Global Outlook 2022 - Five key questions for 2022

Uncertainty over the economic outlook is now arguably the highest it has been since the start of the pandemic in early 2020. While economic growth has been strong, as economies have largely opened up, the supply-side has struggled to keep up with resurgent demand, with the consequence being inflation.

Following a rapid, post-lockdown recovery in 2021, uncertainty has come back to cloud the outlook

Unexpectedly persistent inflation, the resurgent pandemic, and a new threat to the recovery in the form of Omicron pose downside risks to growth, and raise the prospect of earlier interest rate rises

Still, we expect growth to remain above trend in 2022, and inflation to ultimately moderate

Upside risks to the US inflation outlook have led us to bring forward the timing of Fed rate hikes

We do not expect the ECB to follow, but rising US rates will still push European bond yields higher

In this Global Outlook, we explore five key questions informing our calls and assumptions for 2022

We also devote special chapters to Omicron and alternative pandemic and rates scenarios

Regional Outlooks: We expect a resumption in above-trend growth in the eurozone and the Netherlands following a soft patch, with inflation falling back below the ECB target by end-2022

In contrast, in the US excess goods demand and a tight labour market will keep inflation above target

The Brexit-pandemic supply crunch could trigger rate hikes as soon as this month in the UK

China’s zero-tolerance covid-19 policy and real estate pose ongoing growth risks in Year of the Tiger

The looming Fed-ECB policy divergence will pull eurozone bond yields higher, and weigh on the euro

Uncertainty over the economic outlook is now arguably the highest it has been since the start of the pandemic in early 2020. While economic growth has been strong, as economies have largely opened up, the supply-side has struggled to keep up with resurgent demand, with the consequence being inflation. This has brought forward the likely timing of interest rate rises in the US, and while we do not expect the ECB to follow, given the very different macroeconomic circumstances in the eurozone, this will have global spill-over effects over the coming year. If that were not enough to contend with, many eurozone countries are now struggling to contain a new wave of pandemic infections, with potentially an entirely new challenge for policymakers looming in the form of the Omicron variant. We think it is too early to judge the precise impact of this new variant on our growth outlook, but our initial take is that the new inflationary environment means policymakers will struggle to provide the same kind of support for demand that we saw throughout much of the pandemic, and that there will be more focus on alleviating supply-side problems – which could well be exacerbated by the spread of Omicron. In grappling with these near-term challenges, we should not lose sight of the longer term big picture challenges of climate change and the energy transition. COP26 saw progress being made in terms of government pledges and targets. However, there remains a sizable gap between pledges and current policy, and we continue to think the window of opportunity to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees in an orderly manner is closing fast.

Given the varied drivers of the outlook over the coming year, in this Global Outlook we have asked our experts to give their views on a range of topics, in the form of five key questions and answers. We also devote special chapters to the Omicron variant, alternative pandemic and interest rate scenarios, and the impact of central bank policy on global financial markets. Finally, given that one of the dominant themes next year is likely to be divergence between key regions of the global economy, we invite readers to refer to our country and regional outlooks to get a more detailed view on a given economy.

Wherever economic developments take us, we wish our readers a restful holiday period, and a happy new year!

Outlook 2022: Continued above trend growth, but bottlenecks and Fed rate hikes are a dampener

In big picture terms, we expect the post-pandemic recovery to continue in 2022, with above trend growth in the eurozone, the US and China. However, growth will continue to be constrained by residual supply-side bottlenecks, and upside risks to US inflation will trigger Fed rate hikes, driving a global tightening of financial conditions. The spread of the new Omicron variant poses downside risks to growth, but upside risks to inflation.

In the below Q&A, we explore five questions informing our key judgment calls and assumptions for 2022.

1. When will supply bottlenecks resolve?

Pandemic-related disturbances have caused a wide range of supply-side bottlenecks over the past year, in areas such as raw materials, intermediate goods – including semiconductors – and freight transport (as well as in the labour market). Efforts by suppliers to build buffers, in reaction to the threat of scarcity of certain goods, has contributed to shortages, exposing the vulnerabilities of global ‘just in time’ supply networks. Meanwhile, supply-demand imbalances have been aggravated by a pandemic-related demand shift from services to goods, particularly in the US. These imbalances have not only formed a constraining factor in the global industrial rebound from the pandemic shock, but have also contributed to a pick-up in inflation. All of this is shown for instance by a decline in global manufacturing PMIs over the past months, certainly when corrected for record long delivery times (particularly in advanced economies). Other illustrations are the near-doubling of lead times for semiconductors (causing temporary production stops in high-tech industries, particularly in the car sector), a seven-fold rise in global container freight tariffs, and a sharp uptick in the global PMI subindices for input and output costs driven by a surge in commodity prices.

A common factor driving these bottlenecks is the direct effect from pandemic flare-ups on labour supply and on production facilities and supply chains. For instance, earlier this year delta outbreaks in China caused a temporary partial closure of the country’s second-largest port. Delta-related factory closures in Malaysia also added to a further lengthening of lead times for chips. Taken from this perspective, if one of the key assumptions for our outlook will prove correct – that 2022 will see less pandemic disturbances compared to 2021 – that should imply a fading of these supply bottlenecks in the course of next year. And if another key assumption – that reopenings will support a rotation in consumption from goods to services – will also hold, that would also help to reduce these supply-demand imbalances. Early indications of some easing of bottlenecks are visible in container freight tariffs (that have dropped by 10-20% over the past months), and in some easing in the monthly rise of lead times for semiconductors.

However, caution is warranted. First, we should be careful in generalising these supply issues. The dynamics behind for instance the rise in container freight tariffs, the scarcity in semiconductors and distortions in labour supply (which we cover in Question 2 and the regional outlooks) do have some commonalities, but also clear differences.

Second, some of these supply-side imbalances are driven by country specific factors, think of diverging demand conditions or different labour market circumstances. Third, the spread of Omicron and/or other new covid-19 variants may lengthen the process towards supply chain normalisation and hence make the supply bottlenecks even more persistent than they have already been so far. (Arjen van Dijkhuizen)

2. Why is the outlook for inflation – and therefore interest rates – so different in the US and eurozone?

Inflation has surged in both the US and in the eurozone over the past year, with US CPI inflation reaching a 30 year high of 6.2% y/y in October, and eurozone inflation hitting a record 4.9% in November, according to the flash estimate. Inflation in both regions has been boosted by surging energy costs, with a bigger contribution from petrol price rises in the US, and natural gas prices in the eurozone. Where inflation trends have differed significantly is in core prices. While core inflation has also risen in eurozone, at 2.6% in November it is nowhere near as elevated as the 4.6% reading from October in the US. Looking ahead, while core inflation is expected to fall back in both regions in 2022, in the US we expect core inflation to remain somewhat above the Fed’s 2% target, while in the eurozone we expect inflation to fall comfortably back below target.

We see three key reasons for the divergent inflation trends in the US and the eurozone. First, while both regions have been affected significantly by supply-side disruptions, in the US this has been compounded by excess demand for goods, spurred by significantly more generous stimulus that overcompensated lost incomes from the pandemic (i.e. many workers were receiving more via fiscal transfers than when they were in employment). In the eurozone in contrast, the wage subsidy schemes merely sought to maintain employment and income levels rather than to stimulate demand. The result is a starkly different outcome for consumption in the two regions, which is clearly evident when comparing retail sales: in the US, retail sales have been persistently well above the pre-pandemic trend since early 2021, while in the eurozone there has been no such excess demand – sales have been broadly in line with the pre-pandemic trend. This difference in demand has given producers and retailers in the US much greater confidence in passing on higher costs to consumers.

Second, the output gap is much bigger in the eurozone than in the US. The US economy has comfortably surpassed its pre-pandemic peak, and is on course to close the output gap from the pandemic entirely by Q2 next year; in the eurozone we do not expect this to happen until 2024. Nowhere is this difference more apparent than in labour markets. In the US, the labour market looks already to be near full employment, with a record quit rate and elevated wage growth, while in the eurozone – notwithstanding pockets of tightness in some northern economies – slack remains significant, and wage growth has actually slowed at the aggregate level, to 1.4% y/y in Q3, down from 1.8% in Q4 and 2.2% in 2019.

Third, aside from a greater degree of slack, one other reason for more subdued wage growth – and in turn inflation – in the eurozone is historically lower inflation expectations, driven by prolonged periods in which inflation has significantly undershot the ECB’s 2% target. While inflation is above target now, it will likely take a much more sustained rise in inflation to meaningfully lift future expectations, and this should further restrain wage growth in the near term.

As a result of these significant differences between the US and eurozone, we expect a major policy divergence to open up between Fed and ECB policy over the coming years, with the fed funds rate rising to 2.5-2.75% by 2025, while the ECB is not expected to raise interest rates over our forecast horizon (to end-2023). Even so, European bond markets do not exist in isolation, and we expect spillovers from rises in US interest rates to put upward pressure on eurozone bond yields as well next year. For more, see our special chapter on central banks and financial markets. (Bill Diviney, Aline Schuiling, Nick Kounis)

3. Will Fed rate hikes trigger a major tightening in financial conditions, and might this stay the Fed’s hand?

As the Fed begins to raise interest rates, financial markets tend to move pre-emptively to price in the tightening cycle – bond yields rise and this can trigger a deterioration in investor sentiment. Financial conditions are a key transmission channel for monetary policy – equity market moves have wealth effects and consumer confidence in the US is often heavily impacted by market moves, while mortgage rates tend to track long-term bond yields. As such, the Fed is mindful of the reactions in markets – globally as well as domestically – as these moves can do much of the tightening work for it. In other words, there is a risk of policy overshooting if the Fed continues to raise rates regardless of financial market developments. Indeed, in the past the Fed has shown flexibility in the face of a significant tightening in financial conditions, most notably in early 2016, just after the first rate hike of that cycle, when the S&P 500 rapidly corrected by around 13%, and also in early 2019, when equities declined by a much bigger 20% but over a longer period (see chart below, with reference to Fed policy statements from that time). On both occasions, the Fed paused rate rises (2016), or put an end to them entirely and even began reversing course (2019).

After bringing forward our expectation for the start of Fed rate hikes to June next year, from early 2023 previously, we also significantly raised our end-2022 forecast for the 10y Treasury yield, to 2.6% from 1.7% previously. Should our forecast for the Fed and bond yields pan out, this raises the risks of a deterioration in investor sentiment. Such a correction could well fit the parameters that in the past caused the Fed to pause in its policy tightening.

However, we think the bar would be significantly higher this time around for the Fed to pause or reverse course, primarily because of the radically different inflation environment. In both 2016 and 2019, inflationary pressure was subdued and had been undershooting the Fed’s target for some time; indeed, the Fed was hiking on the expectation that inflation would rise, rather than to bring down realised inflation. As such, although the Fed would still take into account a tightening of financial conditions, it would next time have to weigh this against likely continued upside risks to inflation. In that scenario, the Fed might well conclude that inflation is a bigger concern for the outlook than a major correction in equity markets. This suggests the hit to global growth could be larger than in previous Fed tightening cycles. (Bill Diviney, Shanawaz Bhimji)

4. Will EMs suffer from Fed tapering/lift-off and rising US rates?

A related question is to what extent a global tightening of financial conditions triggered by an earlier Fed lift-off will hurt a further post-pandemic rebound in emerging markets (EMs). History shows that Fed tapering and rising US policy and market rates are typically a negative factor for EMs. As ‘risk free’ rates rise and the dollar strengthens, investors will be less prone to a search for yield, reducing the relative appetite of the EM asset class. As the chart shows, previous periods of rising US rates typically coincided with periods of net portfolio outflows from EMs, putting pressure on EM currencies and other assets. We should add that the length and severity of such risk-off periods and their impact on net portfolio flows to EMs is impacted by many more factors than just US rates. What is more, following a surge in flows to EMs in late 2020 (partly driven by the outcome of the US presidential elections), portfolio flows to EMs have already started coming down sharply in the course of 2021, impacting relative valuations of EM assets.

Looking ahead, we expect tighter global financial conditions, rising US rates and US dollar strength to again trigger bouts of volatility and have a net negative impact on EM currency and asset markets and on EM growth. That will be particularly true for EMs with vulnerable fiscal and external metrics and high inflation. EMs will be faced with higher financing costs, while EM central banks – particularly those of the riskier ones – will likely be forced to raise domestic policy rates further to stem currency pressures and related inflationary pressures. As far as the most externally vulnerable EMs are concerned, all of this may even lead to a higher number of countries facing problems in servicing external debt obligations.

We have cut some of our EM growth forecasts on our updated Fed view. Still, for 2022, our global base case assumes continued above trend growth in developed economies, on the back of a normalisation in service sectors and industrial supply chains. This should be beneficial for EMs as well. Moreover, we still see some room for post-pandemic catch-up growth in many EMs, which generally have been lagging in terms of vaccination programmes. While overall EM GDP has surpassed pre-pandemic levels already, EM GDP per end-2021 will still be around 4.5 %-points below the level that was expected pre-pandemic. All in all, we expect EM growth to fall from around 6.5% in 2021 to around 4.5% in 2022. Obviously, a key downside risk stems from serious virus flare-ups of new variants like Omicron and resulting policy tightening (including the persistence of zero-tolerance COVID-19 policies in China and some other Asian countries), which would further delay a normalisation in services sectors and in industrial supply chains. (Arjen van Dijkhuizen)

5. How does COP26 impact the economic outlook?

COP26 saw progress made in terms of government pledges and targets. On this basis, the global temperature rise could be limited to 1.8 degrees. However pledges and targets are not policies, and on the basis of stated policies, warming is still projected to reach 2.7 degrees at the end of the century. Whether or not there is follow through on targets via policies and investment will be crucial in terms of likely outcomes. In thinking about the economic effects, it is therefore useful to assess the impact of both 1.8 and 2.7 degree scenarios. The first scenario – where policy action comes through but takes time – is one where transition risks predominate (the economic effects from policies implemented to reduce emissions), while the latter is one where physical risks (economic effects from actual climate change) come to the fore. Governments have committed to review and possibly enhance ambitions ahead of next year’s COP, so a Net Zero scenario that limits warming to 1.5 degrees is still possible, but the window of opportunity to achieve that is closing fast, and we do not regard it as the most likely scenario. An orderly Net Zero scenario – that leads to immediate and smooth policy action and fast technological progress – would limit the impact of both transition and physical risks compared to the two other scenarios.

The chart on the right above shows the projected economic impact of the three scenarios over the coming decades as estimated by the NGFS. In all scenarios, the economic effects materialise over many years and the impact on our regular 2-year business cycle forecasting horizon are modest. Negative transition shocks mainly emanate from higher carbon prices and energy costs, and heightened uncertainty in disorderly scenarios. The positive impulse comes from investment to facilitate the transition, and in the orderly Net Zero scenario carbon revenues are fully recycled to this aim as well as lowering employment taxes. The negative impact of climate change in the projections above is mainly factored in through lower productivity. Other transmission channels – such as from severe weather, sea level rise and migration – are not yet captured. So it is quite likely that physical risks, especially in the higher temperature scenarios, are underestimated. (Nick Kounis)

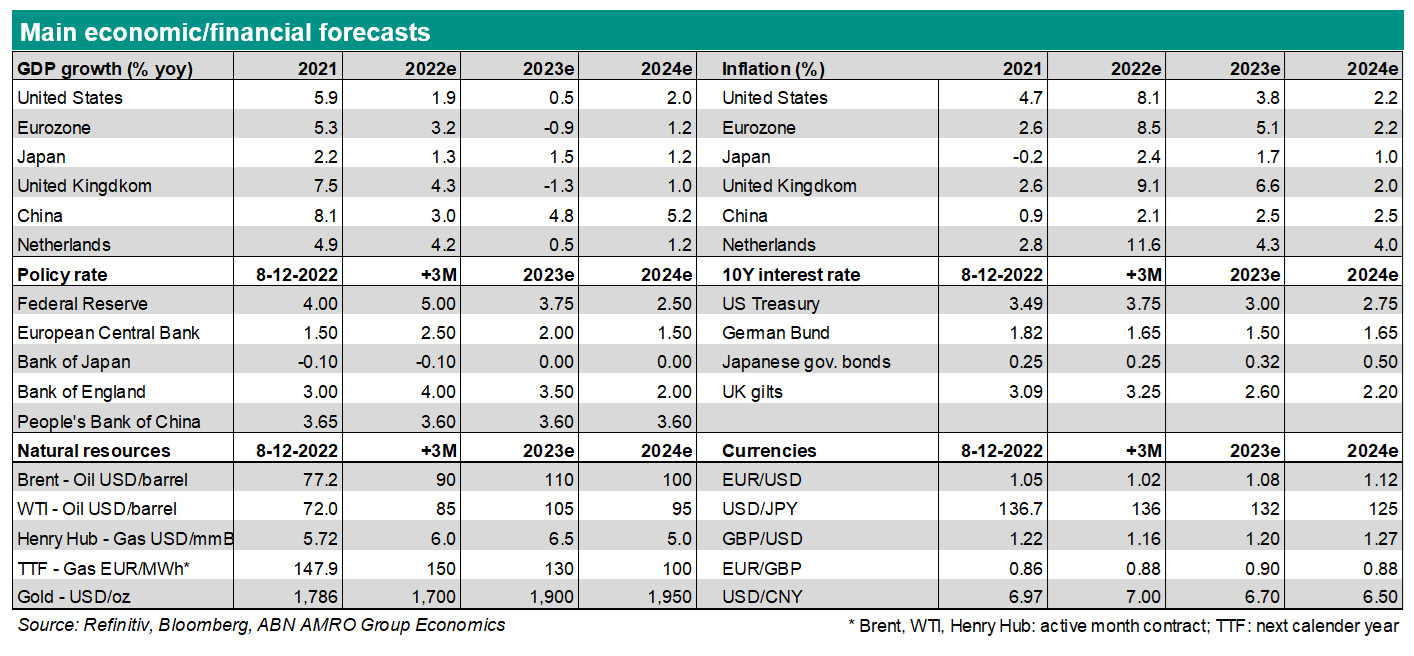

In the below table, we summarise our key judgment calls and assumptions for macro and financial market developments in 2022.