity from the grid in the winter.