Global Monthly - How vulnerable is the economy to a sharp fall in house prices?

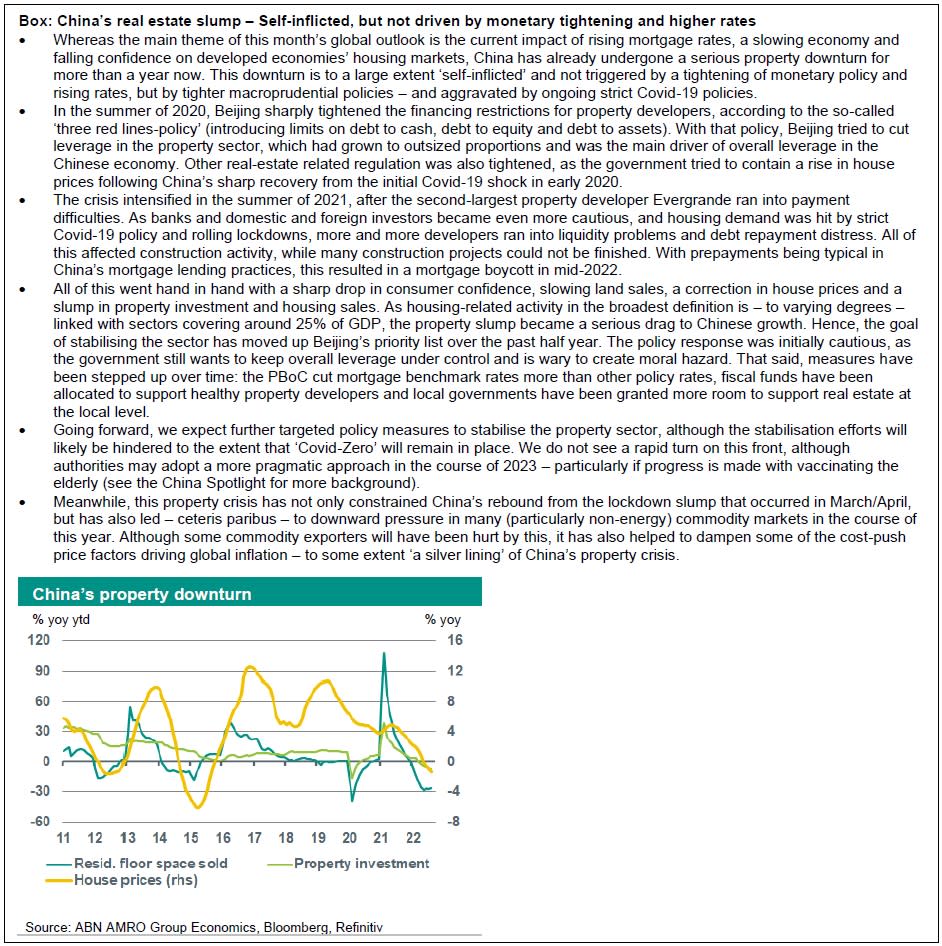

A potentially toxic cocktail for the housing market is emerging. Falling real incomes and fast rising interest rates are marking an abrupt end to the housing boom – aggravated by looming recessions. Our base case is for a moderate correction, but house prices could ultimately drop by 20-30 percent. The growth impact of deep housing market corrections would be strongest for the UK but milder in the eurozone and US. The drag on inflation would be biggest in the US. Even if there is a major correction, strong financial buffers would prevent this from being systemic. A notable exception is in China, with its mainly self-inflicted problems that are of a different nature.

Global View: A major house price correction could be in the offing, just as economies fall into recession

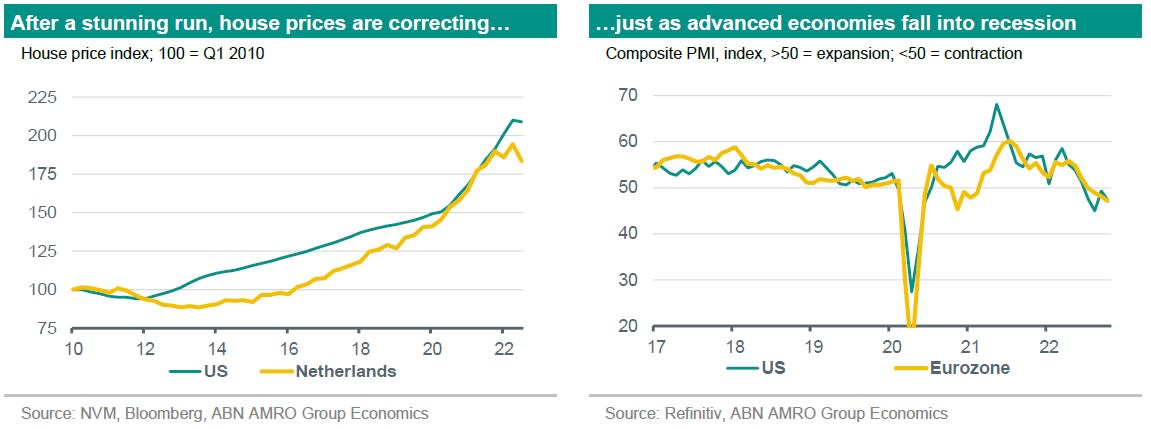

The news flow on the macro front has been mixed over the past month. The good news is that a mild start to the autumn and ample LNG supplies have driven a sharp decline in European gas prices. Meanwhile, in the UK, a change in government alongside significant policy U-turns has averted what could have become a major crisis. The bad news is that, as we warned in our past two Monthly publications, a European recession is already ‘baked in the cake’, and this was confirmed by the flash PMIs from October, which showed a continued decline in business activity, while consumer confidence also declined further. Against this backdrop of high inflation, rising interest rates and a looming recession in advanced economies, vulnerabilities in our economic system can come to the surface. The housing market could be one such vulnerability. While our base case is that house prices will decline mildly on balance, the economic uncertainties are sufficiently large to analyse whether major price corrections could occur and what the implications for growth and inflation would be.

Unaffordable homes

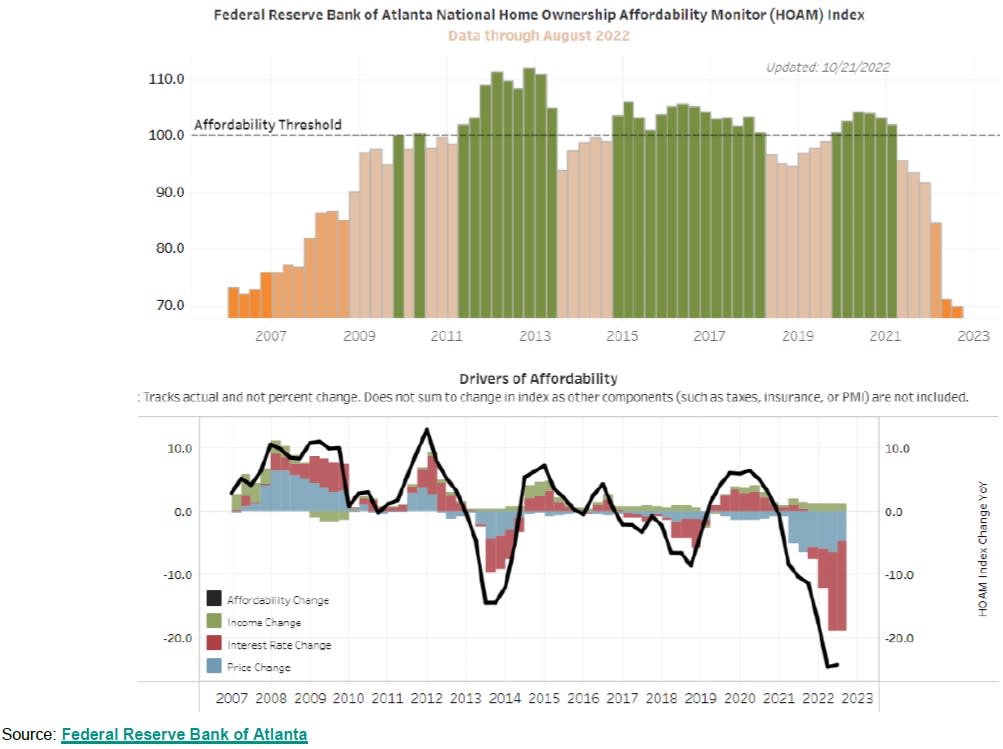

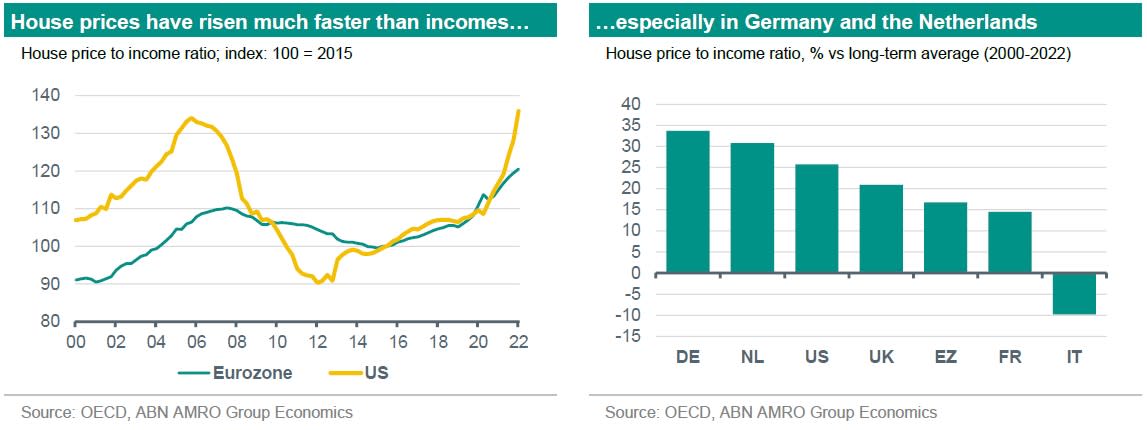

Home ownership has become much less affordable for most developed economies, and this was the case even before interest rates started to rise. House prices boomed during the pandemic on the back of lower rates, excess savings and shifting preferences. At the same time, some housing markets have a structural supply shortage. With the war in the Ukraine, energy bills in Europe have soared, lifting inflation and also inflation expectations. This, in turn, led to fast rising interest rates and a tightening of financial conditions as central banks responded. The Atlanta Fed’s Home Ownership Affordability Monitor illustrates this well for the US, and the picture is much the same on this side of the Atlantic.

House price growth has significantly outpaced income growth

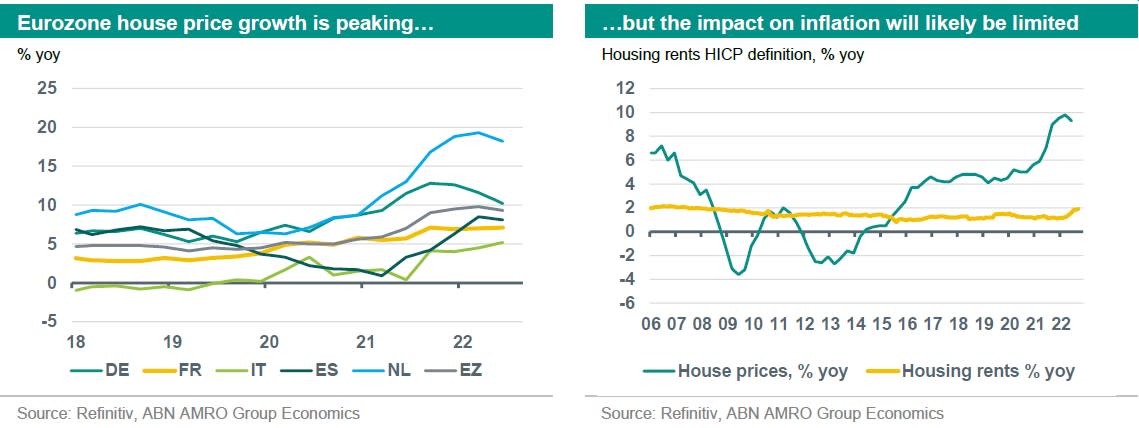

The rise in European house prices hovered between 4 and 4.5% yoy in each quarter of 2019, peaking at 9.8% in 2022 Q1. Particularly in Germany and in the Netherlands, house prices had already reached a level in the second half of 2021 at which affordability – and therefore purchases – were decreasing, even when mortgage rates were still low. Housing affordability – plotted below as the house price-to-income ratio – deteriorated sharply in both the eurozone and the US, but ratios are most out of line with historic averages in Germany and the Netherlands.

The inflation squeeze

Since the war started, housing affordability has deteriorated even further, as house prices continued rising while inflation eroded real incomes. Indeed, in most developed economies, income growth has failed to keep up with house price growth, reducing housing affordability and driving a fall in housing transactions, and subsequently in house prices.

Interest rate and mortgage rates

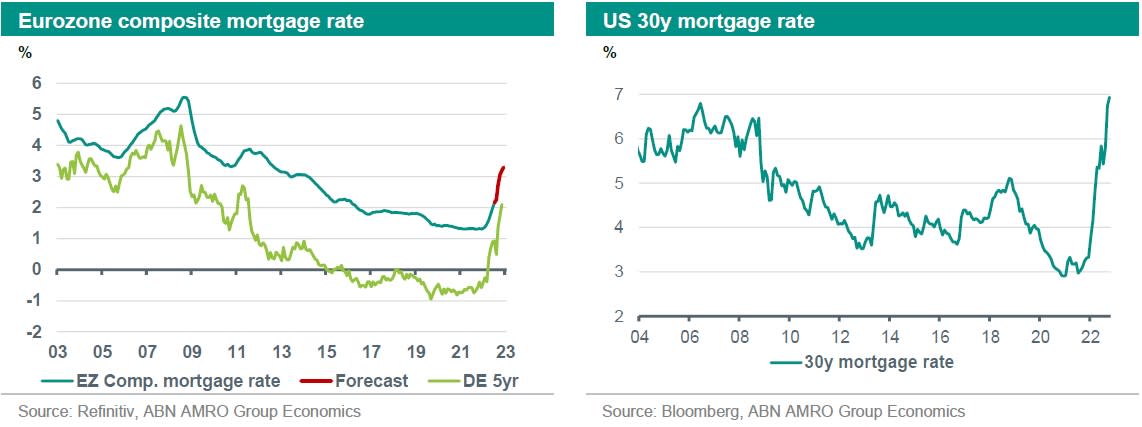

Interest rates rises, and subsequent mortgage interest rate rises, have clearly become another threat to housing affordability, as the Atlanta Fed indicator on the previous page shows. And interest rates are likely to rise even further, partly due to prior strength in the housing market, which continues to feed through to higher rents. September core inflation in the US, for instance, showed yet another increase in the housing related component of inflation (shelter). This happened against a backdrop of clear signals of cooling prices in other inflation categories due to the easing in global supply chain bottlenecks. The inflation rise since the post pandemic reopening in the US in the beginning of 2021 has already led to the Fed raising its policy rates 300 basis points this year, and we expect it to increase rates by another 125bp before year-end (see US chapter). Rising interest rates have also lifted mortgage interest rates, with the rate for 30-year US mortgages having doubled in a year’s time to 6.9%.

In the eurozone, mortgage rates have risen for different reasons. The ECB has also raised its policy rates to fight inflation, albeit by a smaller magnitude than the Fed so far (125bp in rate hikes so far). However, broader market rates have also risen on the back of rises in US rates early this year, as well as higher risk premia stemming the energy crisis and increased recession risk.

Looking forward, the downward impact of higher interest rates on the housing market has further to go. The ECB’s composite cost of borrowing indicator for households for house purchase has increased from a record-low of 1.30% in September 2021 to 2.3% in August 2022. Changes in ECB policy rates and government bond yields since then, suggest that composite eurozone mortgage rates will rise to around 3.5-4.0% by the end of the year, which would bring the total rise to around 2 percentage points (see graph).

Income effects

However, there are also some factors that will support household disposable income. Although record-high inflation will at some point affect home owners’ capacity to service their mortgage debt, strong labour markets and massive compensation schemes from governments are thus far limiting the fall in real incomes. This will support debt service capacity of households.

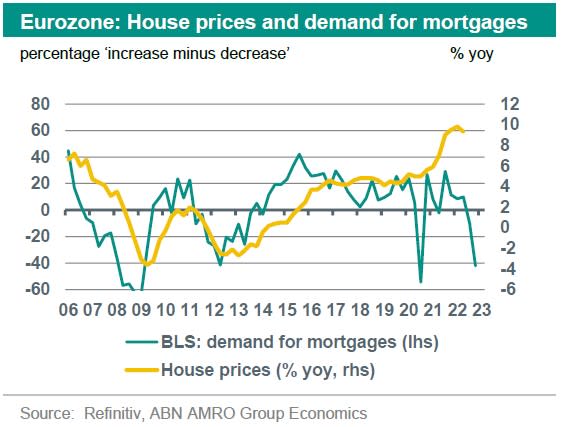

Mortgage demand drops ahead of price corrections

First time buyers and recent borrowers are most vulnerable to changes in mortgage interest rates. In the eurozone, the demand for mortgages – according to the ECB’s Bank Lending Survey (BLS) – has been an a strongly declining path. Indeed, in the most recent BLS, 42% of banks reported a substantial drop in demand for housing loans, which was the biggest drop since the first quarter of 2012 (excluding the pandemic period). The rise in mortgage interest rates as well as a drop in consumer confidence were mentioned as key factors behind reduced demand for housing loans. This is a clear signal that rising borrowing costs have made housing less affordable to newcomers, which also have to deal with the recent rise in house prices. Meanwhile, refinancing of mortgages has naturally become unattractive as mortgage rates have surged. Changes in BLS mortgage demand tend to be a good leading indicator for turning points in the housing market, now pointing to significant price corrections.

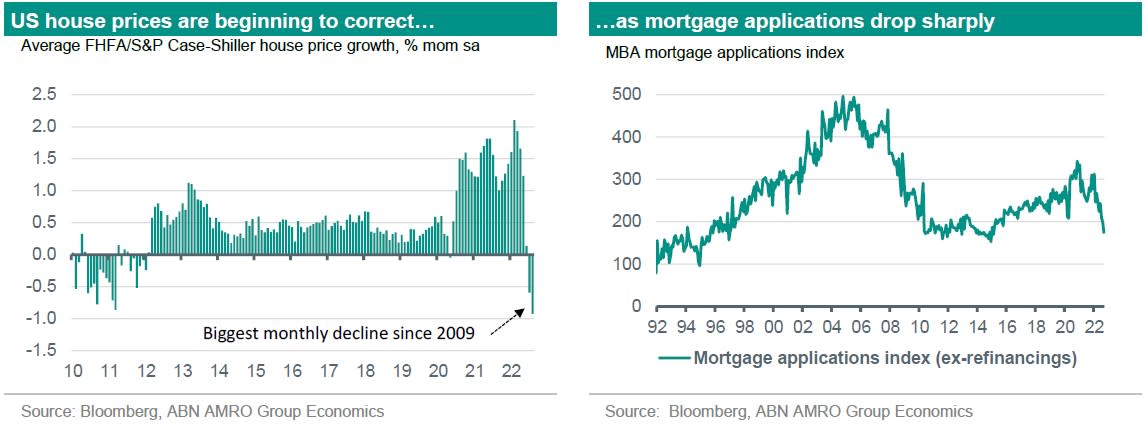

Also in the US, mortgage demand excluding refinancing has dropped significantly, about 50 percent (y-o-y). On the other side of the Atlantic, house prices are already starting to correct on the back of lower demand and reduced borrowing capacity. In August, prices for new homes purchases fell 0.9% (m-o-m), the biggest monthly decline since 2009.

Size of the potential drop

The increase in mortgage interest rates confronts home buyers with either higher monthly housing expenses, or a lower borrowing capacity. In the US, 30 year mortgages are now offered at 6.9%, more than twice as high as one year ago. This has reduced borrowing capacity by around one third. If we assume that no cushioning factors are in place that make up our base case scenario, a crude way to estimate the potential drop is to assume home buyers will keep their monthly expenses similar to the low rates era. This could imply a price correction of the magnitude of 25-30% in the US. This would almost take house prices back to pre-pandemic levels.

In the eurozone, a good way to estimate the size of the potential drop in house prices is to look at a model of the ECB. The ECB modelling outcomes suggest that housing dynamics in the eurozone are very sensitive to changes in mortgage rates. Indeed, the ECB’s model estimates that a 1 percentage point increase in mortgage interest rates from their historically low levels of the past few years, could result in a drop in house prices of around 9% after about two years. Given our expectation that mortgage interest rates will rise in total by around 2 percentage points by the end of the year, this would imply a drop of around 18 percent in house prices in the eurozone.

That being said, there are large differences between the various countries, due to local housing market regulation and tax regimes, while many countries suffer from a structural shortage of housing. These, but also other factors besides mortgage rates, also have a significant impact on house prices. For instance, there has been a notable shift in the preference of home owners during the pandemic towards larger houses. This shift will potentially cushion the blow. For these reasons, our base case is for a much milder correction in house prices than implied purely by the rise in mortgage rates, as explained at the end of this section.

Growth implications

Falling house prices lower growth via declining private consumption, wealth effects, as well as via consumer confidence. The latter is particularly impactful if home owners’ loan-to-value ratio rises above 100 percent, i.e. they are faced with ‘negative equity’ (for the time being, average LTVs are relatively low in most countries). The impact on growth differs per jurisdiction and is mainly driven by borrowing levels and the distribution of fixed versus floating rate mortgage rates. For fixed-rate mortgages, the share of home owners with short-term contracts that end this year or next matter significantly for the aggregate effect on costs of living and consumption. The shorter the durations of fixed interest rate periods, the more home owners are exposed to rises in mortgage interest rates.

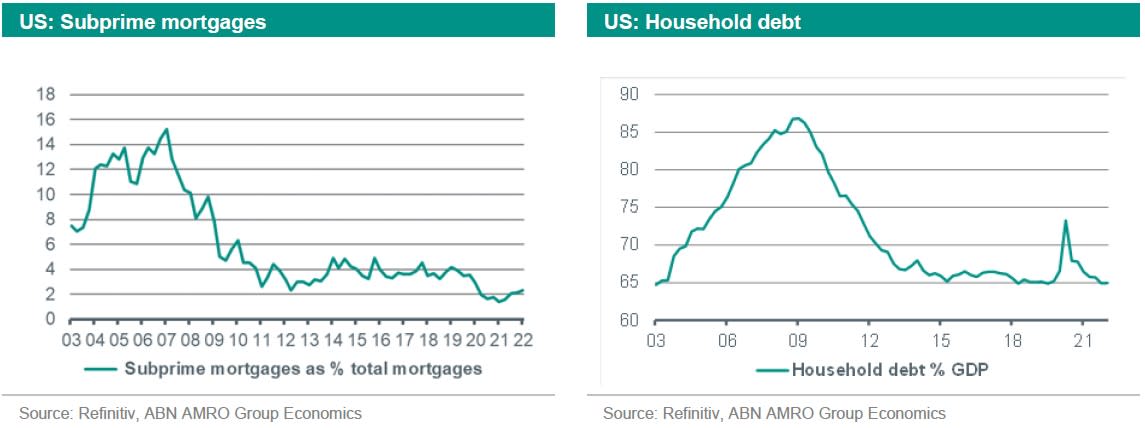

US impact: Mild

Macro prudential regulations since the global financial crisis have limited the build-up of household debt in the US. In 2021, household debt as a percentage of net disposable income was 101 percent in the US compared to 222 percent in the Netherlands. Also, most mortgages are typically fixed for 30 years, which acts as another layer of protection. Nonetheless, mortgage interest rate increases will still limit the purchasing power of new entrants to the housing market, and the resulting house price correction will still likely put downward pressure on consumption. In addition, home building is already seeing some impact from the downturn. Both of these factors will weigh on GDP growth over the coming quarters and are consistent with our expectations of a mild recession in the US.

UK impact: Severe

The growth implications of high mortgage rates and a more significant price correction will be much bigger in the UK than in the US. UK households are highly exposed to rising interest rates, given that mortgages in the UK are typically only fixed at relatively short time horizons. 25% of mortgages are immediately exposed as they are on variable rates, while half of the remaining mortgages on a fixed rate are due to expire in the next two years. Household debt as a percentage of net disposable income was at 148% in 2021, which is in between the US and the Netherlands. Given the political and economic turmoil in the UK, the sensitivity of a hit to real incomes from higher mortgage interest payments on top of existing hits from inflation and weak confidence, is one of the key reasons we expect a deeper recession in the UK. In the event of a major correction in the housing market, negative wealth effects would amplify the hit to real incomes, which leading to a greater loss of consumer confidence, which in turn would deepen the recession.

EU impact: Moderate

In the EU, the growth impact is likely to be more moderate, although northern European economies look much more exposed to a major house price correction than southern European economies. In Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, household debt is between 220-250% of net disposable income. In the Netherlands, the high debt-to-income is counterbalanced by an equally exceptionally high savings-to-income ratio from pension savings. That said, there is a risk that wealth effects from a steep house price correction will cause significant falls in consumption. This phenomena was seen in the aftermath of the financial crisis when wealth effects from house price declines tipped the Dutch economy into a double dip recession. Since then, regulatory changes have limited this risk, while Dutch households also tend to have very long fixed-rate mortgages, with many households having locked in low rates in previous years. For this reason, and as we elaborate on later, a major price correction is not our base case in the Netherlands.

In contrast, Sweden may be a notable exception to the moderate growth impact of a house price decline in the EU. 60% of Swedish mortgage owners have variable interest rates, on top of high debt levels, making the economy highly sensitive to a major house price correction. Finally, mortgage rates in many European economies are rising fast, but that rise is likely coming to an end. Looking ahead, we expect interest rates to peak around the end of this year, as recessions start to bite. Mortgage interest rates could increase a bit further, but are likely to fall back somewhat in 2023, in line with the expected move in government bond yields.

Inflation implications

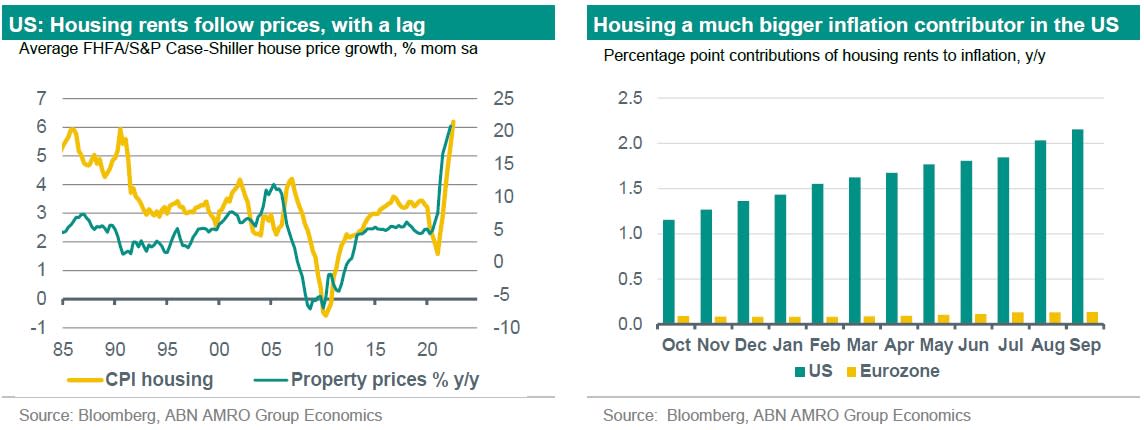

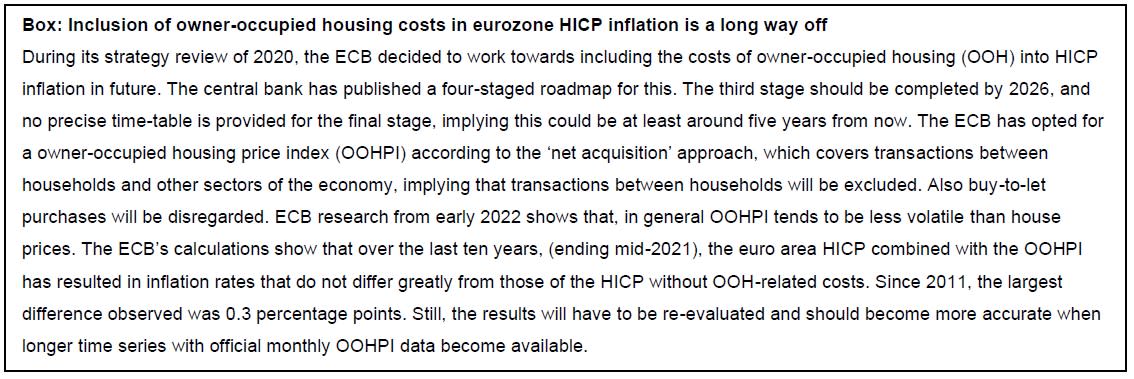

The direct impact of a major house price correction on inflation depends significantly on the relative weightings of housing rents in the inflation index. Housing rents here are defined as 1) actual housing rents faced by those renting accommodation; 2) owner’s equivalent rent (OER), which is an estimate of the foregone income a homeowner would receive from renting out their home. In the US, OER is included in the CPI, and as a result housing has a much higher share in the CPI than it does in the UK and the eurozone (in the Netherlands specifically, the CPI measure also includes OER, but not the HICP measure). Both the ECB and the statistics office in the UK have been working on new measurement instrument to take the owner-equivalent rent into account. Their first estimates show however that including owner-occupied housing costs are not creating huge differences in inflation.

On both sides of the Atlantic, rental inflation is a relatively slow-moving and lagging component of inflation, and institutional differences between countries (eg. rent controls) affect the correlation between house price changes and the housing rents component of the CPI.

US: Large impact

In the US, where shelter makes up one third of the CPI, a downward correction in house prices would have a significant dampening effect on inflation. Rental inflation is lagging in the US (as in Europe), but unlike Europe, high rental inflation has been a much bigger contributor to the current high inflation rate (adding 2.2pp as of September). As such, a house price decline should eventually put considerable downward pressure on US CPI inflation.

Eurozone: Mild impact

In Europe as a whole, housing rents are only about a tenth of the consumer price index. As such, a correction would only have a mild impact on inflation. Indeed, the link between house prices and housing rents according to the HICP definition is very weak in the eurozone (see figures below). The rise in housing rents (with a weight of 7.1% in the total HICP index) has increased from a low point of 1.1% in December 2021, to 1.8% in September 2022. However, the contribution of housing rents to total eurozone inflation was only 0.1pp in September. In the Netherlands specifically, the contribution is similarly small in the HICP measure, but bigger in the domestic CPI measure, where housing rents make up 23% of total inflation due to the inclusion of owners equivalent rent.

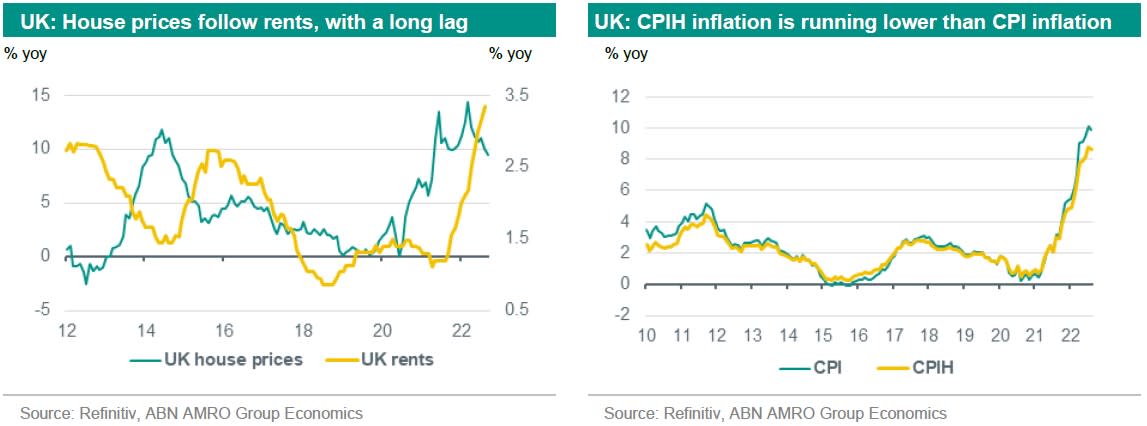

UK: Mild impact

Housing rents follow house price rises in the UK with a 12-18 month lag, but changes in rental inflation are historically much smaller in magnitude than those for house price inflation (both on the upside and the downside). In addition, the share of rents in the CPI is only around 9 percent (compared to 1/3 in the US). As such, rental inflation currently contributes just 0.36pp to CPI inflation, which in total is currently running at 9.9 percent.

The statistics office in the UK (ONS) has developed a new CPI measure (CPIH) which does include an estimate of owner-occupied housing costs. This is currently running considerably lower than broader CPI inflation due to the relatively smaller weight of energy and goods – which are responsible for the bulk of currently elevated inflation. The BoE’s target is in any case still the CPI, not the CPIH.

5 reasons for our base case: A mild house price correction with modest macro effects

The sharp rise in interest rates has taken its toll on housing markets globally, triggering inevitable comparisons with the Great Financial Crisis. Then, house prices dropped by 10% on average globally, but by more than 20% in many advanced economies. We judge that both the price correction as well as the implications for growth and inflation will be more moderate this time, for at least five reasons:

First, mortgage interest rate increases are rising fast, but that rise is likely coming to an end. Looking ahead, we expect interest rates to peak around the end of this year, as recessions start to bite. Mortgage interest rates could increase a bit further, but are likely to fall back somewhat in 2023, in line with the expected move in government bond yields.

A second related factor is that households are shielded from rising mortgage rates if their contracts have long durations. Particularly in the US, the vast majority of households – 79% as of Q2 22 – still have very long-term fixed rates (>15 years). As of Q2, around 2/3rd of households have mortgage rates below 4%. Also in the Netherlands, the average fixed-interest period of Dutch households mortgage loans was more than 15yrs at the end of 2021.

The strong increase in value during the pandemic is partly due to a shift in . This is particularly true for regions where people started working from home more frequently. The demand for house and outdoor space increased the most there. According to research, as much as half of the in the United States can be attributed to the shift to working from home. This apparent hunger for space should limit house price falls.

Fourth, there is a structural housing shortage in many developed economies. This shortage means that if prices start to fall, ‘hidden’ demand will come more to the fore, as housing becomes a little more affordable. Furthermore, higher construction costs and supply-side constraints limit the degree to which new housing can ease shortages.

A fifth counterweight is tight labour markets in combination with low unemployment, and other factors supporting incomes such as government support and energy saving initiatives. Governments have spent roughly 3-5% of GDP to compensate households and firms, and early evidence shows that households and firms are significantly reducing energy use by either behavioural changes or investments in insulation and renewable energy sources. Higher income households still have large excess savings to finance these investments, and most governments are already (or gearing up) additional support for lower income households.

Finally, even if a major price correction would occur, systemic risks from such a correction to the overall economy are much less than during the financial crisis. Macro prudential tools such as loan-to-value and loan-to-income ratios – and more prudent mortgage lending criteria more generally – have made households financially more resilient to shocks to the housing market. For the US, this is for example visible in the quality of mortgage credit that is now much higher than in the past, with a far lower % of subprime borrowers (see graph below). Also, capital buffers at financial institutions are stronger, and household debt to GDP is much lower than before the 2008 financial crisis. Indeed, the Bank of England’s latest stress test showed that UK lenders are able to absorb a 33% in house prices together with a rise in unemployment from 3.5 to 12 percent. Also in the Netherlands, the Dutch Central Banks stress test of households during the energy crisis shows only a 0.04 percent to 0.27 percent increase in mortgage defaults.

Nevertheless, while the system seems more financially resilient now than before 2009, inflation in combination with rising rates is causing financial vulnerabilities in many other parts of the household budget, such as the rising energy bill. A cost that is highly intertwined with affordability of housing.

Taking all of this together, we expect house prices to show a downward correction of some percentage points, something that has already started to happen across the globe. What is more, the fast correction we are recently witnessing in some countries probably reflects that sellers are currently more willing to accept a lower price. This is due to their price expectations (even lower prices in coming months) and the fact that some home owners might fear that their properties will even be in negative equity in a few months’ time. But the extreme price rises since the pandemic (Q2 2022 versus Q4 2019) – 39.7 percent in the Netherlands, 45.3 percent in the US and 23.6 percent in the UK – also imply that most sellers still sell their home with a profits, increasing acceptance of a lower prices. Once the fast, but limited, correction has happened, we expect that hidden demand will come forward as affordability increases.