Continued US consumer splurge risks bigger interest rate rises

US consumption growth was unexpectedly strong in March and April, with goods consumption still well above the pre-pandemic normal. Consumers are so far accommodating the hit to their incomes from inflation by using savings from the pandemic, but they are also increasingly taking on more debt. This raises the risk that the Fed has to implement bigger rises in interest rates to bring consumption demand back into balance with supply. Such a move would mean a bigger chance of recession further down the line.

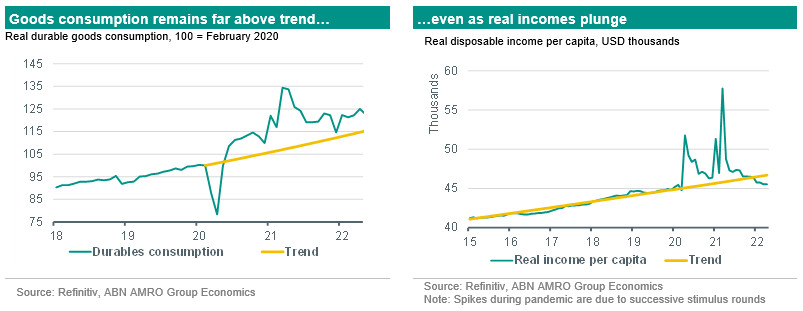

Monthly real personal consumption expenditure (PCE) released last Friday suggested consumers continued to spend like there is no tomorrow in April, while spending in March was also revised higher. Although the advance retail sales report released in mid-May pointed to a volume increase (i.e. adjusted for inflation) of 0.6% m/m in April, the actual outturn was 1.2%. This drove a 0.7% rise in total PCE (including services), which followed an upwardly-revised 0.5% gain in March. The bulk of the rise in PCE was driven by durable goods consumption, which rose 2.3% m/m and is far in excess of trend demand for goods. Services grew at a much more modest 0.5% m/m. This growth mix in consumption is the exact opposite of what is desirable from a growth and inflation perspective at present, given the continued supply side bottlenecks for goods and the shortfall in services demand relative to trend. As a result of the unexpectedly strong consumption growth in March and April, we have significantly raised our annual PCE forecast for the US, to 2.9% in 2022 from 2.3% previously. However, with the supply side continuing to struggle, we expect this to be offset by a greater drag from net exports and reduced inventory accumulation, leaving our GDP forecast unchanged at 2.7%.

Consumers leaning on savings and debt to make up inflation hit

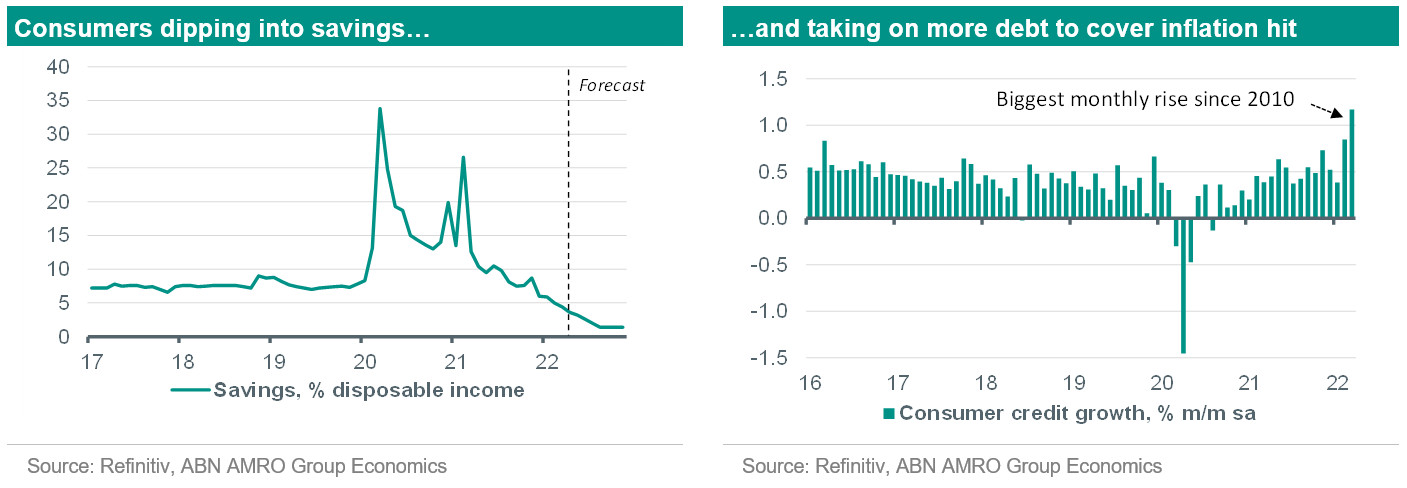

This surge in spending comes against the backdrop of the biggest fall in real incomes for decades due to the surge in inflation. Indeed, the same report last Friday showed that real personal disposable income per capita is now running around 2.5 percentage points below the long-term trend, as wage growth – while somewhat elevated – is running at nowhere near the rate of price growth. Consumers have been dipping into their massive accumulation of excess savings from the pandemic to accommodate this hit, as the savings rate has correspondingly plunged, from a pandemic peak of 33% in April 2020 to just 4.4% in April 2022. This is far below the pre-pandemic trend rate of c.7.6%, and the lowest since August 2008. We expect this fall in the savings rate to continue over the coming months, as consumers further accommodate the inflation hit to real incomes, and our base case assumes the savings rate dips below the all-time low of 2.2% reached in 2005. As well as drawing on the existing stock of savings, consumers have also been relying on more consumer (largely credit card) debt, with the latest data for March showing a jump of 1.2% in outstanding debt on a seasonally adjusted basis – the biggest monthly rise since late 2010. This has come despite the rise in interest rates, which – while having some dampening effect on mortgage applications – has had no such impact on short-term credit.

If consumers don’t rein in spending, the Fed will make them

All of this does not bode well for the outlook for monetary policy. Our base case currently assumes the Fed will raise its policy rate by 50bp at the June and July FOMC meetings, followed by 25bp hikes at subsequent meetings, until the fed funds rate reaches 2.50-2.75% in December. However, despite the downside risks to the growth outlook – particularly later in our forecast horizon – the risks to inflation continue to be upside, while the exuberance evident in the consumption and credit growth data suggests the Fed may have to do more than we currently expect to bring demand back into balance with supply. Indeed, on Monday FOMC board member Christopher Waller signalled as much, when he said he favoured 50bp hikes for ‘several meetings’, and would not take such moves off the table ‘until I see inflation coming down closer to our 2% target’. While one of the more hawkish members of the Committee, we see his view as closer to the current balance of opinion than that of Atlanta Fed president Bostic, who recently floated a September pause in policy tightening given the uncertainty over the outlook. The risk of more aggressive interest rate rises also increases the probability of a recession for the US economy, something we explored in our latest .