ESG Strategist - What does the NZBA exodus tell us about banks’ climate ambitions?

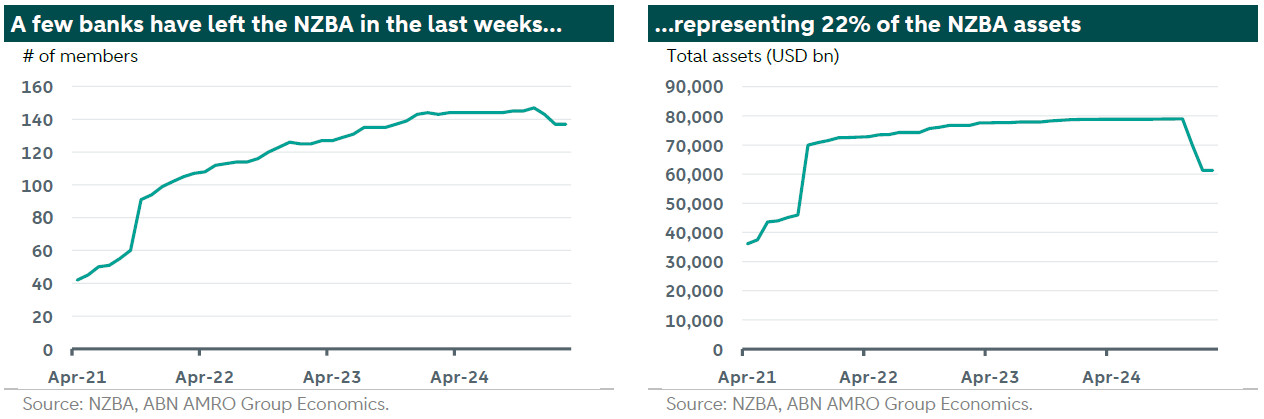

Several prominent US and Canadian banks have announced that they are leaving the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), which is a coalition aimed at aligning the banking sector with global climate goals, that has gained significant traction over the last few years. The departures in December 2024 and January 2025 represent a decline of 22% in the total assets of the banks participating in the alliance, while these banks also represent 12% of the assets of the entire global banking system. Given the size and systemic importance of these banks to the global economy, their departure was perceived as meaningful and triggered a lot of questions on the future of the banks’ climate ambitions. In this piece, we aim to explore these questions and what their departure might mean for the energy transition.

Large US and Canadian banks have left the NZBA in the past few weeks, ultimately resulting in a 22% decrease in the alliance’s total assets

We argue that the main reason for their exit was the shift in climate policy in the US under the new Trump administration

And indeed, as we have seen, the new government aims to scale back on clean energy, while supporting the development of oil and gas projects

This could lead to lower profitability for green projects and more attractive investment opportunities for fossil-fuel projects

The systemic importance of these banks and their resulting importance in the global economy and society may serve as argument that they should pursue the most profitable investment, which often means they need to be aligned with political agendas…

…however, this is only a valid argument if maximizing welfare would be the same as maximizing profits, which some economists argue is not the case

Furthermore, if banks do not invest in green initiatives, they expose their portfolios to higher climate-related risks, which has a long-term impact in profitability…

…but under an environment where climate policies are rolling back, transition risk is very low and banks might not necessarily fear exposure to physical risks

As a result, a “green bank” in a “brown environment” may also risk becoming a laggard

Ultimately, the decision of these banks to withdraw from the NZBA reflects how strongly banks’ climate strategies are tied to governments’ agendas

Why did these banks leave the NZBA?

The real reason for their departure is unclear, but one can think of a few potential explanations. In our view, the most important one is the shift in climate policy in the US under the new Trump administration and the resulting positive economics for fossil fuel energy investments (and consequently, negative economics for renewable/clean energy).

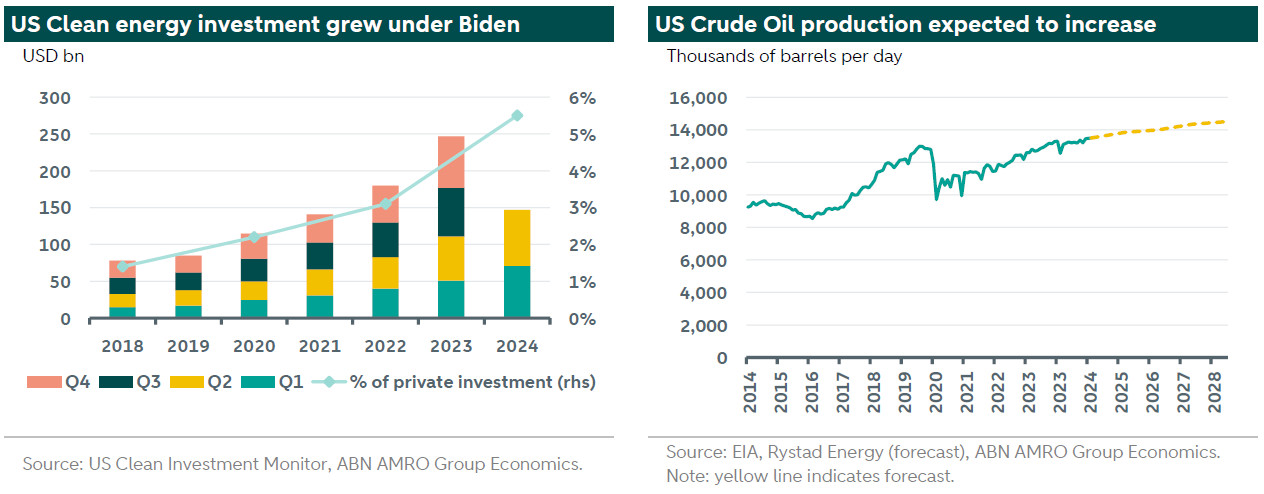

Under the Biden administration, the US focused on developing subsidy schemes to encourage investment in the climate transition and consequently help the country achieve its Nationally Defined Contribution (NDC) targets set out in 2021. The NDCs are targets linked to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement. These schemes significantly improved the economics for investments in clean energy, and have resulted in more funds towards the sector (see chart below). It was also following the more pro-climate environment in the US that the six largest US banks (mainly: Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo) decided to enter and sign the NZBA.

With Trump winning the elections to become the 47th president of the USA, it was widely expected that he would once again withdraw the country from the Paris Agreement, as was previously the case in his first term of office (read our previous piece here). And indeed, as expected, Trump announced several policies that will likely hamper the climate transition immediately after taking office.

The President decided to immediately pause disbursement of funds by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and bipartisan infrastructure law, which combined sum up to USD 280bn of loans for green infrastructure put under review. Furthermore, he also announced the freezing of new and renewed leasing for offshore wind projects and a review of all existing onshore and offshore wind projects. This announcement increases the risk of delays for upcoming renewable energy projects, while also creating legal risks for new projects, which all add to additional costs to the developers. According to Rystad Energy, nearly 25GW of offshore wind (65% of the US projects in development) are unlikely to progress under the Trump administration. All of these factors reduce the profitability of clean energy projects. In one of our previous notes, we showed that a one year delay in a project before it becomes operational can result in around 100bps decrease in an offshore wind project’s IRR, all else equal (see here).

The departure of large North-American banks from the NZBA seems to indicate that these parties have anticipated that the tide for clean investments is turning.

Meanwhile, the new President’s agenda (which includes Trump’s promises to “drill, baby, drill”) focuses on fast-tracking permits for new fossil fuel infrastructure. Trump also lifted a 2024 pause on approvals for applications to export natural gas facilities that was put in place by the Biden administration. These pro-fossil fuel policies are likely to boost profitability of oil and gas related projects, encouraging banks to increase lending to these companies due to high demand for funding and lower (short-term) credit risk.

It is not as straightforward as it seems

It is important to remind ourselves that banks play an essential role in society, particularly globally systemic banks, such as the US ones that withdrew from the NZBA. Hence, their financial health is of economic importance, which could involve pursuing the most profitable investments. At the same time, if those profitable investments are towards carbon-intensive projects, there is a risk that in the long-term these institutions will also be negatively impacted by heightened climate risks (more on this below). For example, the ECB estimates that under a “late push” scenario, combined losses of EU banks could amount to EUR 65bn by 2030 ().

Under this logic, a by Nobel prize winner Hart and Zingales (2017) argues that companies should not pursue profit maximization, but rather focus on maximizing welfare – which are not the same thing, as commonly assumed. This argument stems from the assumption that shareholders are also concerned about ethical and social aspects, which are inseparable from money-making. As such, would maximising profit and minimising climate damage (a negative externality) be interconnected activities, then shareholder welfare is not equivalent to market value. A question that arises from this is: where should shareholders’ fiduciary duty lie, is it within maximizing profits or welfare? Important to note however that the conclusion from the authors only holds if the shareholders feel responsible for the (negative climate) action. An argument can be made that perhaps this is not always the case – particularly in the US. In this case, welfare and profit maximization would still be the same.

Furthermore, if we add to the equation that employees also enjoy non-monetary benefits from their jobs (job security, personal satisfaction, etc), the survival of the company might become a priority concern. Hence, the authors argue that if investing in clean energy is less profitable than investing in fossil fuels (as it currently tends to be), companies may have the incentive to invest in non-climate friendly activities “if that is the only way for the company to keep going”. Additionally, they acknowledge that the welfare vs. market value discussion ignores “the possibility that, as shareholders become poorer, they may put less weight on ethical concerns, that is, morality is a normal good”. However, the high inflation over the last years and the resulting erosion of consumers’ purchasing power, could have made this a very likely possibility. Nevertheless, it is important to note that “the first ECB economy-wide climate stress test showed that the short-term costs of a green transition would be more than offset by the long-term benefits”.

If we assume that there is indeed a distinction between welfare and market value, and that shareholders favour the former, another important point to consider is whether companies have the ability to pursue these climate-friendly strategies. This might be a challenge in an environment where government policy has shifted in the other direction. A few examples: very recently, a that American Airlines “violated federal law by filling [its workers pension plan] with funds from investment companies that pursue ESG goals”. In March 2023, a group of US General Attorneys sent a letter to asset managers “asserting breaches of their fiduciary duties and violations of antitrust law as a result of the asset managers’ ESG investing” (see ). Not exclusive to the US, in the Netherlands, the right-wind party VVD has put forward a motion asking pension funds to prioritize financial returns, which they claim to be negatively impacted by the practice called “impact investing” (see ). In all these cases, the company’s ability to pursue welfare maximization was barriered by legal challenges.

This is therefore an example of how important (and influential) the external environment is for both, banks and their shareholders. Hence, there is clear connection between governments’ agendas, positive profitability of projects, and banks ability to pursue green strategies. We explore that issue in more detail below.

Is it all about the external environment?

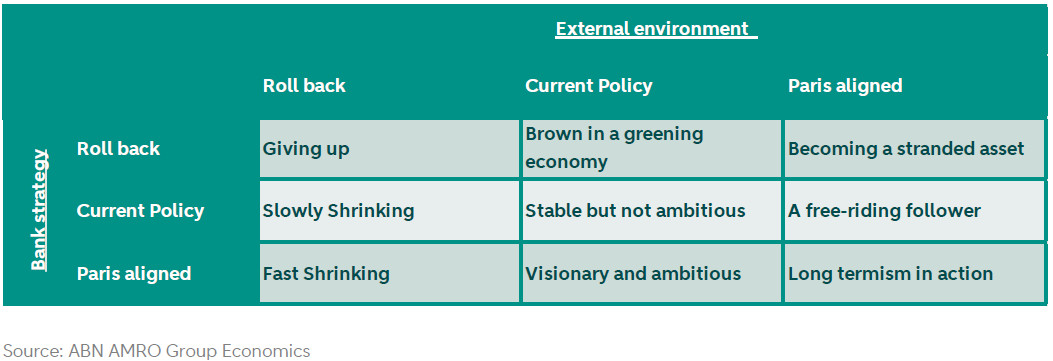

A bank that does not align its strategy with the external environment (climate policies and government ambitions) could be risking losing competitiveness and becoming a laggard. There is therefore a tension that arises from the speed of the climate transition and the speed of the transition of a bank’s balance sheet. This is exemplified in the table on the next page. Would a bank decide to pursue an ambitious (Paris-aligned) climate strategy in an environment where policymakers are rolling back on climate commitments, it could be faced by a fast shrinking balance sheet. On that note, research has shown that investing in green initiatives helps to mainly reduce banks’ transition risks. But if climate policy is rowing backwards (which means transition risk is very small or inexistent), then the most important climate risks to which banks are exposed to is physical risks. However, show that weather disasters have insignificant or only minor effects on bank performance. That is because banks tend to reallocate higher capital out of unaffected countries towards disaster-affected countries where local credit demand is high due to the need for reconstruction. This disasters often increase loan demand and boost bank profits. This once again reinforces that if the external environment is climate “unfriendly”, then a bank that pursues a green strategy may be risking becoming a laggard.

On that same note, would governments quickly push the transition forward, a bank which is not Paris-aligned can risk having to quickly decarbonize its balance sheet and be faced with holding a fairly amount of stranded assets. The ECB estimates that transition risk-only can be responsible for combined annual losses of up to EUR 65bn, a result of corporate probabilities of defaults (PDs) nearly doubling by 2030 under a “late push” transition scenario.

The roll-back in US climate policy was therefore a trigger for US banks to also align their strategy with this new external environment. This was a move that also ensured the financial health of their operations, which is, as we previously noted, of vital importance also for society and economy as a whole, given their systemic importance.

What does the NZBA exodus of US and Canadian banks mean?

The sharp decline in the NZBA’s assets certainly reduces its firepower when it comes to accelerating the energy transition. In addition, this blow has in general also a negative impact on the NZBA’s reputation (and perhaps even other climate alliances). It also reignites the discussion around the effectiveness of these climate alliances. For example, while Kacperczyk and Peydró (2022) find that although banks that commit to a science-based path reduce the carbon intensity of their assets, there is little evidence of carbon reductions among affected firms. On the other hand, more recently, Sastry et al. (2024) show that banks that commit to net-zero pathways do not reduce credit supply to polluting sectors, nor do they increase financing for renewables projects.

However, perhaps of more important than this is the fact that the NZBA exodus signals a clear shift in climate sentiment globally. It demonstrates that these large banks are still closely tied to the prevailing political agenda. Ultimately, the banks departure reveal that banks’ climate strategies are largely influenced by governments’ agendas (the “external environment”). Failing to align with this environment can be detrimental to both, banks’ ability to pursue decarbonization strategies and shareholders’ ability to exercise pressure on banks to remain climate friendly. It also reflects how quickly banks can adapt to the environmental landscape of their country, and emphasises the crucial role that government climate agendas play in global decarbonization efforts.

Conclusion

In the end, banks are in a precarious position when it comes to financing the green transition. If banks choose to finance green projects to the extent that they run ahead of broader economic and policy frameworks, they risk investing in initiatives that may not yet be profitable. On the other hand, if banks do not invest in green initiatives, they expose their portfolios to higher climate-related risks. For instance, according to the ECB, “almost all [EU] banks see climate-related and environmental risks as material financial risks” ().

This raises the question of where does a bank’s fiduciary duty (the idea that an institution acts on the best interest of their shareholders) lie. Should it ensure its financial health in the short-term, by pursuing the most profitable investments, or should it ensure that their portfolios are resilient to climate risks, as this is also a crucial step towards its long-term sustainability? This question rolls back to our previous discussion on whether maximizing welfare is the same as maximizing profits, and whether banks shouldn’t be focusing on the former. The recent exit of banks from the NZBA suggests that perhaps the financial system is still leaning towards the latter option – although most banks ensured that they would continue to provide “clients with the advice and capital required to transform business models and reduce carbon intensity” (Morgan Stanley).

All in all, this raises the question of how the banking system can align with a 1.5 degrees pathway when the environment it operates in is not aligned with (or even committed to) it. Against this background, it may not be a big surprise that these banks decided to leave the NZBA.