Global Monthly - Will the energy squeeze threaten the recovery?

Soaring energy prices add fuel to fast-growing shortages that have already been inflationary. Consumers face both direct costs from heating bills, and price hikes as producers try to pass on their cost increases. However, government support is cushioning the blow. For producers, the risk of production outages is high in energy intensive sectors and in energy firms. Small firms are particularly vulnerable. In an economy already facing shortages, these production stops can have large knock-on effects.

We expect inflation to continue rising over the coming months. For 2022, we foresee bottlenecks slowly easing, and disinflationary forces re-emerging in the medium term

Regional updates (only in the pdf): we dive below the surface of recent inflation developments in the eurozone, while in the Netherlands, consumption and production faces new headwinds from the gas price rise

In the US, the delayed normalisation in consumption patterns means continued upside inflation risks

Growth slowed significantly in China in Q3, but policy easing should support a pickup in Q4

Global View: Will the energy squeeze threaten the recovery?

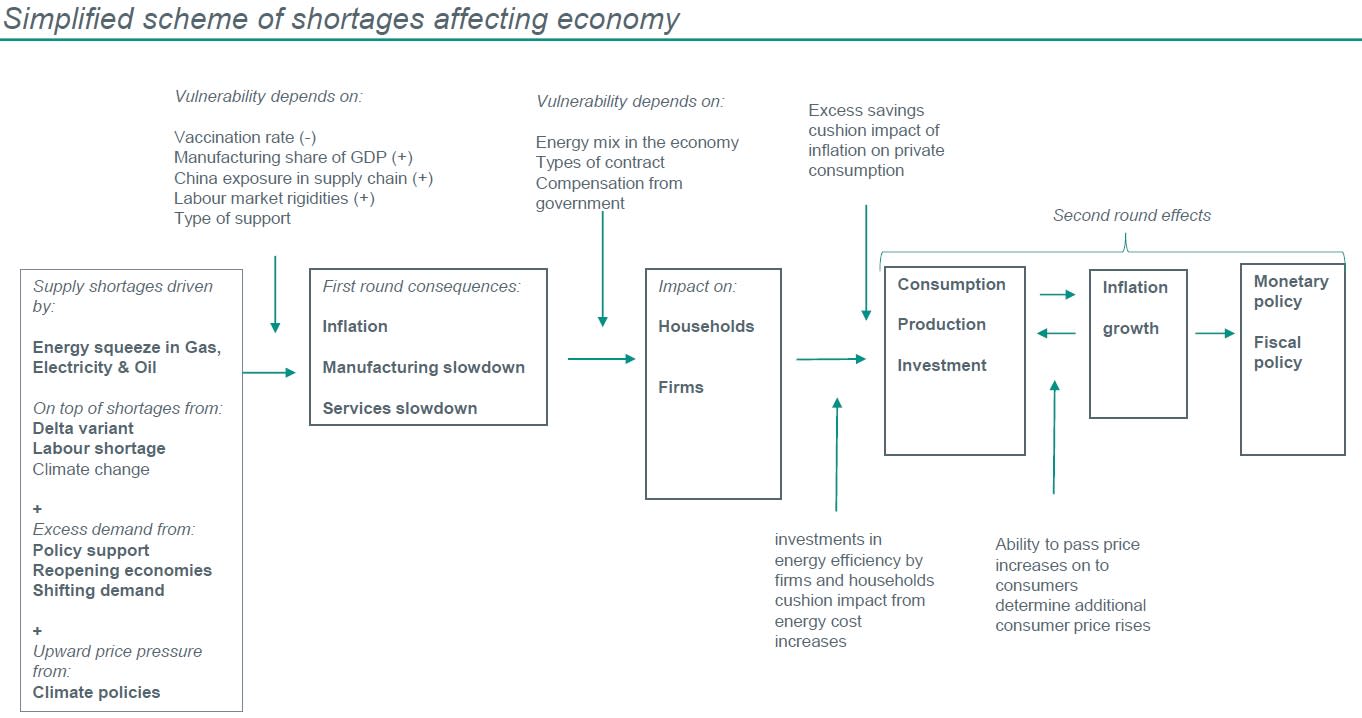

Supply chain bottlenecks have intensified further over the past month. Soaring energy prices are leaving consumers worried about upcoming energy bills as winter nears, while for firms, energy prices are yet another cost increase on top of already massive supply disruptions. Could this render business models unprofitable and cause widespread production outages? Or, if firms pass on price hikes to consumers, could it throw the post-pandemic recovery off track? In this month’s Global View we assess the extent to which energy price increases will spread through the economy and affect consumption and production going forward. We also look at the cushioning effect of both excess savings and government support on people’s ability to deal with these price rises. Our take is that while in the short run a demand fallback is likely to be limited, the risks are largely with the supply side of the economy, with more inflation ahead in the coming months which could amplify demand fallbacks over the course of 2022. While this poses downside risks to our economic outlook, we continue to expect above trend growth in the eurozone and the US over the coming quarters.

Where are energy prices going?

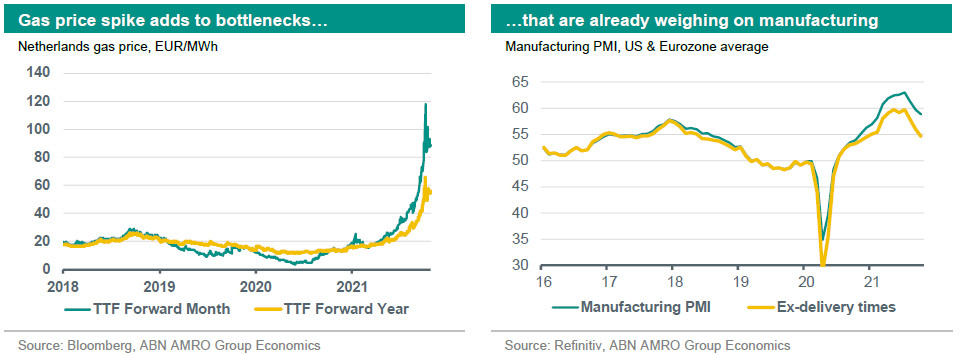

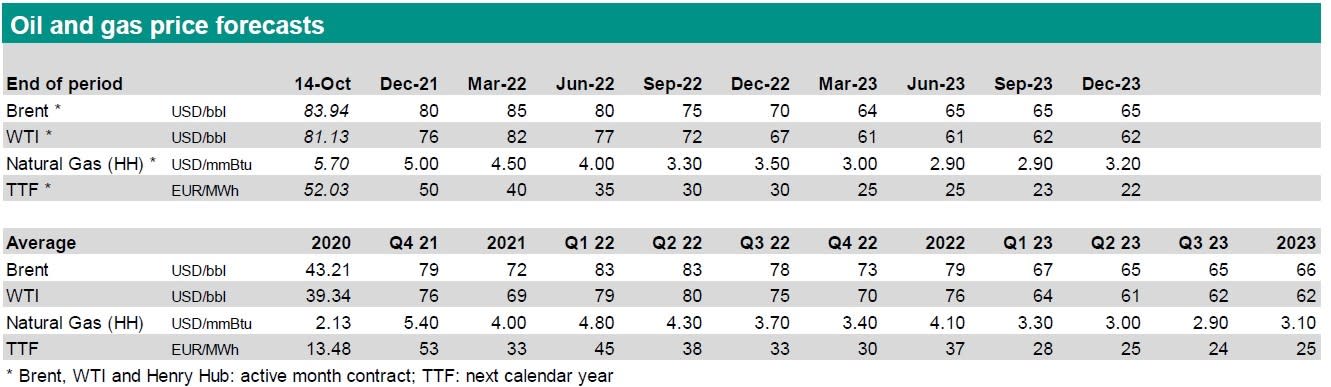

In big picture terms, we expect upward pressure on energy prices to persist through the winter months, but for prices to fall back by the end of next year – albeit to levels significantly higher than a year ago. For natural gas, the recent spike in prices was mostly in near-term contracts, with the month ahead contract in the Netherlands (TTF) briefly touching EUR 160/MWh, with it currently trading nearer to EUR 90/MWh. The price spike has come on the back of exceptionally low inventories heading into winter, and worries about whether supply would be sufficient in the event of a cold winter. Longer term contracts (one year ahead) are trading at much lower levels, suggesting the market is more relaxed about supply-demand dynamics in the medium term, though at EUR 55/MWh, prices are still around 4x where they were this time last year. Once the winter is behind us, we expect year-ahead prices to ease, falling back to EUR 30/MWh by end-2022 – still double where they were this time last year, and 50% higher than our previous forecast.

We expect a similar pattern in oil and electricity prices over the coming year. Oil demand is likely to continue increasing, although we expect supply to pick up as well via increased OPEC+ production. This should help dampen prices in the course of 2022, but our forecast of USD $70/barrel (Brent) at end-2022 is still almost double the level of this time last year. For electricity, prices are also elevated, due to shortfalls in renewables output and elevated prices of coal, gas, and carbon emissions permits (the EU ETS currently trades at around EUR 60/ton). Electricity prices at present are moving largely in line with gas prices, and there is a similar large difference between near-term contract price and the year ahead price. In tandem with gas, we expect electricity prices to ease once the winter is behind us, but to remain somewhat elevated given the high carbon price. See our latest Energy Outlook for more.

Energy crunch comes on top of massive supply issues

Alongside high energy prices, persistent supply bottlenecks are affecting a fast-increasing number of commodities and manufactured goods, while adding to inflationary pressures. The services sector is also being hampered, mainly by labour supply bottlenecks. While pandemic-related bottlenecks will ultimately ease as vaccination rates rise, economies fully reopen, and policy support is wound down, some bottlenecks are unlikely to ease soon. Disruption from climate change-driven extreme weather events, energy transition policies and shifting patterns of demand (linked to eg. home working) are likely to stay and in some cases intensify.

Weakened manufacturing growth from worsening shortages

Bottlenecks are putting an increasing constraint on global manufacturing. The global manufacturing PMI stabilised at a still relatively high level of 54.1 in September, around two points below the cyclical peak of 56.0 reached last May. This suggests further growth in global manufacturing is still on the cards, but momentum has fallen. The weakening momentum over the past months was initially driven by EMs (particularly China), but the aggregate index for DMs has also fallen with almost 3 points in the past few months, although remaining at a relatively high level (September: 57.1).

One shortage that has had a particularly widespread impact on manufacturing is in chips. The textbox below explains how numerous factors are contributing to the current shortages.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chips shortage: Not just due to the pandemic

Lead times for semiconductors are reported to have risen to an average of 22 weeks in September, compared to an average of around 12 weeks in the pre-pandemic year of 2019. The semiconductor shortage has had a particularly marked effect on the car industry, with automakers across the globe implementing production stops.

For this sector, growth has not merely slowed, but we are seeing sharp contractions in output. That is particularly true for Germany, although production rebounded somewhat in September. Other high-tech sectors are also facing constraints from this. For instance, Apple just made public that it had to scale back its production of the new iPhone 13 by over 10% this year due to the lack of chips. The production technology of a silicon chip – called wafer fabrication – is currently at about 95 percent of global capacity, according to research by Resilinc, a commodity chain research company. A growing number of applications worldwide in combination with few global players able to produce chips created a vulnerable situation to begin with. On top of that, distortions such as the US-China trade war, Covid-19 infections and extreme weather events (such as a drought that led to long production stops in Taiwan, one of the largest production sites) lowered supply. At the same time, home working and the reopening of economies caused a massive boom in demand. Resulting shortages led to hoarding behavior and stockpiling which made matters worse. Electric vehicle production and car production in general are amongst the worst affected industries.

While reported lead times are still rising, there are also some indications that supply-demand conditions are becoming more balanced. For instance, the delivery times sub-index of the global electronic equipment PMI has bottomed out. Also, with vaccinations rates in Asia rising (although with quite some divergence) and mobility restrictions in countries crucial for semiconductor supply chains (e.g. Taiwan, Malaysia, Vietnam) being lifted again, pandemic-related supply disruptions will be much less likely in 2022 compared to 2020-21. Another cushioning factor – at least in the longer run – is that policymakers in the US, Europe and Asia have taken measures to support domestic production capacity. For China, reducing foreign dependence on critical inputs such as semiconductors is a crucial aspect of its ‘dual circulation’ strategy. It will take time however before supply is substantially ramped up.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Impact on growth

The shortages described above impact inflation and growth through various channels. The scheme below shows the main channels through which the current shortages work their way through the economy.

Energy squeeze is mainly a eurozone problem

The rise in energy costs adds to already overshooting inflation. While this overshoot is clearly higher in the US, the additional impact of energy price rises is within recent historical ranges. In the Eurozone however, the recent rise is unprecedented in modern times. The spike in energy prices will have a clear impact on energy-intensive producers and energy companies themselves. The lack of sufficient domestic energy sources and a high reliance on natural gas make the eurozone more vulnerable to the energy squeeze than the rest of the world.

Another risk for the Eurozone is that most of the inflation overshoot is driven by something that affects a broad swathe of households. It could have more pernicious effects on consumption than in the US, where the inflation overshoot is more narrow (mainly from cars).

Excess savings could save the day...

One cushioning effect on private consumption could come from excess savings. During the pandemic restrictions have induced involuntary savings which could now be softening the impact of excess inflation on consumption.

Cumulative excess savings are less in the eurozone, at 6% of GDP, compared to 10% of GDP in the US. Theoretically, this could provide a significant cushion to consumption, as the level of excess savings is clearly much greater than the excess inflation we are seeing (c.2-3pp above the ECB/Fed’s 2% inflation target). Excess savings are still accumulating, according to most recent data (Eurozone data runs to Q2; US data to August)

…if only they were available to those who need it most

Unfortunately, however, excess savings have less of a cushioning potential than would appear. While lower income households typically spend a larger proportion of their income on energy bills, excess savings have mostly accumulated in higher income groups.

For the Netherlands the figure below plots the energy quote (proportion of income spend on energy) and for the eurozone the excess savings by income group.

While not quite as heavily skewed in the eurozone as in the US, where 70 percent of increase in net worth since the pandemic started accrued to the top 20% highest earners, it appears that excess savings will do little to help the lowest income groups in the eurozone who are hit hardest by the rise in energy costs.

European households are being compensated

The European Commission presented a toolbox of measures on 13 October which member states can implement immediately without breaching EU rules. Alongside near-term measures such as compensation for households, the EC suggests medium-term measures such as stepping up investment in renewables and developing energy storage capacity. Furthermore, the EC will look into the benefits of joint acquisition of gas reserves, and will re-evaluate the benefits and drawbacks of the current internal energy market. In presenting this toolbox, the EC is clearly signaling that the near-term policy response to price rises is up to member states themselves. We have summarised the policy response of member states in the eurozone in the table below.

The measures announced clearly focus on the protection of households (i.e. the demand side) and to a much lesser extent on industry (the supply side). In Spain there are even plans to have renewable energy firms pay part of their additional profits to compensate higher consumer energy bills. In the Netherlands, too, budgetary rules state that unless determined otherwise, energy bill relief is to be financed within the current budgetary frame. This could lead to tax increases elsewhere for instance for firms. Overall, we judge that government support will significantly offset the hit from the gas price spike to household disposable incomes, although not fully. Indeed, this is one of the reasons for our below consensus growth forecast for the eurozone in 2022 (3.7% vs 4.3%).

Downside risks from production stops increase

Thus far, evidence of energy-intensive companies and energy suppliers having to (temporarily) halt operations, has remained anecdotal. In the UK, a dozen or so energy companies (with around 2 million customers) have gone into liquidation over the past few weeks due to the gas price spike. For the Netherlands, the energy-intensive greenhouse horticulture sector will be one of the hardest hit sectors. While hard to predict, these problems may last until well into next year (our energy economist does not expect a normalisation in gas prices to happen before 2023). The impact of the energy price spike depends naturally on the share of heavy industry in GDP value added. The Dutch economy relies heavily on services (over 75% of added value), and as such it is less vulnerable to large-supply side disruptions at a macro level. Nonetheless, we believe there are some instructive examples of the kind of disruptions we could expect more broadly, and this is something we look at in the following Box.

Which likely pushes inflation higher still...

With the risk of energy price rises adding more pressure to already stressed supply chains, disruptions are likely to push inflation higher still, at least in goods. This process likely still has some way to go, although we are unconvinced that services sector inflation will follow to anywhere near the same extent. Demand for services continues to lag that in goods, particularly in the US but also in Europe. While we expect a continued recovery in services consumption, we do not expect the same above-trend demand that we have seen for goods. As such, demand-side pressures for services should remain contained. This should ensure that major central banks do not overreact to recent rises in inflation (although the Bank of England looks set to be an outlier in this regard).

…while also hitting demand

Higher prices will ultimately trigger falls in demand as consumers become more reluctant to spend. In the US, the recent weakness in the Michigan consumer sentiment has been driven by consumer aversion to recent price hikes, particularly for cars. Thus, to some extent the problem is likely to provide its own solution, insofar that weaker demand eases pressure on supply chains. At the same time, production cuts and stoppages also have knock-on effects in reducing demand for labour as some firms will respond to supply chain challenges by reducing headcount or number of hours worked. This could therefore have knock-on effects on the labour market and on incomes, although this effect at present appears to be dwarfed by strong labour demand elsewhere in the economy.

The supply side will also recover… eventually

A combination of pandemic restrictions, shifting patterns of demand, and distortions from government support and energy policies have caused more longer-lasting disruption to the supply-side than expected (see scheme at the beginning of this article). But with vaccination rates approaching herd immunity levels in most advanced and major EM economies, and government support unwinding, these effects will eventually dissipate. For instance, in shipping, we already see some signs of easing, with freight tariffs from Shanghai to LA falling back 14% over the past month. In the labour market, we are still to see the effects on labour supply of the gradual withdrawal of wage subsidies in Europe, and of the expiry of benefit top-ups and schools reopening in the US. Reduced migration is something that has hampered labour supply in both the US and Europe, and so the recent easing in travel restrictions should help here. Responses to these policy changes is taking longer than expected, but they are still likely to happen. In the meantime, disruptions are putting a dampener on the recovery, raising downside risks to growth, even as upside risks to inflation have risen.