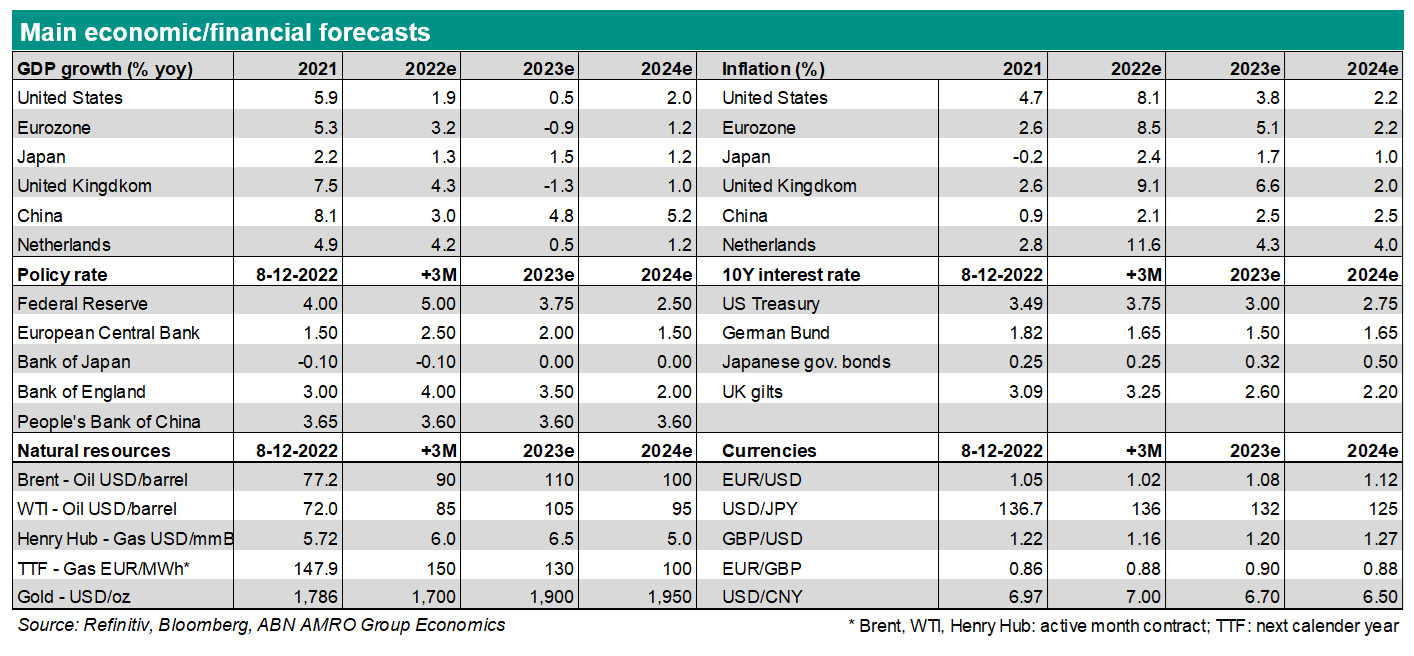

Global Monthly - Recession risk: How big is it?

The risk of recession is arguably now the highest it has been since the start of the pandemic in 2020. Inflation, the biggest fall in real incomes in decades, and central bank rate rises pose the biggest risk, with a potential Russian gas cut-off and China lockdowns adding to this. The massive accumulation of excess savings during the pandemic, and significant services recovery potential, are crucial offsets. But they may not be sufficient to prevent growth going into reverse.

For the regional updates on the eurozone, Netherlands, the US and China see the pdf below.

Global View: Recession risks are mounting

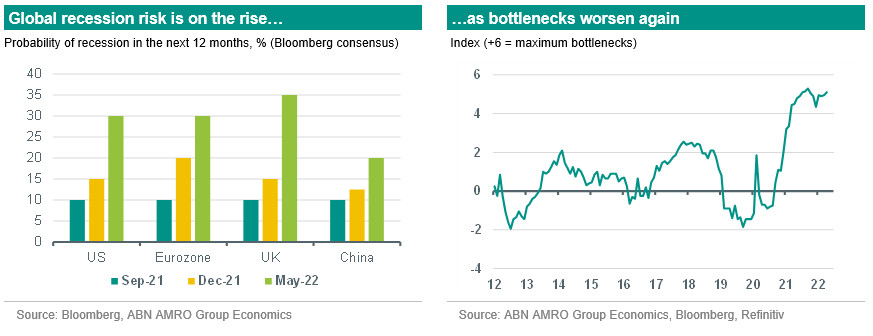

The cascade of shocks hitting the global economy has been relentless over the past half year. In advanced economies, the inflation shock is driving the biggest decline in real incomes for decades, while the monetary policy response of higher interest rates is adding to the squeeze on consumers and dampening business activity. Against this background, the war in Ukraine and unexpectedly prolonged and strict lockdowns in China have intensified the upside risks to inflation, and in turn interest rates. They also pose their own unique threats to global growth, with the ever-present risk of a cut-off in Russian gas supplies to Europe, and the risk of prolonged supply and demand shocks in China creating yet more turmoil for global supply chains. In the face of such threats, it would seem understandable for economists to forecast a global recession. We do not, at least not for now. Why is this? And how big is the risk of a recession over the coming year? The short answer is that there are crucial cushioning factors that should, with some luck, get the global economy through to the other side. These include the massive build-up of excess savings during the pandemic, strong labour markets, and a services sector that – for the most part – still has significant recovery potential. However, as we explain in this month’s Global View, even these offsets might not be enough to keep global growth on track, and we now judge the risk of a new recession to be the highest it has been since the start of the pandemic.

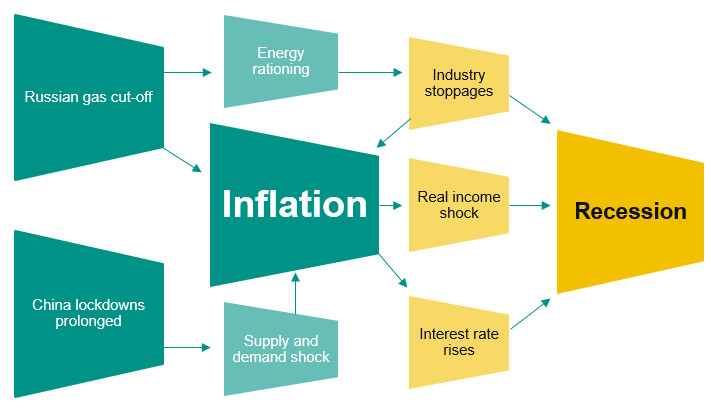

Recession Watch: Three key risks, and three crucial cushioning factors

Broadly, we divide recession risk into three buckets, which we describe in more detail below: 1. A Russian gas supply cut-off to Europe; 2. China lockdowns becoming more prolonged; 3. Inflation becomes an even bigger problem. This can by itself trigger a downturn via the hit to real incomes, or alternatively, this process is helped along by central banks in their attempts to return inflation back to target. (Note, the first two risks could feed into this third one). In the below schema, we illustrate how each of these recession risks interact, and the various pathways to a recession. These pathways are not set in stone; they are only meant to illustrate the various ways a recession could happen.

Risk #1: Russia cuts off the gas (35-40% probability)

We start with arguably the biggest looming threat to the outlook – at least for Europe – which is the ongoing risk of an abrupt halt in Russian gas supplies. We analysed this risk in more detail in our March Global Monthly, but we judge this risk to have risen materially since then, from around a 25% probability to a 35-40% probability. In late April, Russia halted gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria after these countries refused to settle gas payments in roubles. More recently, Russia halted gas supplies to Finland following its application to NATO. Currently, the risk of a broader stoppage rests largely on whether energy suppliers in other European countries would breach EU sanctions by complying with Russian demands to pay for gas in roubles. The European Commission has sent mixed messages on this topic, while Italian premier Draghi has said that the issue of sanctions compliance is up to member states to enforce. Ultimately, the issue is a political one, as the EU could agree on clarifications to sanction rules that enable continued purchases of Russian gas. In the meantime, the risk remains that other EU countries receive similar treatment to Poland and Bulgaria. Alongside this risk, the EU’s proposed embargo on Russian oil – yet to come into force due to Hungarian opposition – could also trigger a retaliatory Russian block of gas exports, something Russian deputy premier Novak suggested in March. All told, while still not our base case, we see a significantly higher risk of a Russian gas cut-off. We judge that this by itself would likely trigger a recession in the eurozone and the UK, with further price spikes in energy and spillover effects to other goods adding to the real income shocks we already see, and energy shortages leading to government enforced rationing and industry stoppages. Such a decline in activity in Europe would naturally have spillovers to the global economy, raising recession risk elsewhere.

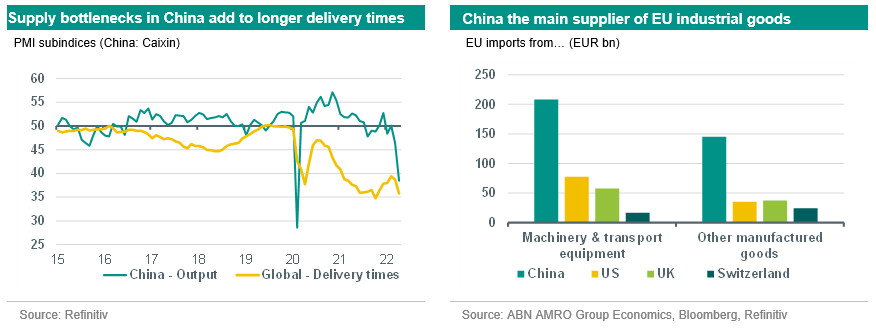

Risk #2: China lockdowns become more prolonged (25% probability)

A large swathe of China, covering approximately one quarter of the population as of mid-April, has been under some form of lockdown. While lockdown intensity varies significantly per city, and the overall intensity has declined somewhat of late, the impact is already becoming evident in the macro data. To start with the supply side, as analysed in our April Global Monthly, the broadening of lockdowns in March/April caused shortages of supplies and disruptions in production, alongside problems in truck transport and port congestion, particularly around Shanghai. This is also visible in recent macro indicators. The output and delivery times subindices of China’s manufacturing PMIs dropped sharply in March/April, while China’s industrial production contracted by 2.9% yoy and 7.1% mom in April. All of this is having a clear impact on global supply chains, with for instance global delivery times lengthening and a lack of materials and equipment hurting industrial production in the eurozone. Indeed, in the European Commission’s Q2 survey of industrial companies, 52% of all companies reported that activity was limited by shortages of materials and/or equipment. These problems were probably aggravated by the drop in production in China in April, as China is by far the biggest single supplier of intermediate goods and machinery imports to Europe (see figure below). After easing somewhat in late 2021, our global supply bottlenecks indicator has risen again in recent months, driven largely by falling Chinese output relative to developed economy demand.

Chinese lockdowns also add to global recession risks from the demand side. All demand indicators (PMI order components, retail sales, property sales, imports, fixed investment) were very weak in April. Consumer confidence has deteriorated and the unemployment rate in urban areas (6.1%) is almost back to the peak seen just after the initial Covid-19 shock in Q1-2020. While a technical recession by the strict definition (two consecutive quarters of negative qoq growth) is not very likely, given that China is still an emerging, high growth economy, the economic indicators for April can be described as ‘recession-like’.

Looking ahead, our base case assumes a gradual reopening of the Chinese economy (see Box p4), and government measures to alleviate bottlenecks in domestic transport and production. We also expect demand conditions to gradually improve compared to the trough seen in April, partly reflecting the further stepping up of targeted fiscal stimulus, monetary easing and a cautious relaxation in macroprudential policies including for real estate. As such, we expect growth momentum to improve in the second half of this year, although our 2022 growth forecast of 4.7% is almost 1pp below Beijing’s 5.5% growth target. Meanwhile, there is a significant risk that strict lockdowns lead to more prolonged disruptions to both supply and demand in China. This would keep delivery times in global supply chains high for longer, with further upward pressure on industrial goods’ prices. Chinese growth is estimated to be even lower (3.5-4.0%), adding to global recession risks from the demand side. That said, weaker Chinese growth would likely have a moderately downward impact on energy and other commodity prices, offseting upward effects on industrial goods’ prices.

Risk #3: Inflation hit to incomes/interest rate shock drives fall in consumption (30-40% probability)

The first two risks outlined feed into the much broader problem of inflation, which even without these risks crystalising, could by itself push advanced economies into recession. Across developed economies, real incomes are falling at their fastest pace in decades, although the problem is more acute in the eurozone and the UK where the difference between inflation rates and wage growth is most stark: in the US, inflation is running around 3pp higher than wage growth, while in the UK and eurozone that difference is nearer 5pp. This reflects the fact that inflation is still largely an imported problem in Europe; put another way, Europe is facing a large negative terms of trade shock via the surge in gas prices. The bigger scale of the shock in Europe is one of the reasons we expect less aggressive rate hikes by the ECB and Bank of England compared to the Fed. However, negative real income growth will ultimately act as a dampener on consumption on both sides of the Atlantic – notwithstanding the various cushioning factors that we describe below – and this could by itself push the economy into recession.

Central banks could deliberately – or accidentally – cause a recession

At the same time, central banks are beginning to step on the brakes in an attempt to lower the risk of inflation becoming more entrenched, with the Fed and Bank of England having already raised interest rates in recent months, and the ECB expected to begin raising its policy rates in July. This is feeding through to a significant tightening of financial conditions, with equity markets falling, and bond yields and mortgage rates rising. All of this puts yet further pressure on household incomes and business activity, through negative wealth effects and higher borrowing costs. The risks here are twofold. The first is that cooling growth might not be enough to keep inflation expectations well-anchored, meaning that central banks have to step harder on the brakes to deliberately trigger a recession. Fed Chair Powell has repeatedly flagged this risk, by emphasising the priority the central bank places on achieving price stability. The second risk is of a policy mistake. Interest rate changes are a blunt instrument that affect the economy with ‘long and variable lags’, as Milton Friedman once famously said, and as a result, central bankers are to some degree flying blind. In other words, it will be difficult to know when they have reached the sweet spot of keeping inflation expectations well anchored, while minimising damage to the economy. The risk then is that central banks over-tighten, accidentally causing a recession.

Excess savings, post-pandemic rebound, and fiscal policy are buffers against recession risk

So far we have outlined the major risks facing the global economy, but there are also a number of offsetting factors that – in our base case – will prevent economies from sliding into a recession. These cushions are so crucial, that in their absence we likely would already forecast a recession on the back of the inflation shock to real incomes alone. Although these cushioning factors give some cause for comfort, we emphasise that our conviction level is no longer as strong that these will be sufficient to offset the growth risks.

Cushion #1: Excess savings and confidence in job prospects

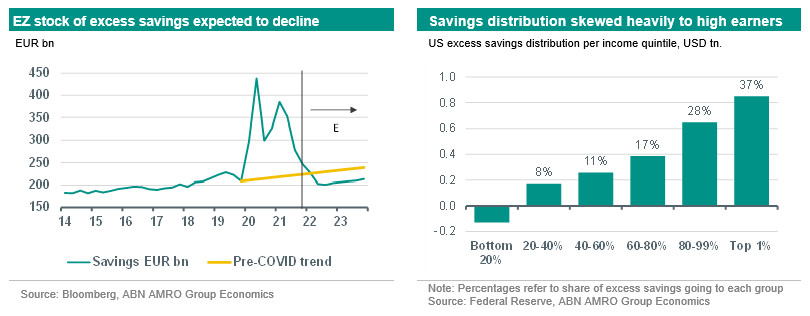

The most important, and most cited reason to expect consumption to continue growing despite real income falls, is the significant build-up in excess savings through the pandemic. On both sides of the Atlantic, savings rates surged during lockdown periods, largely because consumers were unable to spend on services in the way they would normally, although in the US this was accentuated by fiscal stimulus that overcompensated for income losses. In the eurozone, around EUR 880bn in excess savings built up between the start of the pandemic and the end of 2021, which is equal to around 14% of 2021 consumption expenditure by households (in the US, the equivalent figure was $2.4tn, or 15.2% of 2021 spending). Some of this excess has begun to decline, with savings rates dropping back below trend, particularly as inflation began to pick up in the latter half of 2021. However, the bulk of it remains, suggesting there is still considerable room for consumers to compensate for the hit from inflation to real incomes.

How long can this buffer last? Perhaps a few quarters, on our estimates. ECB data shows that about half of the excess in eurozone household savings is held in liquid cash and bank deposits, meaning it is readily available to spend, but the data also shows that the accumulation of savings is concentrated among higher-income households. For instance, households in the top 10% of the income distribution accounted for around half of the total rise in deposit flows between the start of the pandemic and mid-2021. The distribution is even more extreme in the US, with nearly 40% of excess savings accruing to the top 1% of earners, and the bottom 20% actually seeing a net decline in savings. Higher income households are in any case not liquidity constrained, so there would not be the same need to dip into savings to maintain consumption growth as for lower income groups. The lowest income groups have very limited (if any) savings buffer to offset the real income hit. This leaves the middle income groups, and it is they who we expect to make the most use of the excess savings buffer in dealing with inflation. Assuming a further decline in savings rates to near historic lows, we think aggregate consumption growth can continue to withstand the inflation hit for much of 2022, but that this buffer will be heavily depleted as we move into 2023. For the eurozone specifically, this estimate is based on assumed disposable income growth of 3-3.5% in both 2022 and 2023, and our expectation for inflation to fall back next year.

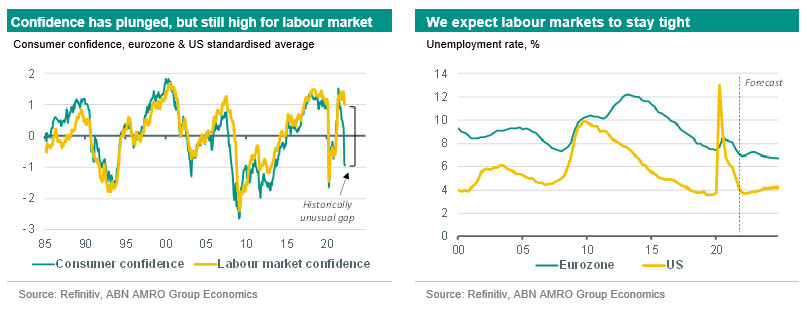

Another key assumption for households to utilise these excess savings is their continued confidence in job prospects. Historically, consumer confidence strongly influences saving habits; the more confident people are in the future, the more willing they are to spend rather than save. While consumer confidence overall has plummeted over the past few months, this fall has been historically unusual in that it has been almost entirely driven by inflation, with worries about unemployment still at very low levels. This is consistent with the tight labour markets we are seeing across developed economies. Our base case assumes that labour markets will remain tight. In the eurozone we continue to expect falls in the unemployment rate. In the US, we expect unemployment to start rising later this year, as interest rate rises begin to weigh on demand for labour, but we do not expect a surge in unemployment such that it significantly weighs on consumer confidence. With that said, there are risks to this view, and should employment prospects darken, this would also reduce the degree to which consumers deploy excess savings to maintain consumption growth.

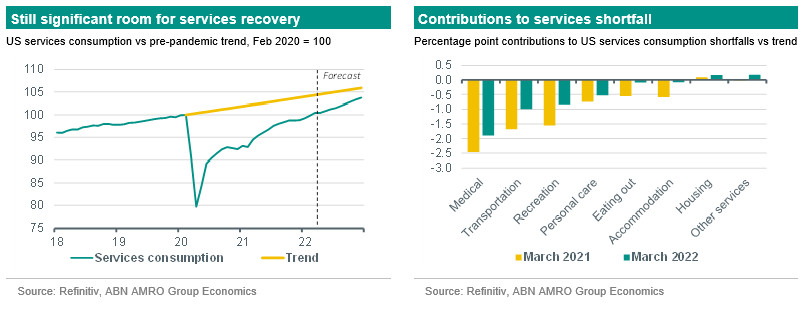

Cushion #2: Catch-ups in services demand and industry supply

One of the lingering effects of the pandemic is the continued shortfall in services consumption, and in industrial output relative to demand. The flipside of this is that there remains significant potential for rebound in these areas, and we expect the recovery trend we have seen so far to continue. On services demand, we estimate consumption is currently around 3.7pp below trend in the US, and perhaps double that amount in the eurozone. The shortfall – and therefore recovery potential, particularly in leisure and travel services – is greater in the eurozone due to the recurrent lockdowns throughout the pandemic (in the US, there were no further widespread lockdowns following the early 2020 episode). The services recovery should be significant tailwind for growth given that services makes up the bulk (60-70%) of private consumption. Even in the US, where the impact of the services recovery will be partly offset by an expected decline in goods consumption from above-trend levels, total consumption growth should remain positive. Following the expected rebound in consumption in Q2-Q3 in the eurozone, we expect growth to slow, as most (deployable) excess savings will have been spent by then. Still, consumption should continue to grow solidly next year, as employment is expected to expand and the gap between inflation and wage growth should diminish. In the US, in contrast, we expect consumption growth to fall below trend next year, as much tighter monetary policy leads to a modest rise in unemployment.

Industry is also likely to make a positive contribution to growth in H2 2022, as despite signs of cooling goods demand, there remain large backlogs of orders that will continue to support activity over the coming quarters. This backlog has been due to supply chain bottlenecks and shortages of labour, bottlenecks that we expect to ease as a base case in the course of the year. The European Commission’s recent survey of eurozone industrial companies showed that the volume of order books had reached the equivalent of 5 months of production in Q2 (see graph), which is the highest level since the start of the series in 1985. At the same time, the share of companies reporting that the level of production was not limited by any factors (eg. shortage of material and/or equipment or shortage of labour) dropped to an all-time low of 26. All told, in both the US and the eurozone, we expect industrial production and investment in machinery and equipment to bounce back as bottlenecks ease. However, subsequently, we expect the industrial sector and fixed investment growth to lose momentum again next year, as the global economy and world trade are expected to slow.

Cushion #3: Fiscal policy is helping in Europe, but not in the US

Although fiscal policy is unlikely to be anywhere near as active a support for growth as it was during the pandemic, we have still seen significant moves by governments in Europe to limit the fallout from the surge in energy prices. This has largely taken the form of tax cuts to energy and cash handouts to lower income households struggling to keep up with energy bill payments. While not as generous as the support we saw during the pandemic, this is still an important offset to the hit to real incomes. According to recent reports in the press, the European Commission is likely to propose soon that the suspension of the EU rules for government finances will be extended in 2023. In the US, however, fiscal authorities have been much more cautious, given that the inflation there has been more domestically-driven, while a consensus has grown among politicians that excessive stimulus during the pandemic was likely one of the causes of the current surge in inflation. Given this, we see very little prospect for the government to offer even piecemeal support for households in dealing with inflation. Instead, government efforts have been focused on relieving supply-side bottlenecks, including efforts to relieve port congestion, and the release of strategic petroleum reserves as a means of capping gasoline prices.

Conclusion

The current macro-economic environment is highly unusual. With an income shock of the magnitude we are seeing, we would typically forecast a recession right now. The significant cushioning factors we have outlined are a major offset that prevent us from doing so at this stage. However, if the risk factors we have outlined crystalise – for instance, if Russia were indeed to cut off gas supplies to Europe – even these cushioning factors would be insufficient to prevent advanced economies from sliding into a recession. (Bill Diviney, Aline Schuilling, Arjen van Dijkhuizen)