Housing market - Market rebounds thanks to lower interest rates and rising income growth

The house price index rises and is almost back to the record level of July 2022. Lack of houses for sale and lagging new construction put a brake on transactions. Private landlords are starting to dispose of homes, creating opportunities for first-time buyers. A climate label could help improve assessment of climate risks associated to houses.

Economic sentiment is improving again. The sharp rise in inflation after Russia's invasion of Ukraine was contained relatively smoothly and, despite the sharp interest rate hikes implemented by central banks to curb inflation, economic activity is keeping up. After the lockdowns in the fight against the pandemic, this time the economy proved resilient to an energy price shock. Regularly downturns are caused by demand slumps. But in the past two crises, supply issues were the problem, complicating the analysis of the economic impact and deciding on appropriate countermeasures. For the second time in a row, we can note that the disruptions turned out to be less severe than feared, that the economy remained resilient and, thanks in part to the alert action of governments and central banks, is recovering relatively quickly. Central banks are preparing to cut interest rates and workers are seeing their wages rise sharply, contributing to the affordability of the housing market. Relief over the resilience of the economy and the prospect of interest rate cuts is manifesting itself in equity market and house price increases. We are raising our house price estimates for this year from 4% to 6% and for next year from 3.5% to 5%.

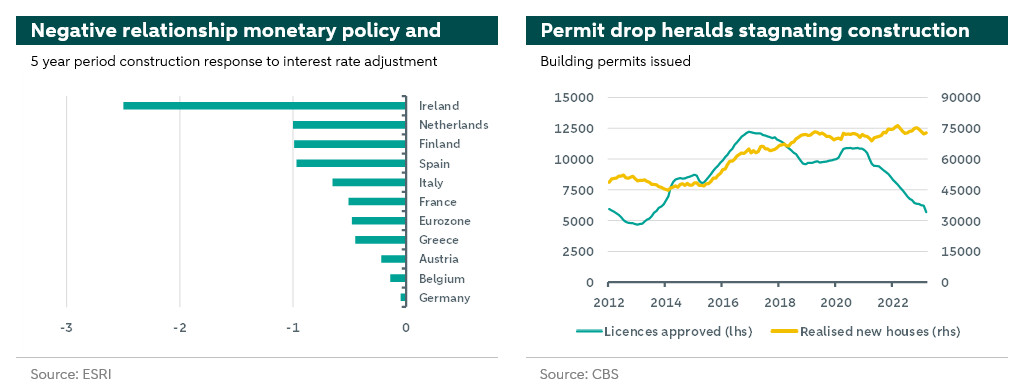

The number of transactions is also on the rise. In the first two months of this year, significantly more homes changed hands than in the same two months last year. The widening of the first-time buyer transaction tax exemption and the increase in the NHG cost limit play a role in this. Furthermore, slightly more newly built houses were sold, which contributed to temporary push to existing house transactions. Temporary, as the number of housing completions lags behind targets. This is due to problems in housing construction. Compared to other countries, construction activity in the Netherlands is very sensitive to interest rate fluctuations. Given the low number of building permits issued, the number of housing completions will remain modest for the time being. And once started, construction projects sometimes cannot be delivered because of problems with energy grid congestion. A recovery of transactions towards pre-energy crisis levels is therefore not likely, even if the latest signals are quite favourable. Housing transactions do get a boost from landlords disposing of rental properties. House rental have become less attractive due to increased interest rates, tax changes and impending rent control measures. On balance, we see no reason to adjust transaction estimates. We stick to our projections of +0.5% this year and +3% next year, amounting to 183,000 transactions this year and 189,000 next year.

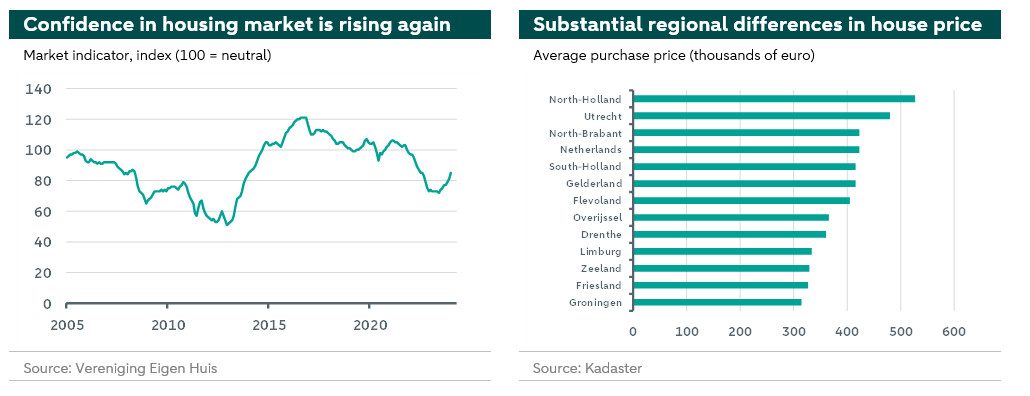

Sentiment towards the housing market improves

Pessimism regarding the Dutch housing market is gradually ebbing away. Vereniging Eigen Huis' reached a value of 85 according to the latest reading in January. That is still below the neutral level of 100, but clearly higher than last June's low of 72. Buyers rate overall economic conditions and their own financial situation more positively. But it is the improved interest rate outlook that is contributing to the return of confidence.

The improvement in housing market sentiment is reflected in a recovery in house prices. The CBS/Kadaster has been rising monthly since May 2023, after about a year of declines. Thanks to price increases, the price index was already 5.8% above last May's level in February. The index is still only 0.8% below its July 2022 peak. The price increases are visible across the country. In all provinces, house prices rose in the second half of last year. Nevertheless, there are considerable differences between regions' average purchase prices.

Share of first-time buyers in transactions increased

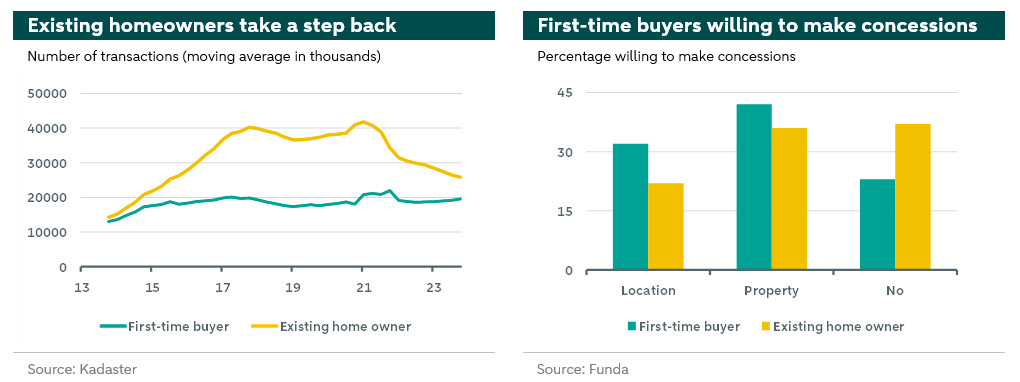

The number of transactions is also cautiously picking up, mainly because more flats are being bought again. In January and February, transactions were even 13% higher than in the same two months last year. But all in all, the number of transactions is still particularly low. Last year, a total of only 182,000 existing owner-occupied houses changed hands. That is significantly lower than the average number of transactions in the previous five years of 218,000. For newly built houses, the drop is even sharper, less than 17,000 compared to close to 29,000 in the previous five years.

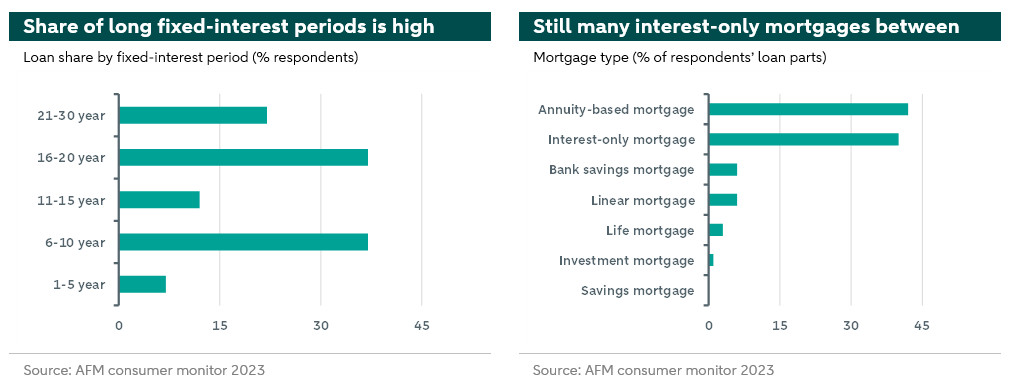

The low number of transactions is because are buying fewer homes, even though they have the option of taking the interest-free part of the mortgage and the old mortgage interest with them when they move. Only if they need to borrow an extra amount to buy the new home, or if they have fixed the fixed-interest period on the old mortgage for less than 10 years, those moving on can face the higher mortgage rates. However, only a minority of homeowners will be affected, as the majority have fixed mortgage rates for long to very long periods.

An important explanation for the reduced interest in moving house among home owners is that it is difficult to find a suitable home. There are few existing homes for sale. The supply of new-build homes also remains limited, although it has increased as buyers were less likely to move on, as new-build homes were relatively expensive relative to existing homes. In the absence of through-flow, the housing shortage is growing in both quantity and quality: there are too few houses and not everyone lives in a suitable home. According to NVM, there were only 23,284 existing and 13,920 new homes for sale on offer in the second quarter. The limited supply reinforces the preference to buy first and only then put one's home on sale, further adding to the shortfall of few homes for sale.

However, the number of transactions by first-time buyers remains stable. It is mainly first-time buyers with relatively high incomes and often relatively high rents in the liberalised segment who proceed to purchase homes. First-time buyers are relatively less sensitive to economic fluctuations in their purchase decision. An important explanation for this is that first-time buyers find it more difficult to postpone house purchases. They are more likely to have an urgent need to move because they have to move out of their house, want to move in together, have children or have to move because of a new job. When looking for a suitable house, first-time buyers are therefore willing to make more than existing homeowners.

What helps first-time buyers is that the limit for their has been raised this year. Buyers aged between 18 and 35 will not have to pay transfer tax when buying a home up to EUR 510,000. Last year, the limit was still at EUR 440,000. Furthermore, when determining the maximum mortgage amount, the current rather than the original education debt will be taken into account, and single people earning more than EUR 28,000 per year will be allowed to borrow more from 1 January. On the other hand, the donation tax exemption, which was previously reduced in stages, has now been abolished.

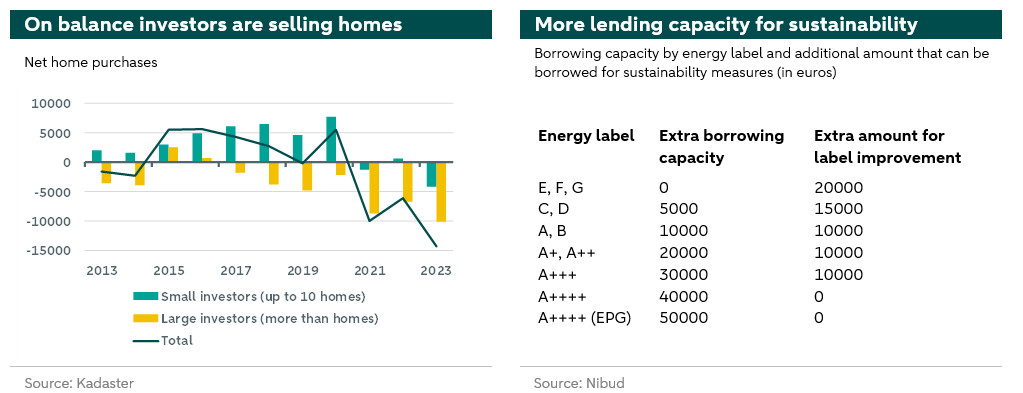

Investors less active

First-time buyers also have less to fear from investors buying up homes to rent out. Earlier, when interest rates were low, investors still regularly bought houses that were also in demand by first-time buyers. After all, when interest rates were low, the present value of future rental income was high. So high that first-time buyers who are limited by lending standards were outbidden. However, now that interest rates have risen, home rentals are becoming less attractive and other are coming back into the picture. Furthermore, interest in home rentals is dampened by measures taken by the government, which is raising taxes on landlords, imposing rent restrictions and allowing municipalities to ban home buying by investors through buyout protection.

Reflecting the decreased net return on rental properties, sold more homes last year than they bought. And if they buy homes, it is more often in a higher price category than before. However, it is not the case that investors are abandoning their rental properties en masse. In fact, their share in the total housing stock grew through new construction, housing split and transformation of offices and shops. But if the government manages to push the envisaged additional rent restriction measures through parliament, more investors will decide to sell their rental properties, especially cheap rental properties in municipalities with an average high price level. Divestment is often a slow process, as landlords prefer to sell the property when the tenant has left, as yields are higher then.

When investors sell rental properties, rental properties shift to the owner-occupied segment. This offers opportunities for first-time buyers, although they will have to be alert to the quality of the property on offer. Handymen are at an advantage. This is because investors will first give up on houses with a mediocre energy label, for instance, because the new housing valuation system takes more account of the quality of the rental property. The energy label, outdoor space and amenities in and around the house are valued with extra rental points, so that better-quality houses yield more rent than lower-quality houses.

Since the sharp rise in energy prices, buyers have become more alert to the energy label when buying a house. Many buyers houses with energy labels A, B and C and houses built after 2011 when searching for houses on the internet. Moreover, the change is reflected in prices and transactions. Houses with a good are valued more favourably than those with a weak energy label and are also selling faster. Now that energy prices have come down a bit and the stock of houses for sale is so limited, many buyers are once again paying more attention to houses with a moderate energy label.

What may play a role in the renewed interest in homes with a moderate energy label is the extra credit space included in the new income credit standards for buyers who want to make their homes more sustainable. This contributes to an increasing number of mortgage applications including an amount for energy-saving measures, although most homeowners still prefer to finance sustainability measures with their own savings. This does not alter the fact that the change is progress, especially since, from a practical and cost point of view, moving house is a natural time to improve energy efficiency. After all, the adjustments needed to reduce energy consumption can be done at the same time as other repairs.

The rebound in the total number of transactions early this year is partly due to the increase in the NHG purchase price limit from EUR 405,000 to EUR 435,000 in January. With energy-saving measures, the limit is even higher, EUR 461,100. This makes more buyers eligible for this guarantee scheme, which provides buyers with an interest rate advantage, enabling them to borrow a larger amount than would be possible without NHG. The adjustment of the NHG purchase limit contributes to a larger share of NHG in mortgage lending. As the average purchase price gets closer to the NHG purchase limit, the incentive to purchase a house is likely to decrease.

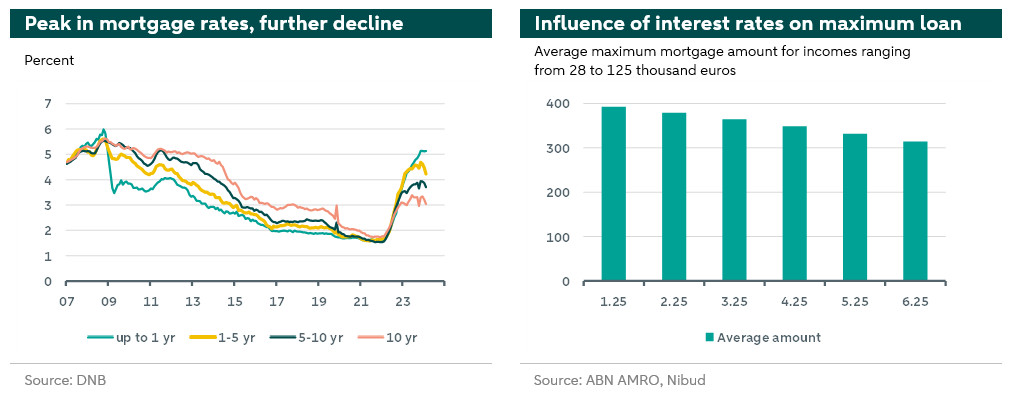

Turnaround in monetary policy heralds fall in mortgage rates

An even bigger stimulus for home buying is the reversal of mortgage rates. As it became clear that inflation in the eurozone is softening again towards the 2% target level, confidence grew that the European Central Bank (ECB) could cut its official interest rates. We expect the ECB to cut deposit rates, currently at 4%, in steps from June to 2.75% by the end of this year and 1.5% by the end of next year. In line with these cuts, interest rates on short-term fixed-rate mortgages will come down.

Interest rates on long-term fixed-rate mortgages have already fallen significantly in anticipation of the ECB rate cuts. Those 10-year rates on Dutch government bonds have fallen 70 basis points since October to 2.6% in April. We think 10-year yields will fall further, once there is more certainty about the ECB's stance. In our forecasts, we assume a 10-year rate of 2.2% by the end of this year. The 10-year mortgage rate, which tracks the 10-year rate on Dutch government bonds, will record a similar decline, in our view.

With lower mortgage interest rates, buyers are allowed to take out more mortgage according to the Nibud lending standards. How much more, depends on individual circumstances. Across the income spectrum, the mortgage amount to be borrowed is on average 2.25% higher when the mortgage interest rate drops from 3.75% to 3.25%. Thus, the expected fall in mortgage rates leads to additional credit space for homebuyers. Against this background, it makes sense for bank risk managers to take into account a loosening of credit conditions and an increase in demand for mortgage credit.

The fall in mortgage rates not only contributes to wider lending but also to improved affordability of homes. Affordability, measured by the ratio of net housing costs to net income, has deteriorated in recent years due to increased mortgage rates and higher house prices. Now that mortgage rates are falling and is rising faster due to the tight labour market, some improvement is shining again. But then house prices should not rise too fast, something that remains to be seen given the limited stock for sale and the re-emerging gap between bid and asking prices.

Nor is there any prospect of moderation in price development from the housing sector. Housing construction in the Netherlands traditionally hardly reacts to house price increases and now again lags far behind housing demand. All in all, houses were completed last year, while estimates suggest 115,000 are needed annually. Given the downward trend in the number of permits issued, the situation does not promise to improve any time soon.

Housing construction plagued by various problems

Housing construction is plagued by a series of problems. Project costs are rising due to higher interest rates. This while the negative between interest rate hikes by the central bank and construction activity in the Netherlands is relatively high. Furthermore, there is a lack of affordable building plots, building materials are expensive due to energy prices and labour costs are high due to the shortage of staff. In addition, municipalities face a shortage of staff capacity and construction projects are delayed due to objection procedures. These challenges make it difficult to get new construction projects off the ground, even if subsidies are provided for them. In 12 of the 27 projects selected for the first round of the Housing Impulse, the construction start was unfortunately not met.

Some improvement in housing construction is possible if the new , yet to be passed by the Lower House, is successful. According to this act, more direction will be given to the state on how many houses are built, where they should be located, and for whom they are built. The law pushes for more affordable housing, its proper regional distribution, and a shortening of objection procedures. The future should show whether this is also feasible with the high plot prices in some regions, the increasing workload at the Council of State, which in future will be the single point of contact for objection procedures, and the importance of potentially conflicting policy goals such as climate and nature with housing. Think of PFAS, for example. Finally, it is also interesting how the Housing Act relates to the Environment Act, which is precisely made for less direction from the state.

Another hopeful factor is industrialisation of the construction sector. Thanks to technological advances, there are increasing opportunities to build parts of houses in factories and assemble them on site. This saves costs, as it requires fewer staff, reduces material wastage and makes logistics in housing construction more manageable, allowing new homes to be realised faster. Nevertheless, there are still hurdles to overcome before industrial construction is scaled up to the point where the promise of quality at an affordable price can actually be realised.

Adjustments that promote cohabitation

The continuing housing shortage calls for more efficient use of the housing stock. This can be done by countering barriers to cohabitation. One obstacle is that the AOW and Social Security benefits are not individualised but depend on household composition. As a result, the joint benefit for those living together is lower than for those living seperately. However, individualisation of benefits can lead to higher public spending. So there is a trade-off between public finances and housing. There is also a trade-off between tenant protection and housing. Landlords and mortgage lenders are reluctant to allow subtenancy because the subtenant accrues rights and is allowed to stay in the property when the main tenant changes, or if the homeowner wants to sell the property. The next government will have to assess whether the current choices in these exchanges are still appropritate.

Repeated call for tax reform

Lagging new construction and low interest rates are not yet a guarantee that prices can go one way: up. In recent months, there have been renewed calls to cut tax incentives for owner-occupied housing. The judges that while the housing market has become less pro-cyclical thanks to the annuity repayment requirement and tightened lending standards, tax incentives still need to be further phased out to enhance housing market stability.

The call to cut schemes like the mortgage interest deduction is in line with the conclusions of the , which is critical of its effectiveness (does it actually lead to more home ownership?), efficiency (does it achieve the goal at low social cost?) and practicability (can the tax administration handle it) in the longer term. However, among the political parties currently in formation, there is little political support for adjustment. Delaying reforms does raise the risk of having to make abrupt changes in the future, increasing the risk of house price shocks.

Climate change may also lead to price shocks

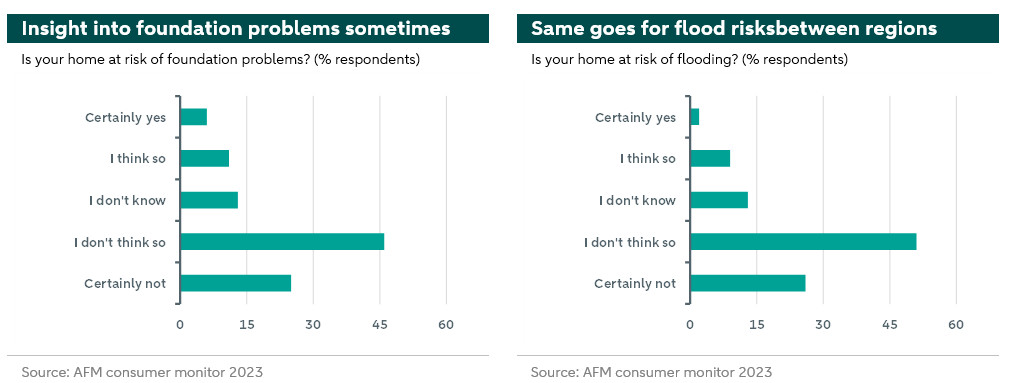

The risk of house price shocks if reforms are delayed also plays out with climate change. For example, homeowners are poorly informed about and what preventive measures they can take to limit damages. More information is also needed regarding foundation risk, according to the . In addition, the Council recommends preventive interventions, such as raising the water level, and ensuring subsidies and credits for repairing foundation damage. The Council estimates that the total amount of damage without preventive measures could reach EUR 54 bln, a hefty sum compared to the value of the total housing stock of EUR 2,100 bln in 2022.

In the context of climate change, economists from the argue for a sustainability requirement for home purchases. In addition, they suggest introducing a uniform climate label. Such a climate label makes buyers aware of climate change-related financial risks and can help ensure that potential climate damages are better factored into the house value. However, introducing such a climate label requires more and better climate data at the level of individual homes, which is not an easy task. An alternative could be to include climate risks in the valuation.

Making the housing stock more sustainable requires additional investments, which will be financed partly from own resources and partly from mortgages. The total outstanding at the end of last year was EUR 826bn, and including family mortgages, an estimated EUR 900bn. Relative to GDP, mortgage debt is high in an international perspective. Multilateral organisations such as the IMF and OECD therefore regularly advise the Dutch government to reduce mortgage debt, although they acknowledge that Dutch households have solid financial buffers with their high pension savings.

Moreover, judging by , credit risks in the Netherlands remain manageable. At the end of October, only 27,000 were in arrears on their mortgages of three months or more. The fact that so few mortgage lenders got into trouble, despite the energy crisis and higher mortgage interest rates, has to do with the robust labour market and the long fixed-interest periods that mortgage loans are fixed at. A survey commissioned by showed that 1 in 10 mortgage lenders have to decide on a new fixed-interest period within three years and 9 in 10 fixed-interest mortgage lenders do not expect to run into problems when the fixed-interest period expires.