Changing our Fed call

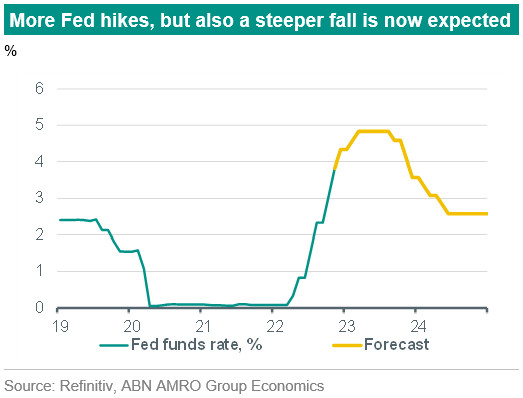

We now expect the Fed to aim for a higher peak in rates, but this is likely to mean even steeper rate cuts later in 2023, once conditions allow.

“The higher you climb, the harder you fall”

Alongside the , we are also adding a further 50bp in rate hikes to our Fed profile. Following the 50bp hike we already expected in December, we now expect two further 25bp hikes at the February and March meetings. This will take the upper bound of the fed funds rate to 5%. However, we still expect significant rate cuts in H2 23, and if anything, the higher peak in rates implies a steeper drop-off, once macro conditions in the US allow for this. We expect cuts to start somewhat later, in September rather than our prior expectation of July, but we also expect 125bp total rate cuts, up from 100bp previously. This will take the form of one 25bp cut in September, followed by two 50bp cuts in November and December. Thereafter, we expect the Fed to downshift to 25bp cuts until rates fall back to the Fed’s neutral estimate of 2.5% by mid-2024. From there we expect the Fed to pause.

Why are we changing our view?

There are two main reasons for our view change. The first is that the labour market is not cooling as quickly as we expected, nor as quickly as the Fed would probably like to see. This was confirmed by last Friday’s October employment report, which showed another solid rise in non-farm payrolls. The decline in job vacancies that we previously highlighted has also seen revisions suggesting less of a softening in labour demand than we thought had occurred. The labour market certainly still looks to have peaked, and data from the household survey suggests employment has essentially been flat for the past six months. However, the pace of cooling is less than expected, meaning that the bulk of the rise in the unemployment rate we expect is now likely to occur somewhat later than we thought previously (we now expect unemployment to peak in mid-2024 as opposed to late 2023). The second main reason for our change concerns the likely timing of a shift in Fed communication. We still think that much of the Fed’s current hawkishness is a strategic attempt to engineer the tight financial conditions the Fed needs right now in order to bring down inflation, rather than reflecting a genuine belief that rates will remain in restrictive territory through to 2025 (as the FOMC’s forecasts currently suggest). However, given the delayed cooling in the labour market, we think the Fed will need to follow through to some extent on current market pricing for rates to rise further in early 2023, with a shift to more dovish communication now more likely to come in Q3 rather than in Q2 as we previously thought.

How can rates fall back again so quickly?

In his press conference , while sounding resolutely hawkish over the near-term outlook for rates, Chair Powell also sent a strong signal that the Fed would move aggressively if it transpired that the central bank had ‘overtightened’. Specifically, he said ‘we could use our tools strongly to support the economy’ if that proved to be the case. Indeed, with the Fed now more likely to overshoot in its rate hikes, we think that falling inflation next year combined with a deteriorating labour market will convince the Committee that rates are too restrictive, and that it will want to recalibrate policy before high rates do more damage to the economy than is necessary to bring inflation back to target. We continue to expect a significantly weaker labour market than the Fed does, with unemployment now expected to peak at over 5% in the course of 2024, whereas the Fed expects unemployment to hold at 4.4%. This pattern of overtightening followed by a course correction also follows previous tightening cycles by central banks, and – assuming our base case of significantly lower inflation combined with a significant weakening in the labour market – we see no reason why the Fed would act differently this time around.