Global Monthly - Are central banks doing enough to fight inflation?

The global macro picture has been a confusing one recently, with clear signs of recession contrasting with other signs of surprising resilience. We map out a range of macro indicators and make a judgement on which parts of the economy point to a recession, and which do not. We think recessionary forces will ultimately prevail, because we judge that central banks need recessions to be sure inflation falls sustainably back to target. Regional updates: We think core inflation has probably peaked in the eurozone, while in the Netherlands, we still see resilience in the economy despite the contraction in the first quarter. Spending cuts loom in the US, even if Republicans agree to raise the debt ceiling. China's economic rebound continues, but headwinds from property and US tech tensions are a drag.

Global View: Despite the mixed macro signals, central banks in any case likely need a recession

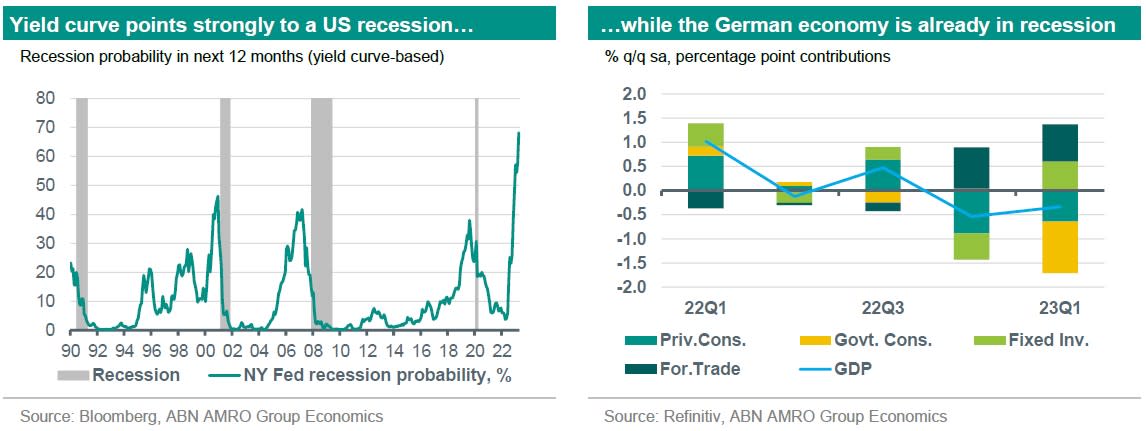

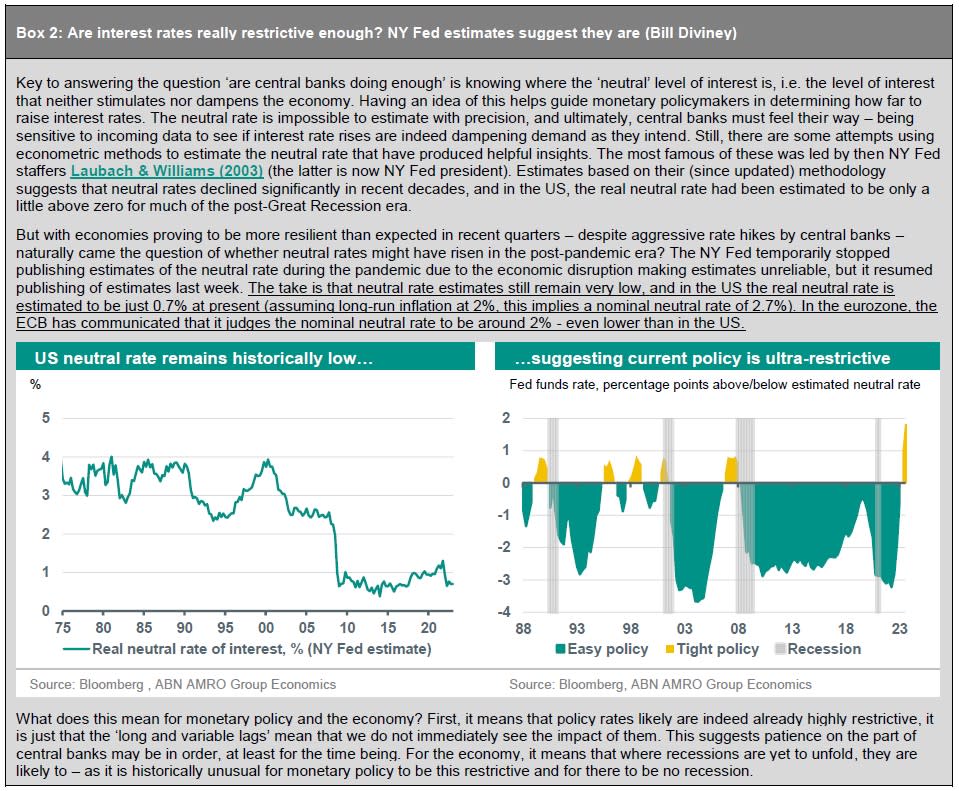

Central bankers have been at pains recently to remind financial markets that their job fighting inflation is not yet over – which was underscored by a shock UK inflation reading this week. While the Fed has sent the strong signal that it will likely keep rates steady at the 14 June FOMC meeting, and the ECB is likely approaching a peak in rates, the jury is still out on whether rates are being raised enough to generate sufficient economic weakness that brings inflation sustainably back to target. Complicating central bankers’ jobs are the mixed signals economies are giving out of late. Aggressive rate hikes have put a clear dampener on credit conditions, global trade and manufacturing are sending strong recessionary signals, and the US debt ceiling impasse poses an imminent threat to the US and global economy. Meanwhile, labour markets are still exceptionally tight, and parts of the services sector are still in post-pandemic recovery mode. Indeed, though it was confirmed this week that the German economy had already been in recession in Q4-Q1, the eurozone aggregate and especially the US have proven more resilient. In this month’s Global View, we try to make sense of the confusing picture by mapping out which parts of the economy point to recession, and which do not. Despite the pockets of resilience, we still think recessions are likely needed to bring inflation sustainably back to central bank targets.

Expansions do not die of old age – they are murdered by central banks

At a panel in early 2019, in response to former Fed Chair Yellen’s assertion that ‘expansions don’t die of old age’, her predecessor Ben Bernanke retorted: ‘I like to say they get murdered’. While a gruesome depiction of a central banker’s job, Bernanke was on the mark: unless triggered by a major exogenous shock (such as the most recent, pandemic-induced recession), recessions are normally caused by central banks raising interest rates ‘until something breaks’ – with the goal of ensuring inflation stays at (or falls back to) central bank targets. This is Central Banking 101.

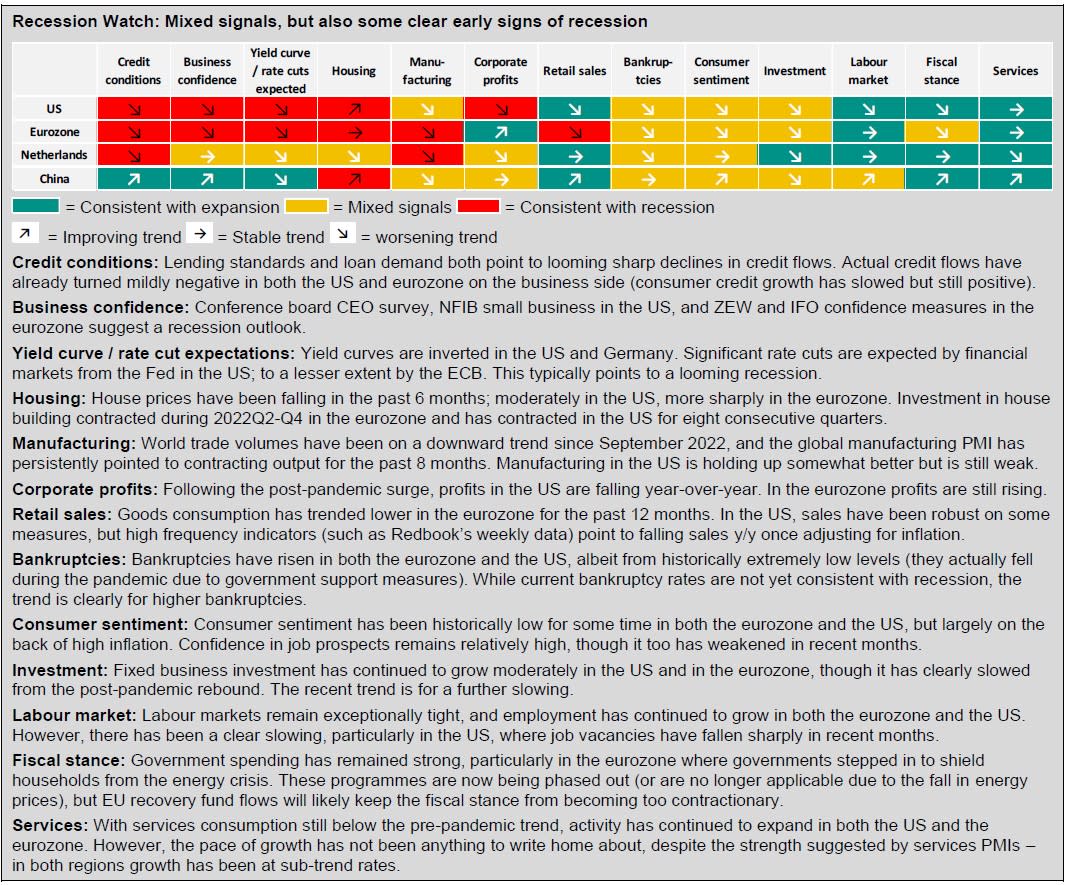

If a central bank’s job is to kill expansions that have got out of hand, how are they performing in their current tightening campaigns? In the below box, we map out various economic indicators across our main regions of coverage, and make a judgment over which are flashing red (pointing to recession), which are giving off mixed signals, and which suggest the expansion has further to run. Arrows denote recent trends in the data.

Our take is that while there are significant signs of imminent recession – particularly in the eurozone, where GDP was roughly stagnant in 2022Q4-23Q1 and Germany already entered recession – the overall picture is a mixed bag, suggesting the onset of recession could be further delayed. (Note: We include China in our heatmap due to its importance in the global economy, but it is subject to very different cyclical drivers and we do not expect a recession there.) As we will later argue, we continue to think that central banks will be determined to induce a downturn one way or another, for them to be confident that they have fought back sufficiently against the biggest inflation resurgence since the 1970s.

Three clear signs of recession: 1. It’s the credit conditions, stupid

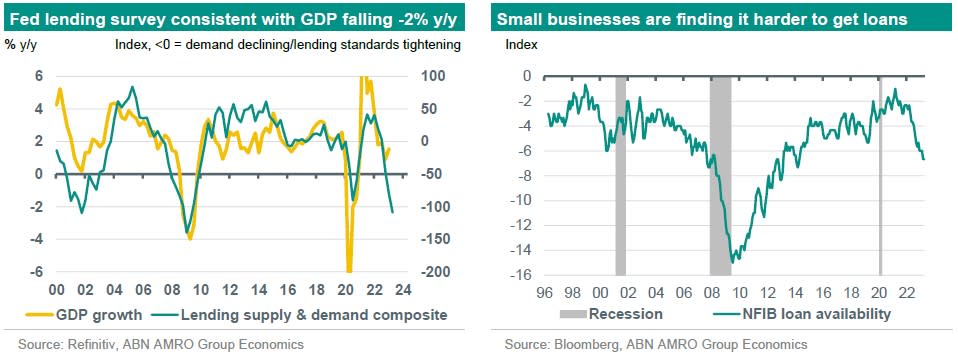

How do central banks cause recessions? By tightening credit conditions. And if there is one historically very reliable leading indicator of recessions that is clearly flashing red right now, it’s credit conditions (see also Box 1 of our April Monthly). Aside from higher rates making credit more expensive for businesses and households, concerns over the economic outlook have led to a tightening in both lending standards and declines in loan demand – in both the eurozone and the US – and this has been amplified by the banking sector turmoil following the failure of a number of regional banks in the US.

Less credit flowing into the economy means less money being invested by businesses or used for consumption by households, which inevitably weighs on activity. Based on historic patterns, the May update to the Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Survey is consistent with US GDP growth falling to around -2% y/y over the coming quarters, which is lower than our expected trough of -0.4% (expected in Q4). Weekly bank lending data from the Fed already points to modest declines in loans to businesses. Consumer credit is holding up for the time being, but over time we expect tighter standards and higher household savings rates to lead to declines here too. In the eurozone, banks sharply tightened lending standards on loans to companies and mortgage loans since 2022 Q3, while demand for loans has dropped to historic lows and monthly flows in loans to companies and household have slowed the most since the eurozone debt crisis (excluding the pandemic).

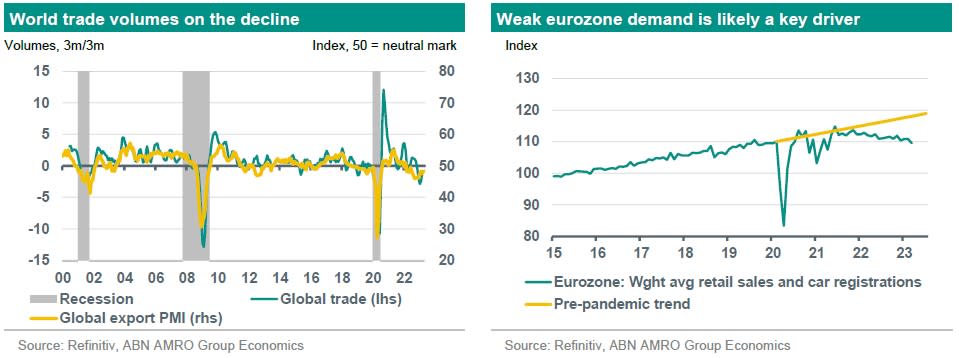

2. Global trade and manufacturing are in a clear downturn

After peaking last September, global trade volumes have been on a declining trend. In the past, such persistent declines in trade volumes have not occurred outside recessions. The weakness in global trade has led to stagnating industrial production in the eurozone and in the US, while in China, production was much weaker than expected in April. Leading indicators such as PMI new orders and new export order indices point to more pronounced weakness to come. A key driver has been the significant weakening in goods demand – particularly in Europe, where high inflation has driven a sharper decline in real incomes, leading to persistent falls in goods consumption over the past year. In the US, goods consumption has been more resilient, but there are also signs of softening demand (evident for instance in Redbook weekly sales data).

Disturbances in China related to Zero-Covid (broad lockdowns in October/November followed by a messy exit in December) have also contributed to global trade weakness in late 2022, although according to CPB the reopening rebound has likely been a key factor in the uptick seen in world trade volumes in March. Still, with monetary policy expected to stay well in restrictive territory in advanced economies – keeping a firm lid on goods demand – the prospects for a sustained near-term recovery in global trade and manufacturing look slim.

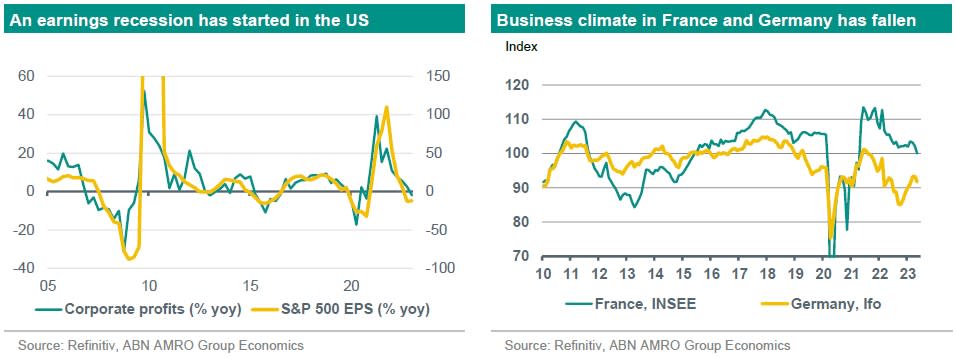

3. Business confidence is weak and corporate profits are declining (in the US)

Various measures of business confidence signal recession on both sides of the Atlantic. The Conference Board’s CEO survey in the US shows 87% of respondents expecting a shallow recession over the coming year. The NFIB small business survey index has fallen back below the pandemic lows. Corporate profits are now declining in the US following a post-pandemic boom in earnings. In most of the big eurozone countries business confidence is below the long-term average and declined further in April-May. In both regions, bankruptcies have been on a rising trend, albeit from historically very low levels. Bankruptcies are likely to continue rising in the coming quarters as tight financial conditions and weakening demand put increasing pressure on business solvency.

Can the services recovery or the tight labour market prevent a recession from unfolding?

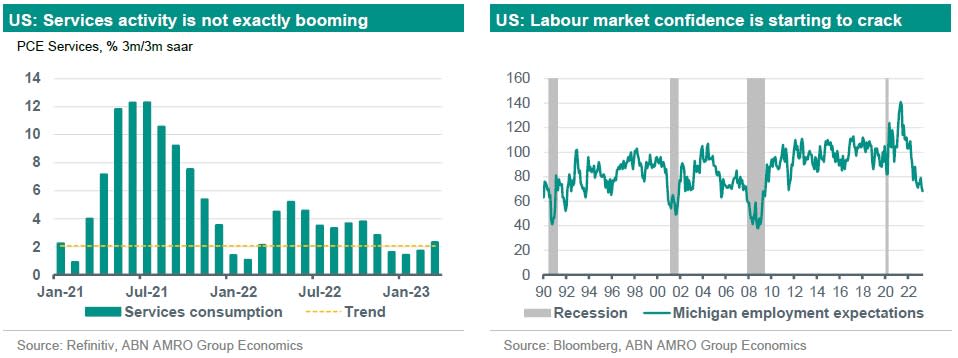

Among the areas of the economy clearly still flashing green are the services sector and the labour market – and these are reasonable factors to point to in making the case for no recession. Services consumption in both the eurozone and the US is still running around 2.5pp below the pre-pandemic trend, suggesting that there is still some room for catch-up growth. And a key factor supporting consumption broadly is that labour markets are exceptionally tight, meaning that any rise in unemployment is likely to be relatively modest compared with previous economic downturns.

While we think these are going to be crucial factors cushioning economies going forward, we see them as preventing downturns from turning more severe rather than preventing them altogether. Despite there still being room for services to recover from the pandemic, the sector will not be immune to the same headwinds that are weighing on goods consumption: namely tighter credit conditions and the hit to real incomes from high inflation. Indeed, though services consumption has continued to grow in recent quarters, the pace of growth has hardly been anything to write home about given the catch-up potential – we estimate services activity grew at a below-trend rate the eurozone and broadly at trend in the US in Q1. So, while the services economy is by no means weak, it is not exactly booming either.

A crucial underpinning for consumption has been confidence in job prospects. Indeed, broadly weak consumer confidence has been largely the result of high inflation, with the employment subindices of consumer surveys showing much stronger confidence in job prospects. While jobs growth has remained robust for the time being in both the US and the eurozone, however, consumers are starting to worry more about the outlook. For instance, the Michigan employment expectations subindex fell to the lowest level since the 2008-9 recession in May. As labour markets continue to cool, and particularly as unemployment begins to rise, consumer caution – and spending cut-backs – are only likely to increase.

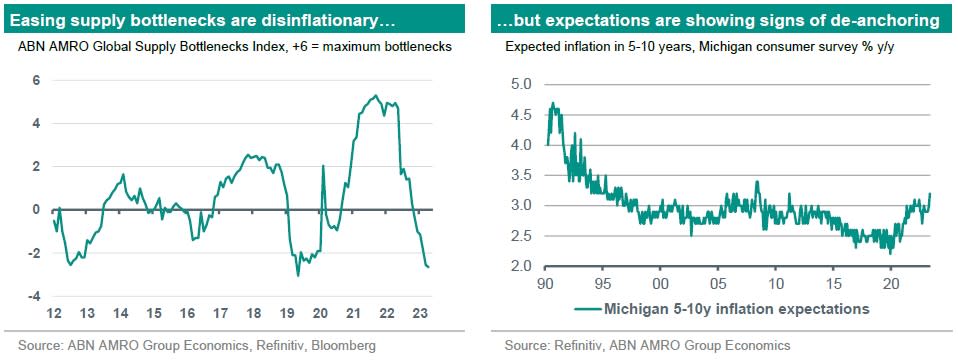

‘No landing’ isn’t impossible – but we would give it a low probability

Another case against recession is that inflation may continue to fall – all the way back to central bank targets – without a rise in unemployment, leaving central banks able to then cut interest rates to support continued growth in the economy. This is the so-called ‘no landing’ or ‘immaculate disinflation’ thesis. There are some good reasons to believe in such a scenario. First, much of the inflation we have seen was triggered by supply-side bottlenecks – disruptions to freight shipping, the war in Ukraine and Europe’s energy crisis – rather than being the result of major excess demand in the economy. This argument is much more applicable to Europe than it is to the US, where goods consumption surged to well above trend levels on the back of ultra-generous fiscal stimulus. Still, if we take as a given that most of the inflation surge is explained by the supply side, then the recent normalisation in supply bottlenecks – including the easing energy crisis in Europe – should now support a significant fall in inflation, even in the absence of a recession. The case for this was made by Bank of England Deputy Governor Ben Broadbent at the Bank’s May policy meeting.

A second major factor supporting this thesis is the sharp fall in job vacancies in the US – from a peak of around 12 million to 9.6 million as of March – which has occurred so far without a rise in the unemployment rate. That the Fed has seemingly been able to kill so much excess demand for labour without significant job losses so far is indeed remarkable (1).

While we do not dismiss the ‘no landing’ scenario outright, we do see a relatively low probability of it materialising, for two reasons. The first concerns inflation expectations. Even if the initial driver of the inflation surge was supply-side driven, supply-side issues getting resolved does not necessarily take us all the way back to square one (the pre-pandemic era of below target inflation). That is because the post-pandemic inflation has clearly led to a rise in longer run inflation expectations, which – against the backdrop of a tight labour market – has led to higher wage demands and higher wage growth. Indeed, the latest Michigan survey of 5-10 year inflation expectations – closely watched by the Fed – rose to a new post-pandemic high of 3.2% in May. Meanwhile, unit labour cost growth has surged in the US, and has been running at 6% y/y for the past two quarters. A similar development is taking place in the eurozone, where wage growth has jumped in response to the energy crisis, without a corresponding rise in labour productivity. Unless businesses accept a fall in their profit margins, these costs will ultimately be passed on to consumers, potentially sparking a wage-price spiral. As such, although in big picture terms we expect inflation to continue falling in both the US and the eurozone, wage developments mean that inflation is unlikely to fall fully back to target without a meaningful rise in the unemployment rate.

Secondly, while excess demand in the labour market has eased in the US without a rise in unemployment so far, there is no guarantee that this will continue – and historically, it is unprecedented for such a large drop in labour demand to occur without accompanying job losses. Fed Chair Powell acknowledged this himself in a recent post-FOMC press conference, while naturally expressing the hope that the Fed might achieve what had not been possible in the past.

What does all of this mean? If recessions do fail to materialise over the coming months, we think it is unlikely inflation will fall fully back to central bank targets by itself (2). Central banks may then need to tighten policy further in order to induce the necessary economic weakness (=recessions).

Conclusion: Central banks are likely to favour price stability over preventing recession

If we take the view that inflation cannot fall fully back to target without a recession, and if we think central banks are genuinely committed to bringing inflation fully and sustainably back to 2%, then a recession looks unavoidable. A statement that Fed Chair Powell has repeated verbatim in each of his post-FOMC press conferences over the past year has been:

“Without price stability, the economy does not work for anyone. In particular, without price stability, we will not achieve a sustained period of strong labor market conditions that benefit all. The burdens of high inflation fall heaviest on those who are least able to bear them.”

This statement makes crystal clear that – when push comes to shove – the Fed will favour achieving its 2% inflation target over stemming a rise in the unemployment rate, because ultimately, fulfilling the second pillar of the Fed’s mandate (maximum employment) also depends on price stability. Indeed, the fact that the Fed is signalling that rates at the very least will stay in highly restrictive territory for at least the coming two years despite Fed staff forecasting a US recession, points to how determined the Fed is to get inflation back to target. For the ECB, where the inflation target is the only explicit goal of its mandate, this is likely to be even more so the case. Indeed, despite the German economy falling into a recession, there has been no let-up in hawkish comments from ECB Governing Council members.

(1) An alternative explanation is that the high level of vacancies was to a large extent due to reallocation of people between various sectors after the pandemic. So, lower vacancies could also mean the reallocation is making progress instead of demand for labour falling due to monetary policy tightening and the economic slowdown.

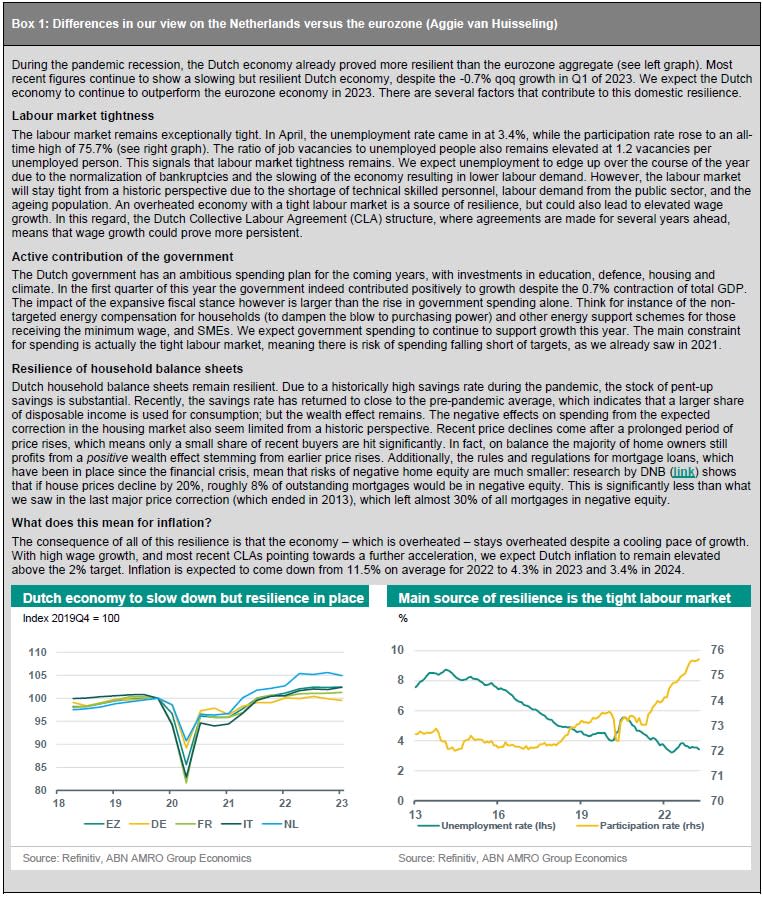

(2) We see a higher risk of this happening in the Netherlands, for instance, where our base case is for no recession. This is because ECB policy calibrated for the broader eurozone may prove to be insufficiently tight to bring inflation fully back to target in some specific countries. See also Box 1.