ESG Strategist - Assessing the energy performance of European covered bonds

Covered bonds are a key funding source for banks, and mostly backed by mortgages. Although covered bonds are considered very safe instruments, they are still exposed to transition risks, given the assets backing them. Therefore, it is important to estimate the energy efficiency of the properties linked to the mortgages backing covered bonds. We use a sample of 22 EU banks and base our calculations on the energy usage of banks’ mortgage loans provided in their Pillar 3 reports. According to our results, DZHyp, Nordea, Intesa Sanpaolo and Erste finance residential properties with the best energy performance within our sample. In contrast, KBC and BPCE seem to register the highest energy usage. Regarding commercial real estate, Erste, Nordea and LBBW report the least energy usage in comparison to their peers, while ING seems to finance very energy-intensive commercial properties. We then calculate the energy performance of the banks’ covered bonds, using the share of residential and commercial real estate loans included in their covered pools. The results indicate that Erste, Nordea and DZHyp covered bonds seem to be the most attractive and safest options in terms of their level of disclosures and associated energy performance. However, some banks still lag behind their peers’ disclosures, such that the estimates they disclose are not representative enough of the entire loan book, hindering the results and possible comparisons.

Introduction

Covered bonds are a key funding tool for banks. By definition, a covered bond is a debt instrument issued by a bank, which is secured by a pool of assets, mostly mortgages. As such, these instruments tend to be perceived as very safe. However, they are still exposed to certain risks, with climate-related risks becoming increasingly important. Indeed, both physical and transition climate risks are some of the risks to consider when investing in a covered bond, given the nature of the assets supporting these instruments.

Unfortunately, there is still little information about the energy performance of covered bonds. A key reason for that regards the fact that most banks are still missing information about the energy performance of the underlying properties securing the mortgages that back covered bonds. That being said, in this publication we aim to address this issue by estimating the average energy performance of several European banks’ total mortgage books, and subsequently, that of their covered bonds.

Sample and methodology

Our sample includes 22 EU banks from Austria, Belgium, France, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain. From these countries, we focus on the banks that have the largest amount of public covered bonds outstanding.

In order to measure the energy performance of mortgages, we rely on banks’ Pillar 3 reports. Since the introduction of Basel III, banks have been publishing Pillar 3 reports, which include qualitative and quantitative disclosures of environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks. For instance, banks have to disclose the energy efficiency of the loans collateralized by immovable property, split by residential and commercial properties. The energy performance of the collateral is divided within different buckets ranging from properties with energy use between 0-100 kWh/m2 to over 500 kWh/m2. The figures in the buckets reflect the gross carrying amount of properties belonging to that specific bucket. However, it is important to note that not all banks report the energy efficiency of all of their collateral. On average, banks report the energy efficiency of 78% of residential properties and 60% of commercial properties.

For each bank in the sample, we consider the disclosures for mortgages with properties located in the EU. We then calculate the weighted average energy performance of both the residential and commercial immovable property loan book, by using the mid-point energy use per bucket (for example, 50 kWh/m2 for the bucket that ranges between 0 and 100 kWh/m2). Below, we plot the results per bank, and the respective share of the mortgage portfolio that the bank provides information on.

Assessing the energy performance of banks’ residential and commercial mortgage books

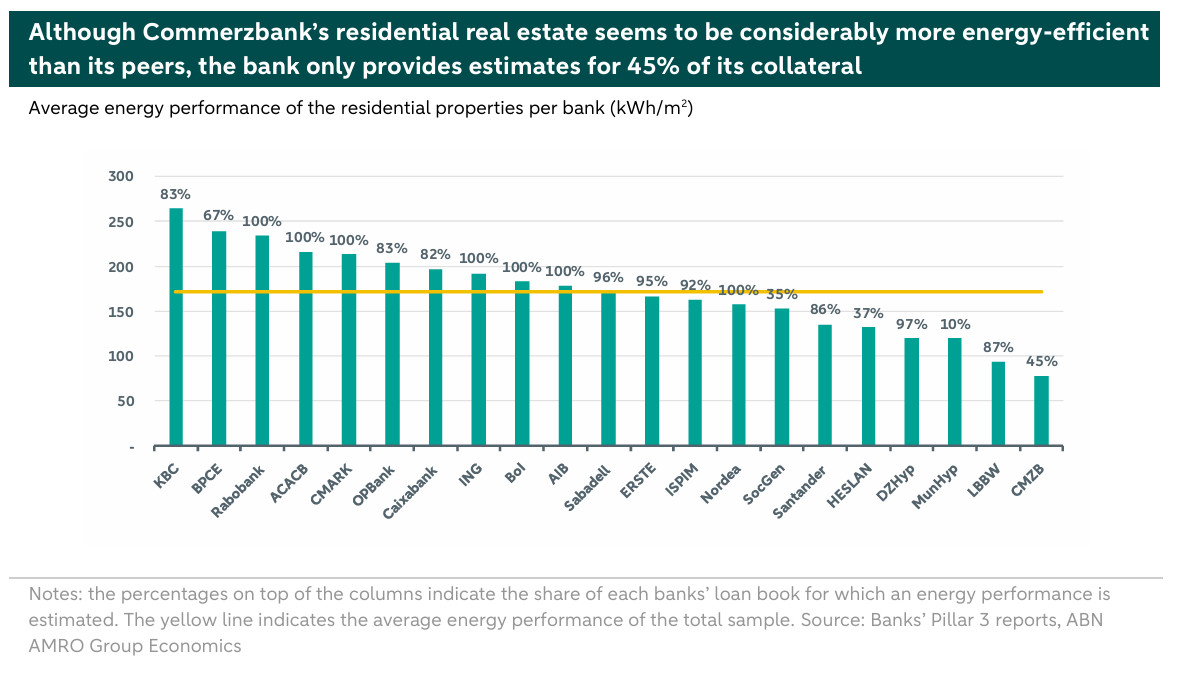

According to the chart below, the energy use of residential properties across Europe averages 171 kWh/m2. From the banks that estimate more than 90% of their loan book’s energy usage, the ones that stand out as energy-efficient are DZHyp, Nordea, Intesa Sanpaolo and Erste, with the mortgage book of DZHyp being the one with the lowest energy usage across this group. These five banks present an average energy usage below the sample’s average energy usage, although considerably above what the European Commission defines as zero-emission buildings (which are, according to the most recent , buildings that require nearly zero or very low amounts of energy) . On the other hand, KBC, BPCE, and Rabobank seem to finance properties with relatively high energy use – and, as such, least energy-efficient – housing stock.

However, some of the numbers presented above do not present an accurate and representative picture of the mortgage book of each bank. For instance, if we take Commerzbank, we can see that its residential energy use is equal to 78.1 Kwh/m2, which is quite low when compared with the sample’s average. However, the German bank only estimates the energy usage of 45% of its residential loan book. The same trend is also observed in other German banks, like MunHyp and Heslan, which only report 10% and 37%, respectively, of their residential loan book’s energy performance. Concurrently, these banks are also the ones registering some of the lowest levels of energy usage within the sample (we explore country-based trends in the following section).

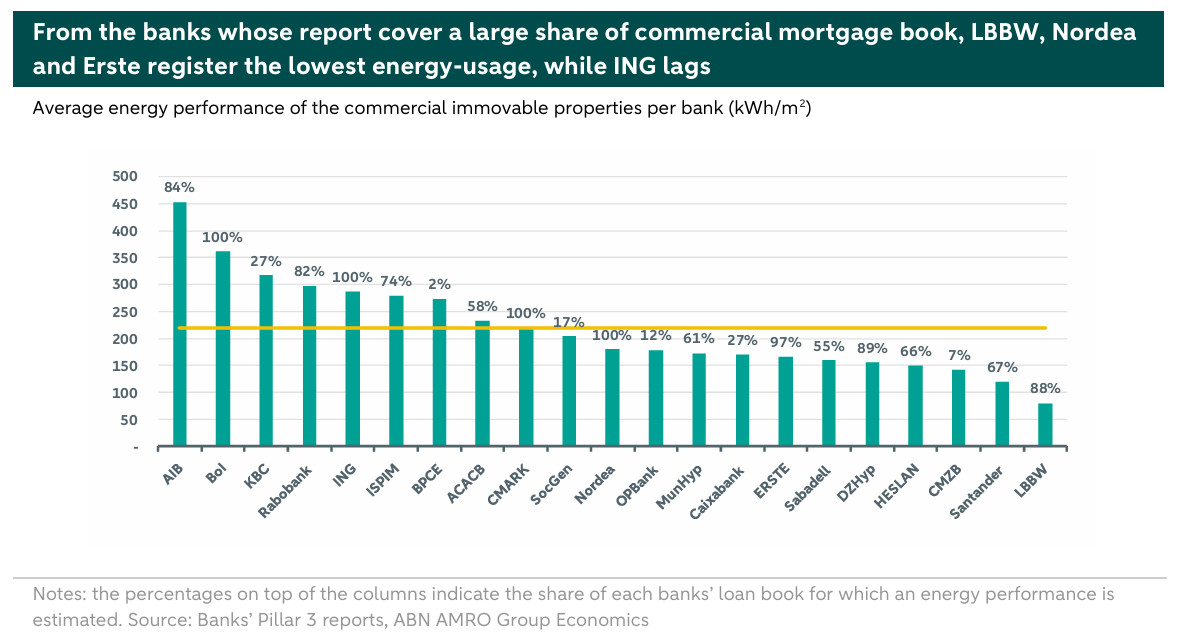

Regarding commercial real estate (see the graph below), banks tend to provide less information about energy usage compared to the disclosures related to residential mortgages. Moreover, in what regards the energy performance of commercial real estate, this tends to also be relatively higher than that of residential properties, currently averaging 218 kWh/m2 across EU banks in our sample.

Some banks, like Commerzbank or OPBank, disclose less than 15% of their commercial real estate’s energy performance. Ultimately, would the disclosure be skewed towards energy efficient mortgages, this could potentially give the impression that the energy performance of these banks’ commercial mortgage portfolios is better than it actually is. As such, the results of these banks need to be interpreted with caution as the picture looks far from complete.

Indeed, the banks that disclose the energy usage of close to 100% of their commercial real estate loan book, seem to have less energy-efficient buildings than the other banks in the sample. For instance, ING’s commercial real estate registers an energy usage of 286 kWh/m2, clearly above the sample’s average. Other banks hold similar results, such as Bank of Ireland (BOI) or Credit Mutuel Arkea (CMARK). On the other hand, despite not disclosing the energy efficiency of its entire commercial real estate portfolio, LBBW seems to mostly finance energy efficient buildings. The German bank discloses the energy performance of 88% of its portfolio, and registers an average energy performance of 79 kWh/m2. Also, Nordea and Erste – which disclose around 100% of their portfolio’s energy performance – register a below-average energy usage of 179 kWh/m2 and 166 kWh/m2, respectively.

Energy performance of covered bonds

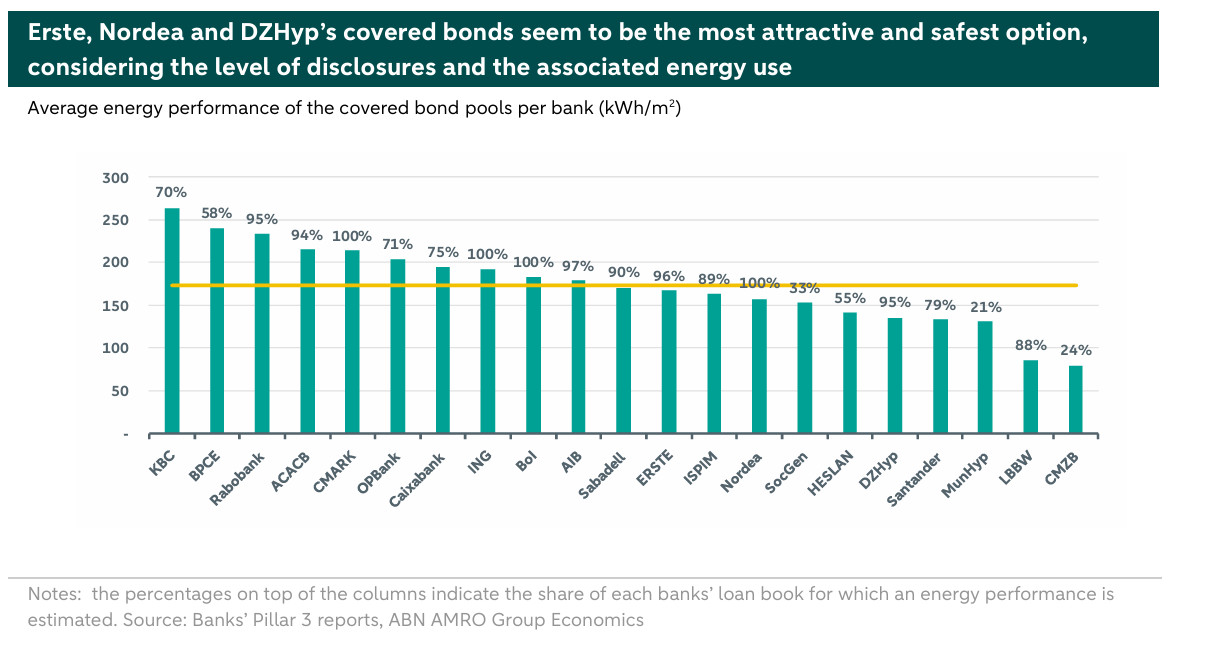

Finally, to calculate the energy performance of the mortgage covered bonds of the banks in our sample, we coupled the information above with that disclosed in their covered bond reports (mostly based in the Harmonised Transparency Template (HTT) and in the transparency reports of vdp members). Banks with a Covered Bond label report in the HTT the share of residential and commercial real estate backing their covered bonds (see ), while German issuers tend to use Pfandbrief transparency reports to do it (see ). Hence, as a final step, we calculate the average energy efficiency of the banks’ loan book weighted by the share of residential and commercial mortgage loans in their covered bond pools. Because most banks have their covered bonds entirely backed by residential real estate, or with a minor share of commercial real estate, the results below closely mimic the previously presented energy performance of the residential real estate mortgage book.

Considering both the level of disclosures (at least above 95%) and the energy performance, there are three banks that stand out: Erste, Nordea and DZHyp. For instance, Erste discloses the energy usage of 97% of the mortgage portfolio linked to its covered pool, and we estimate that the properties in the cover pool have an average energy use of 166 kWh/m2. Nordea estimates the energy usage of 100% of its covered bond mortgage book, and we estimate that its covered bonds have an energy performance of 157 kWh/m2. Finally, DZHyp discloses the energy usage of 97% of its portfolio, and we estimate that its covered bonds display an energy performance of 135 kWh/m2. Hence, the covered bonds of these banks are more attractive and safer options from a transition risk perspective, when considering their energy use and given the relatively high share of mortgages for which energy performance is estimated. The latter should give investors the security that the current energy performance of their mortgage books is skewed towards the properties that are ‘best in class’ in terms of energy usage.

Trends at the country-level

The sample size also allows to identify some trends at a country-level. For instance, German and French banks tend to disclose on average less information about the energy efficiency of their collateral. German banks, for instance, disclose the energy usage of 55% of their collateral, and French banks disclose 76% of it. As we mentioned previously, this is the result of these countries not having enough information – both from their clients and from national databases – about the energy performance of their mortgage portfolio.

For example, French bank Société Générale indicates in their Pillar 3 report (see ) that the collection of data from their clients is currently under review. As such, once finished, this will ultimately allow the bank to refine the numbers disclosed in its publications. Moreover, in the absence of client numbers, the bank has used data from national databases and from other French organizations. In the case of Commerzbank (see ), the bank mentions in their latest report that they have only included non-financial corporations related data, which led to a notable decrease in the portfolio size disclosures compared to previous reporting periods. The German bank expects the extent of their portfolio reporting to increase over time, as it prefers to rely less on estimates provided by external data providers, going forward.

Furthermore, on average, German banks also seem to be the ones with the lowest energy-usage amongst European banks – which might be the result of not having sufficient data that is representative enough of the entire portfolio.

On the other hand, Belgian banks seem to finance the least-energy efficient properties across the sample. In the case of Belgium, we have only considered one bank (KBC), which means we should be careful in drawing strong conclusions about the country as a whole. Nevertheless, KBC’s residential real estate – for which the bank has estimated the energy performance of 83% of its portfolio – displays indeed the highest energy usage of the banks’ sample. This does not come as a surprise, given that in 2020, Belgium registered an average energy intensity of 222 kWh/m2 per year for its entire building stock, according to CRREM, which is considerably above the energy intensity registered by the other countries in our sample. Moreover, the bank mentions in their latest risk report (see ) that real estate is one of the emission-intense sectors in their portfolio that is most exposed to transition risks. They have recently set dedicated ESG monitoring instruments and targets, with a view to decrease their real estate portfolio emissions in the future.

To conclude, while it is important to note that overall these results should not be taken at face value, given that some banks are still lacking quite a lot of information regarding their loan book’s energy efficiency, they can give investors a good indication of which banks that are subject to less exposure to transition risks in their mortgage portfolios. This is not only due to lower energy intense properties being financed, but also due to the fact that better data allows them to more promptly take measures to improve the energy performance of the assets they finance. As such, investors focused on reducing ESG risks on their investments could decide to prioritize covered bonds from banks such as LBBW, Erste or Nordea, which gives them access to a pool of energy-efficient mortgages, while providing security that the data reported accurately reflects the climate risks of the entire mortgage book.