Global Monthly - A softer landing – but still a landing

The major economies diverged in the first half of 2023, but overall, activity continued to expand, and inflation fell further back – albeit still well above central bank targets. Unexpected strength in the US has led us to drop our call for recession. We still expect tight monetary policy to drive a US slowdown later this year, and to continue to weigh on the eurozone. Even with rate cuts next year, tight monetary policy is likely to limit any post-slowdown rebound. Spotlight: Will we face gas shortages in Europe next winter? We take stock of the energy crisis. Regional updates: We expect prolonged weakness in the eurozone to eventually push inflation lower, while in the Netherlands we expect only modest growth following the technical recession in H1. In the US, bank lending standards are not quite as tight as we thought, but will still drive a slowdown. China's reopening rebound continues to fade, and headwinds have intensified.

Global View: Even with a softer landing, tight monetary policy will still weigh heavily on growth

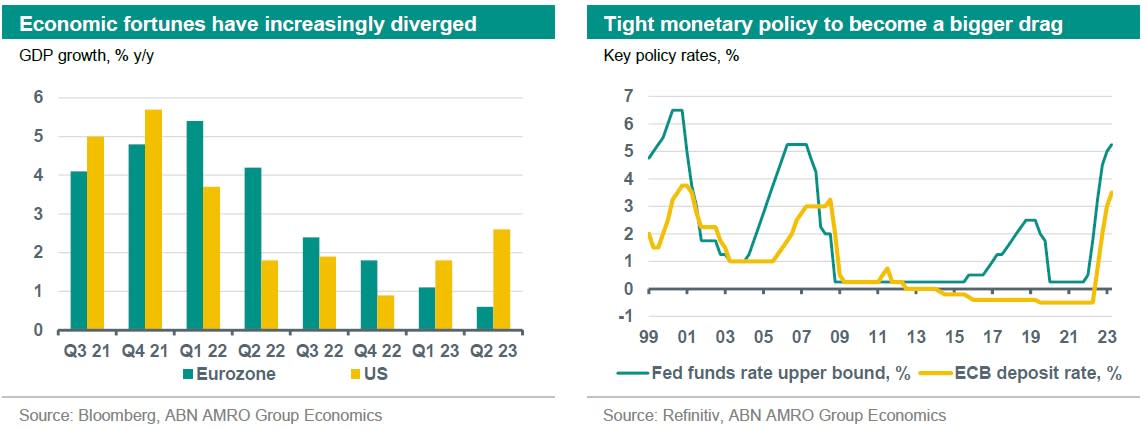

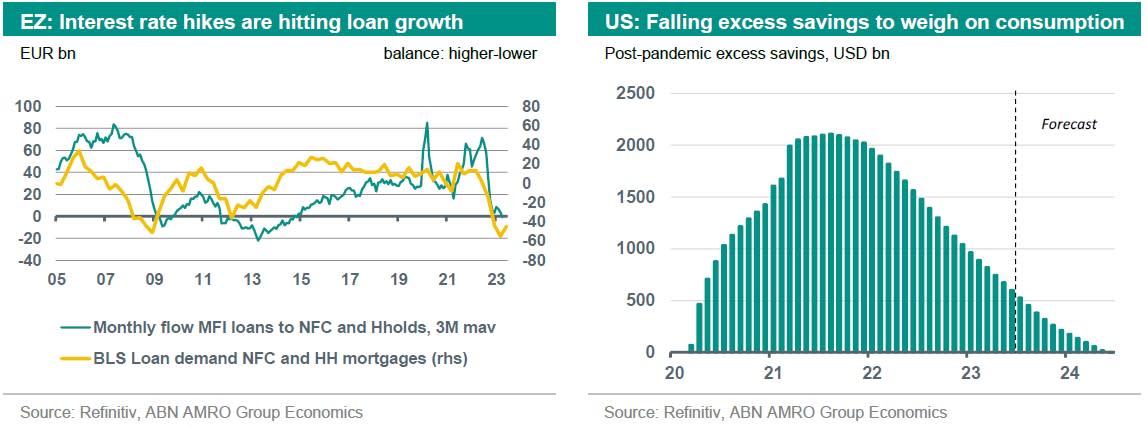

Since our last Global Monthly before the summer break, the fortunes of the world’s major economies have increasingly diverged. The US has exhibited unquestionable and unexpected strength; the eurozone has been weak, albeit not as weak as we thought; and China’s post-pandemic recovery has disappointed. How have these divergent trends affected our growth outlook for the remainder of 2023 and into 2024? In terms of the main drivers, our growth outlook is mostly unchanged from June. We continue to expect the headwinds from tight monetary policy and dwindling excess savings to weigh on advanced economies over the coming quarters, while in China, we expect the government to limit the downside of the faltering recovery, but do not see a stimulus bazooka on the horizon. Still, the underlying strength evident in the US economy has led us to revise our recession call to one of a sharp slowdown, while we have made more backward-looking changes to our GDP forecasts for the eurozone and China. Looking beyond the near term expected weakness, we take our signal from where central bank policy is likely headed. Although continued disinflation means that interest rates have likely peaked in most advanced economies, we still expect tight monetary policy to exert a drag on growth for at least the coming year or so. As such, while growth should bottom out early next year, we do not expect a spectacular rebound to follow.

Taking stock of H1 2023: Divergent trends, but both growth and disinflation have continued

With Q2 data now in for most major economies, it is clear that despite the strong headwinds, the global economy continued to expand in the first half of 2023, and this was fortunately accompanied by a further decline in inflation. However, this big picture assessment masks major regional differences. The clear star performer has been the US: Q2 GDP growth not only surprised to the upside, with the economy expanding at an above-trend 2.4% annualised pace, but Q1 was also revised significantly higher, to 2% up from 1.3% in the third estimate. The strength was driven by continued resilience on the part of the US consumer, but a rebound in fixed business investment in the second quarter also came as a surprise given the weakness in global trade and manufacturing, and higher financing costs on the back of Fed rate hikes. While we continue to think this degree of strength is unsustainable in the current high rates environment, it nonetheless points to a degree of confidence and resilience in domestic demand that – combined with the continued decline in inflation – we now judge will help the US avoid a recession.

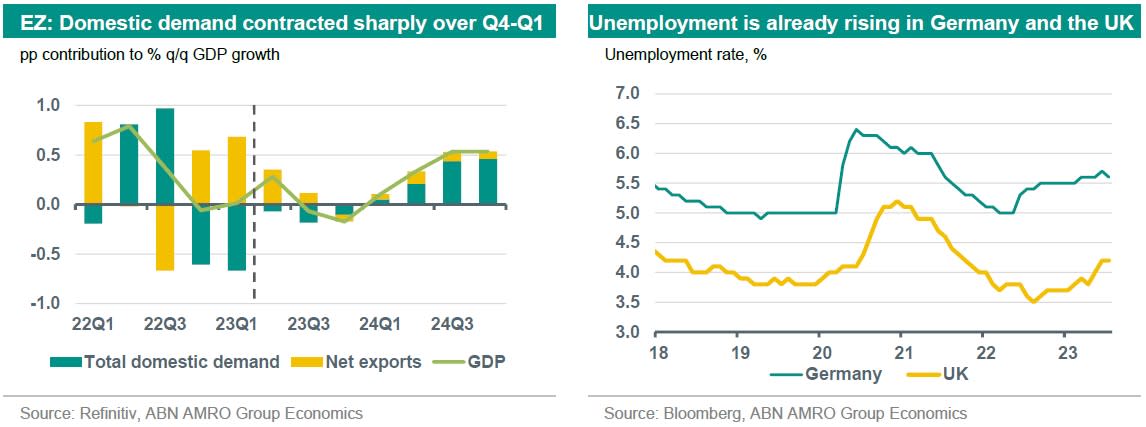

In the eurozone, in contrast, while the mild technical recession of Q4 22-Q1 23 was revised away in the latest GDP report, the details were hardly something to celebrate: domestic demand remained very weak, as consumer spending continues to be weighed by the aftermath of the energy crisis. Ominously, much of the strength was instead driven by falling imports, while export growth was flat over the same period. Finally, in China, the economy continued to normalise and expand following the end of the zero covid policy, but after a strong start of the year the recovery has been much weaker than expected, and the headwinds from the weak property sector and (at best) stagnating global trade and industry appear to be intensifying.

Why haven’t recessions materialised in (most) advanced economies?

With some important exceptions (including here in the Netherlands, as well as Germany), most advanced economies have managed to dodge the recessions that were widely predicted late last year – and in the case of the US, by a very wide margin. What went wrong? (Or right?)

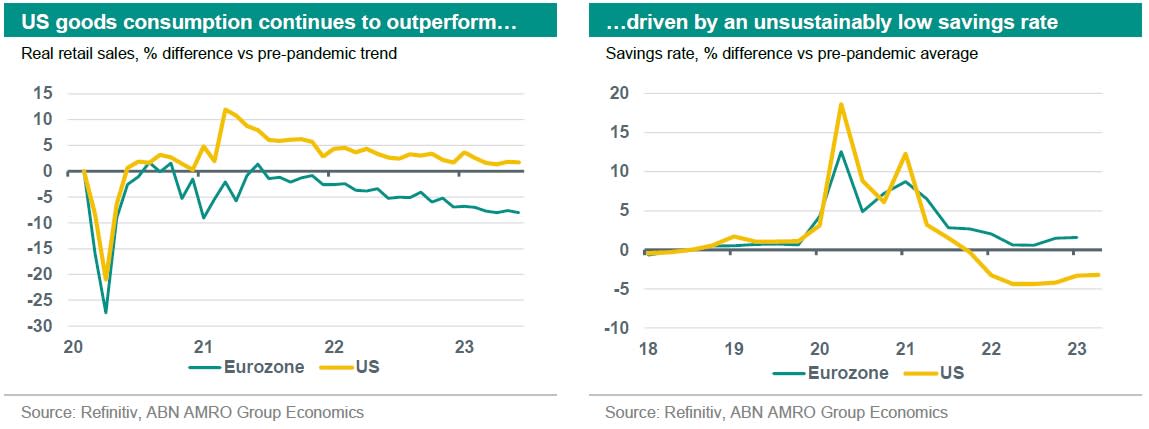

We would highlight two important factors. First is the strength of household and business balance sheets, which appears to be cushioning against the impact of high interest rates for longer than we predicted. This is a much more dominant factor in the US, where stimulus during the pandemic was much more generous, and where the (unsustainably) low savings rate is enabling consumption of goods that is still above the pre-pandemic trend (durable goods consumption specifically is around 6pp above trend). In the eurozone, in contrast, goods consumption has fallen to well below trend in recent months, while the savings rate has picked up.

Something common to both regions, however, is a still relatively low level of bankruptcies – an after effect of the massive support governments provided to businesses during the pandemic. While bankruptcies have risen from the extraordinarily low levels of the recent past, so far they have only normalised rather than soared to recession-like levels.

The second important factor is what has come to be called the ‘rolling recession’: the idea that different sectors are going into recession at different points in time, but that these sectoral downturns are not sufficiently synchronised for the entire economy to be in a recession. This is arguably particularly evident in the eurozone, where goods consumption and manufacturing have been exceptionally weak, but this has been offset by the post-pandemic recovery in services. This narrative is also applicable to the US: the most interest rate sensitive part of the economy – housing investment – has contracted for eight consecutive quarters. But house building is now a much smaller part of the economy than it was before the global financial crisis, and so the impact of this decline on the broader economy is much smaller than it was back then.

Forecast update: US recession dodged, but growth to weaken; eurozone to stay weak

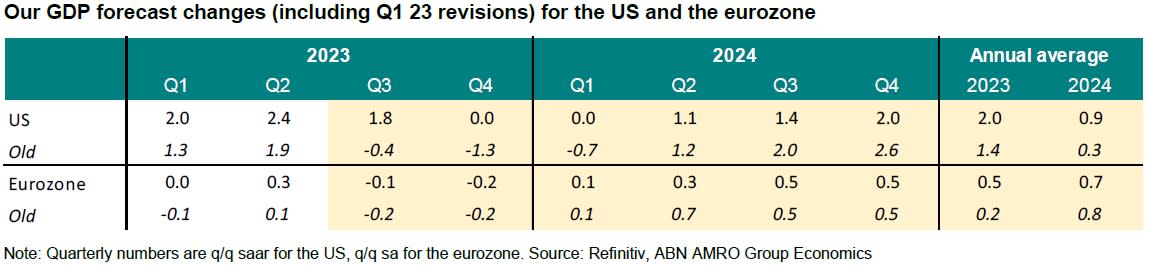

The biggest change to our forecasts concerns the US. Our base case no longer foresees a mild recession, but instead a slowdown and a stagnation in output around the turn of the year. The headwinds facing the economy remain very much intact, both from tight monetary policy and the running down of excess savings. As such, we see a slowdown as a question of ‘when’ rather than ‘if’. Even so, we also think the underlying strength of the economy means that it is likely to avoid a simultaneous and broadbased decline in output that would meet the recession definition. Our updated scenario now reflects this, while also keeping the expectation that the headwinds will eventually have a significant dampening impact on economic activity. Indeed, we judge such an outcome as necessary if inflation is to fall fully and sustainably back to the Fed’s 2% target.

Previously, we expected the economy to contract over Q4-Q1 23, with a significant rebound in activity in the second half of 2024. We keep this profile broadly intact, but we have ‘softened the edges’ so to speak: the growth trough is now more shallow, but also the rebound is less pronounced. Net-net, this still means a significant upgrade to our annual average growth forecast for 2024, which goes to 0.9%, up 0.6pp from our most recent projection of 0.3%. Our forecast for 2023 also rises, to a large extent on the upward revision to Q1. See table below.

In the eurozone, we continue to expect a prolonged period of economic sluggishness, with GDP contracting moderately or being close to stagnant during the second half of this year and the first half of 2024. It is possible that volatility in GDP means this does not meet the technical recession definition of two consecutive quarterly contractions. However, the big picture is one of weak domestic demand that is increasingly seeing the effects of the sharp rise in interest rates over the past year. Indeed, activity and survey data published since the start of the summer indicates ongoing weakness ahead. Although GDP growth in 2023Q2 came in higher than expected (at 0.3% qoq) the expansion was largely due to exceptionally high growth rates in Ireland (+3.3%) and Lithuania (+2.8%). Excluding these two outliers, eurozone GDP would have expanded by only 0.1% in Q2. While we lack the full breakdown by expenditure for Q2, domestic demand contracted sharply in 2024Q4 and 2023Q1 (-0.6% and -0.7%, respectively), and our monthly activity tracker suggests domestic demand continued to contract in Q2. These are starkly different trends to those seen in the US, where domestic demand remains strong.

All told, following the upward revision to Q1 GDP growth (to 0.0% from -0.1%) and the upside surprise to Q2 growth, we now expect annual growth to increases to average 0.5% in 2023, up from our earlier estimate of 0.2%. Meanwhile the average for 2024 has edged lower to 0.7% from 0.8%, as we have lowered our forecasts for 2024H1 somewhat.

Unemployment still expected to rise modestly in both the US and the eurozone

A key part of our updated forecasts – and critical to fixing the inflation problem – is that despite the growth upgrades, we still expect modest rises in unemployment in advanced economies over the coming quarters. In some countries, such as in Germany and the UK, the unemployment rate has already begun rising, and elsewhere labour market tightness has eased significantly. Even in the US, which has a particularly strong labour market, employment growth has come down markedly, and the job vacancy to unemployed ratio has fallen from a peak of 2.0 to 1.6 as of June, retracing a half of the rise seen since the pandemic (in 2019, the ratio averaged 1.2). With wage cost pressures elevated and demand expected to weaken (in the US) or to stay weak (eurozone), we expect this to trigger increased layoffs and reduced hiring. However, the starting point of extreme labour market tightness means that we are unlikely to see the kind of large scale layoffs we normally see in a downturn. While wage growth looks to have peaked, it remains elevated and above levels consistent with 2% inflation. A modest rise in unemployment should help to ease wage pressures, and in turn help to bring inflation fully back to 2% targets.

Regarding China, following disappointing Q2 and monthly activity data, we already cut our annual growth forecasts for 2023 and 2024 last month, to 5.2% (from 5.7%) and 4.8% (from 5.0%), respectively. The reopening rebound in services and consumption has faded since Q1, while headwinds from slowing external demand and property have intensified, and extreme weather in the summer has added to these headwinds. Further impacting confidence and sentiment is the scarring from previous stringent policies (Zero-Covid, regulatory crackdown). With the July data generally disappointing and signs of distress in the property sector ongoing, risks remain tilted to the downside, even though the PBoC continues with piecemeal monetary easing and the government is stepping up targeted support in line with our expectations.

Why we still expect a sharp slowdown in the US, and continued weakness in the eurozone

With advanced economies proving to be resilient despite the surge in interest rates over the past year, it is reasonable to doubt whether high interest rates will have a dampening impact on activity going forward. However, monetary policy works famously with ‘long and variable lags’ – taking up to 4-5 quarters for the impact to be felt. What makes things even more complicated with this rate hike cycle is that there are reasons to expect lags could be shorter, as well as longer. Lags could be shorter, because financial markets move to price in rate hikes long before they happen – leading for instance to much higher mortgage rates even before central banks started raising interest rates. On the other hand, the lag for other parts of the economy could be longer, due first to the longer-term fixing of interest rates (eg. in many countries, the typical mortgage is fixed for a longer time period than in the past), but also due to the strength of household and business balance sheets, which has likely insulated many from the impact of rate rises so far. Indeed, on the latter point, as mentioned previously we think excess savings in the US especially have enabled the consumption binge to go on longer than we thought.

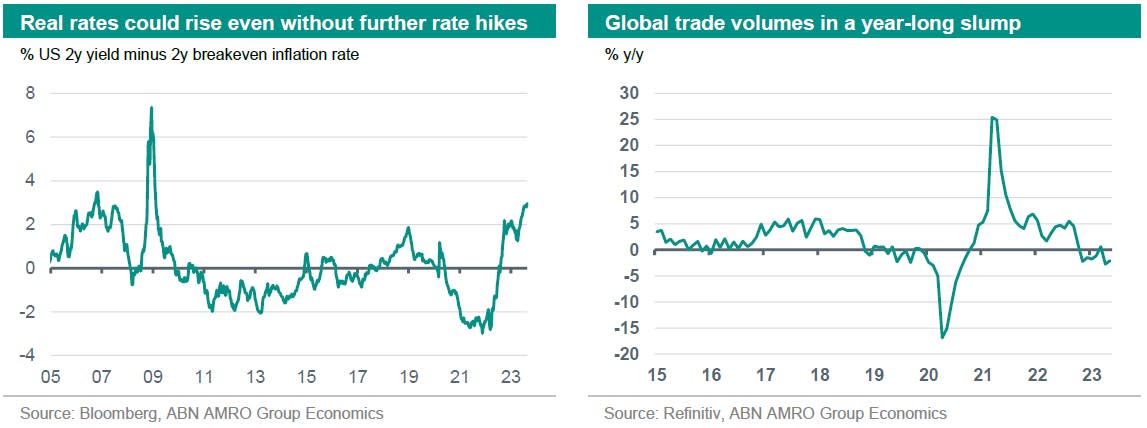

However, we do see increasing signs of an impact from rate rises in the form of falling loan growth, and we expect that impact to intensify over the coming quarters. In the US, we estimate that excess savings are close to being exhausted (for lower income households that is likely already the case), and that this will drive a correction in goods consumption. Higher rates are also leading to a further tightening in bank lending standards, even if that tightening may not be as stark as suggested by the headline surveys (see US section). Finally, real interest rates have been depressed until relatively recently by elevated inflation. As inflation falls further, this will continue to push real rates higher, even without further rate rises by central banks. Indeed, this is one of the main reasons we expect the ECB and the Fed to start cutting rates in March next year.

What are the prospects for recovery next year?

While we expect advanced economies to be weak over the coming quarters, we continue to expect a modest recovery in the second half of 2024. This is likely to be helped by modest interest rate cuts by central banks, as well as a recovery in real incomes as inflation falls back. Both of these naturally therefore hinge on the inflation outlook, which itself depends on labour market tightness continuing to ease. Without this, central banks will be unable to lower interest rates and tight monetary policy will continue to constrain economic growth.

Even in our base case of continued falling inflation and modest rate cuts, monetary policy is likely to remain relatively restrictive even into 2025. We expect the fed funds rate to fall back to 3.50-3.75% by the end of 2024, and the ECB deposit rate to fall to 2.00% – still above estimated neutral rates for the US and the eurozone. Given this, we do not expect a sharp rebound in growth next year, but instead a return to near-trend rates of growth. This will also likely keep a lid on any recovery in global trade and industry, which has been in a downturn for almost a year now. In the near-term, we do expect a bottoming out in global manufacturing, but we do not foresee a strong recovery until sufficiently low inflation enables central banks to cut rates back to neutral levels – likely in 2025. (Bill Diviney, Aline Schuiling, Arjen van Dijkhuizen)