Global Monthly - Will wage growth fall back in time for summer rate cuts?

Continued economic resilience has driven a significant paring back in market expectations for Fed & ECB rate cuts. Market expectations are now consistent with our own call for a June start to rate cuts. But what if wage growth – the current obsession of central banks – proves more persistent? While central banks are likely to gain more confidence in the wage and inflation outlook by June, we think they will need to take a leap of faith in order to avoid the risk of being too late with rate cuts.

Global View: June rate cuts will require confidence – rather than certainty – on wages

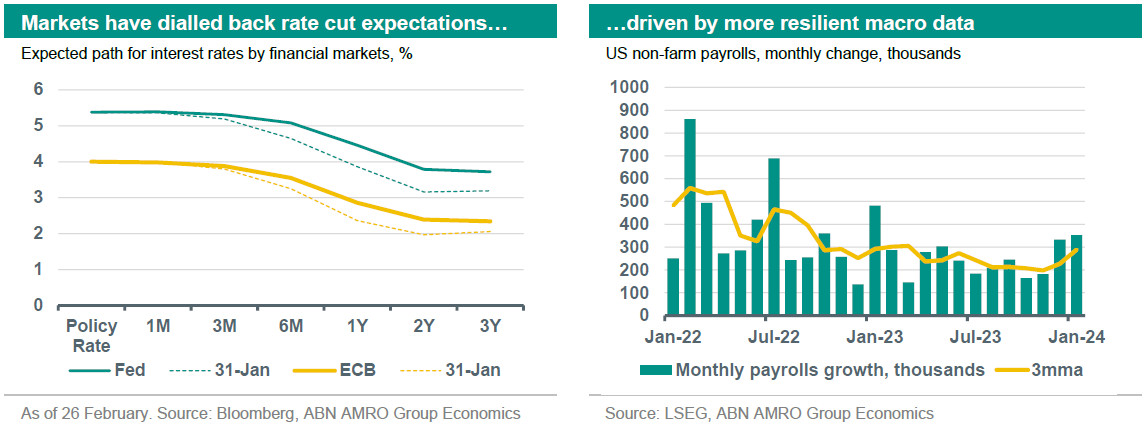

Bond markets now expect significantly less rate cuts by central banks than they did only a month ago. On the eve of the blockbuster US non-farm payrolls release early this month, markets were still out of kilter with our expectation for a June start to rate cuts, seeing a significant probability of a move in March. Now, markets are even beginning to cast doubt on June: at the time of publication, a June cut by the Fed is around 80% priced (for the ECB, a June cut is still fully priced – just about). This has driven a sharp rebound in bond yields, with the 10y German bund yield rising 25bp, and the 10y US Treasury yield rising 40bp over the past month. What has happened on the macro front to cause such a shift? First, the US employment report suggested an even more resilient economy than the already benign expectations of most forecasters. Second, while the eurozone remains weak, it has also continued to outperform expectations for even greater weakness. At the same time, while disinflation has broadly continued in advanced economies, a hot CPI and wage growth reading in the US reminded investors that we may not be quite out of the inflationary woods. For now, while markets have moved in our direction over the past month, we think the pricing out of rate cuts is likely to run out of steam. As we lay out in this month’s Global View, while advanced economies are proving resilient, we continue to think central banks will gain sufficient confidence in wage (and therefore inflation) developments to start lowering rates this coming June.

Growth is looking a little better than expected, but driven mostly by the US

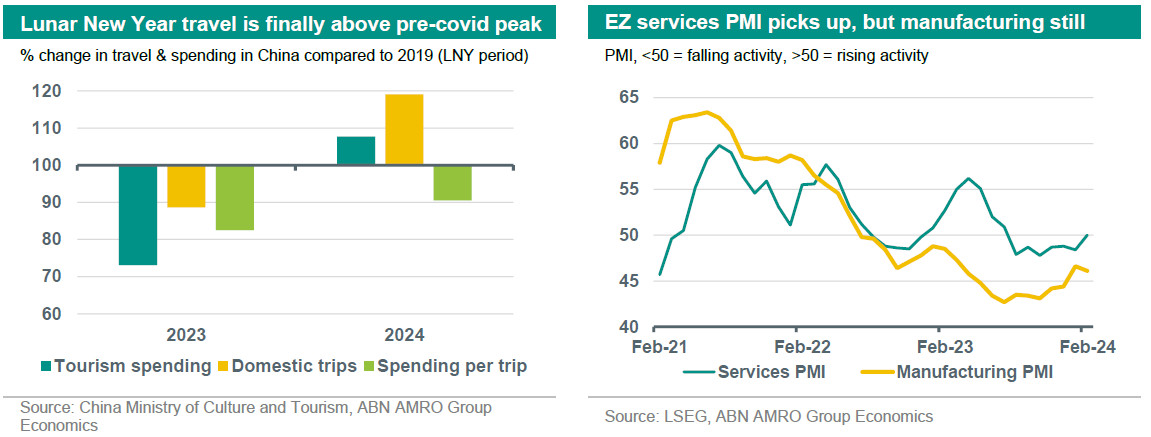

To some extent, the later start to rate cuts now expected by financial markets has been driven by commentary from Fed and ECB officials, who have sought to downplay expectations for an imminent move on rates. For the most part, however, the data has spoken for itself: growth indicators have largely come in on the stronger side, particularly in the US, but we are also seeing some green shoots in the more sluggish eurozone and China. In the US, the more resilient labour market suggests the unfolding slowdown is likely to be even shallower than we previously thought, leading us to raise our 2024 growth forecast from an already above-consensus 1.8% to 2.1%. We have made no such changes to our eurozone and China growth forecasts, but in these regions, too, there has been some cause for optimism. The eurozone economy has stagnated rather than contracted, with Q4 GDP posting a flat reading – above our expectation for a 0.2% q/q decline – meaning the region might just dodge a technical recession after all (provided there are no downward revisions). In China, the Lunar New Year holiday suggests consumers might be beginning to shake off the post-reopening gloom, with tourism spending and the number of trips taken during the holiday finally surpassing the pre-covid peak – with trips some 20% higher. While the data is likely flattered by the extra day of holiday this year, we still see it as a sign that growth in China has bottomed out.

Looking ahead, we still expect Q1 to be a relatively weak quarter. Growth in the US already slowed notably in Q4, albeit to rates that are still above trend, and the January activity data (particularly the fall in retail sales) suggests the economy is slowing further moving into 2024. In the eurozone, we expect growth to remain weighed by high rates and the rollback of fiscal support amid the easing energy crisis. Indeed, while the flash services PMI for February improved notably, likely helped by growth in real incomes as inflation abates, industry still seems to be in the doldrums, with the manufacturing PMI staying well below the neutral 50 mark. Beyond the near term, we expect a modest pickup in growth as we move into the second half of 2024, driven by falling interest rates in advanced economies, and as the cumulative impact of China’s piecemeal, targeted stimulus efforts bears fruit. The recovery is likely to be constrained by the still-restrictive level of interest rates. But as the green shoots in China and the eurozone suggest, a recovery is coming, even if it is likely to be shallow.

What if rate cuts don’t go according to plan?

As we describe above, the expected fall in interest rates is a key driver of our modest growth expectations for the second half of 2024. But what if the Fed and ECB are unable to start lowering rates from June, as we expect? What are the chances that inflation proves more persistent, causing rate cuts to be delayed to later in 2024 (or beyond)?

In our January Monthly, we focused on the risks to the inflation outlook from the Red Sea shipping disturbances. Since then, shipping freight tariffs have already begun to subside, and we continue to think the ultimate impact on inflation will be limited. If anything, we see evidence (1) that any upward pressure is still likely to be overwhelmed by the pass-through of prior falls in shipping and commodity prices. This leaves the main upside risk to the inflation outlook coming from wage growth. Throughout the previous high inflation period, the biggest fear of central banks was that the run-up in prices would trigger unsustainably large wage rises, which in turn would feed back into price growth, keeping inflation above 2%. As we argue below, we think central banks will have more convincing evidence that wages are normalising come June, but that they will still likely need to take a leap of faith in order to balance the risk of cutting rates too early (which could lead to inflation persisting) against cutting rates too late (which could keep the economy unnecessarily weak – or worse, cause a recession).

Wage growth needs to fall to between 3.3-4% in the US, and 2.7-3% in the eurozone

Before we look at future developments, we need to first define the level of wage growth central bank need to see to be confident inflation falls back to – and stays at – 2%. Broadly, wage growth needs to be at a level equivalent to the inflation target of 2%, plus long-run productivity growth.

Productivity growth is notoriously volatile and difficult to predict, and so central banks typically look at long term trends to inform their assumptions. Short-run (2014-19) productivity growth just prior to the pandemic was relatively weak: 1.3% in the US, and 0.7% in the eurozone. Over the longer run (2000-19) (2), productivity was much stronger, at 2.0% in the US and 1.0% in the eurozone. Adding these ranges to the 2% inflation target, we get a wage growth target of 3.3-4.0% in the US, and a narrower 2.7-3.0% range in the eurozone. Notably, these ranges are higher than average wage growth levels just before the pandemic. Indeed before the pandemic, central banks faced the opposite problem of too low inflation (HICP inflation averaged just 1.2% in the eurozone, and PCE inflation 1.6%). This analysis suggests that central banks will not want to see wage growth falling back to pre-pandemic levels, but rather to levels that are a little above those before the pandemic.

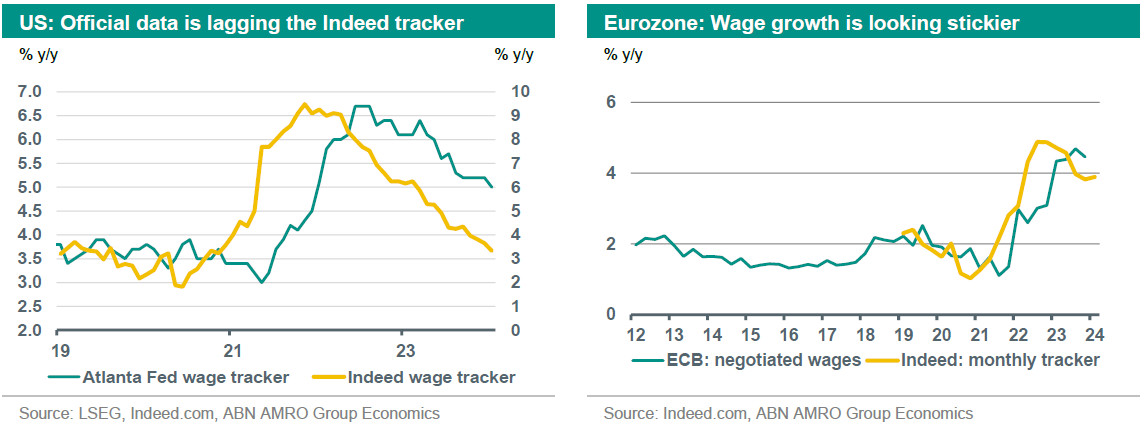

Wage growth is tantalisingly close to target levels in the US; still a way to go in the eurozone

On most official measures, our estimates above suggest that wage growth still has a significant way to fall in both the US and the eurozone. The Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker is – at 5% as of January – still 1-1.5pp higher than it ideally should be. However, although this measure is probably the most accurate read on wage growth in the US, it is also very lagging. The Indeed wage tracker – which uses posted salary data for new vacancies – has proven to be a strong leading indicator since its launch in 2019, suggests that wage growth is already almost back near 2019 levels. Based on the previous relationship between the two indicators, we think the Atlanta Fed’s tracker will likely hit a level consistent with 2% inflation most likely in the second half of this year. In the eurozone, official measures of wage growth and the Indeed tracker are still well above 2019 levels, and well above even the most generous estimates of where wage needs to be for inflation to stay at 2%. The ECB’s negotiated wages measure is, at 4.5% as of Q4, around 1.5-2pp higher than it needs to be. But even the more timely Indeed tracker is around 1.8pp above 2019 levels, or around 1pp above the level that would be consistent with 2% inflation.

Eurozone: Saved by the weak economy?

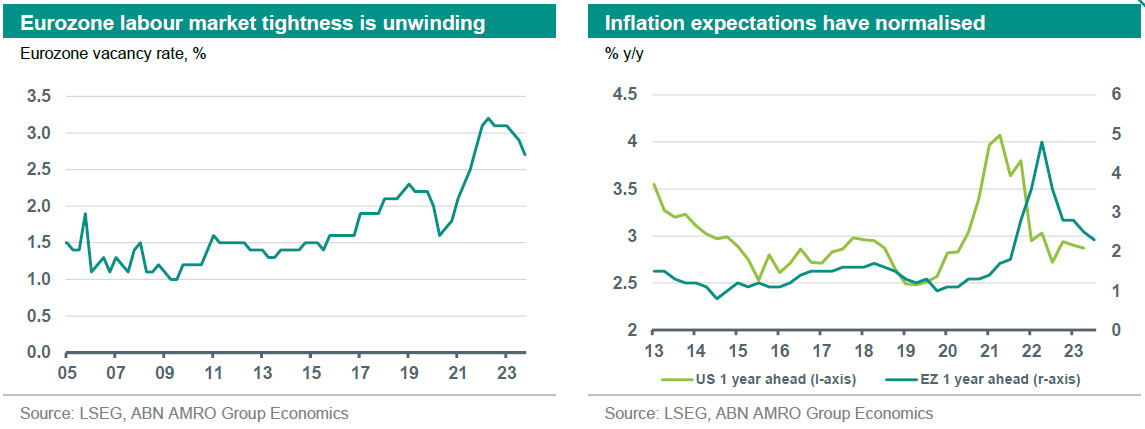

While the eurozone is facing a bigger overshoot in wage growth than in the US, the weaker macro-economic environment in Europe is driving a significant shift in the bargaining power of workers, which is likely to put more meaningful downward pressure on wages over time. Indeed, while the unemployment rate has been stable at historically low levels over the past year, the job vacancy rate has fallen sharply, from a peak of 3.2% in Q2 22 to 2.7% as of Q4 23 – 0.5pp above the pre-pandemic peak of 2.2%. In other words, around half of the increase in labour market tightness since the pandemic has already unwound. With the economy expected to stay weak in the near-term, this softening in labour demand is likely to progress further over the coming months, pushing unemployment modestly higher. This easing in labour market tightness should help drive a further decline in wage growth by June, with that likely to be most readily evident in the Indeed tracker.

The other factor supporting declining wage growth is inflation expectations. As described in our January Monthly, much of the jump in wage growth has been driven by workers attempting to make up for lost purchasing power due to the energy crisis, and we now see evidence that inflation is being less frequently cited in collective wage bargaining negotiations. This is corroborated by measures of inflation expectations, which have largely normalised. If workers do not expect a repeat of the inflation surge of the past two years, the case for wage demands to persist at the current elevated rates is weakened.

What about those workers who have yet to be fully compensated for the inflation spike? Our analysis suggests that, in aggregate, eurozone wages have still not fully made up the shortfall created by the energy crisis (3). However, profit margins in the eurozone are also elevated. This means that businesses likely have the space to accommodate some further increase in wages – at least for a time – above what would be sustainable in the long-run (4).

Ultimately, the ECB will have to take a gamble when it does decide to cut rates. By the June Governing Council meeting, we think there will have been enough of a cooling in the leading indicators for wage growth to give the Governing Council the confidence that wage growth is on its way back to levels consistent with 2% inflation. Monetary policy works with ‘long and variable lags’, and to wait until wage growth has fully fallen back runs the risk of rates staying high for too long, and risking recession.

US: Even the Fed will have to take a gamble, albeit of a different sort

On the surface, wage dynamics in the US already look much more benign than in the eurozone, suggesting the Fed will be making less of a gamble by cutting rates in June. However, the Fed faces a different risk to the ECB, reflecting the different growth environment. So far, US outperformance has been accommodated by an improved supply side. As in the eurozone, although unemployment has held at historically low levels, measures of tightness – such as the job vacancy to unemployed ratio – have eased significantly. But with the economy defying expectations for a sharper slowdown, and evidence that the jobs slowdown is bottoming out, there is a non-negligible (perhaps 20%) chance the US sees a resurgence in wage pressures. The solid anchoring of inflation expectations, and the broad normalisation in the labour market means we would not have this scenario as our base case. But it does suggest that the Fed will also have to place its own bets come June.

We will soon publish a comprehensive Macro Watch on wage developments.

(2) We use averages from two time periods: 1) 2014-19: a relatively short period that avoids large cyclical distortions such as the eurozone debt crisis or global financial crisis; 2) 2000-19: a longer period that, alongside cyclical downturns, includes investment-fuelled bursts in productivity growth such as in the early 2000s (and which could be indicative of what an AI-fuelled upturn in productivity could look like

(3) Note that this does not include the effects of government support measures, which to some extent compensated households for their loss of real income. These measures were largely one-off and so did not permanently raise incomes.