BoE rate hike looks imminent, but Fed and ECB are unlikely to follow

Global Macro: BoE likely the first major central bank to start tightening – In recent days, a number of Bank of England MPC members have made remarks signalling a near-term tightening of monetary policy, which has led to money markets pricing in a full 25bp hike already by the end of this year, and 85bp in hikes by September 2022.

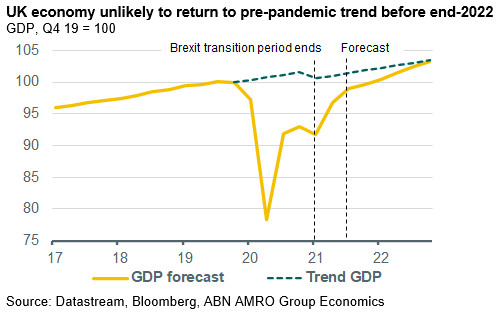

These remarks have come not just from prominent hawks such as Michael Saunders, but also the governor Andrew Bailey, and newly-installed Chief Economist Huw Pill. All have shown concern over the recent run up in inflation, pointing to signs that it may prove to be more than just transitory. As a result of this sudden hawkish turn, we now project the first rate hike from the BoE to come at the 16 December policy meeting (15bp, taking Bank Rate to 0.25%), with this to be followed up by a 25bp hike in the first half of 2022 (taking Bank rate to 0.50%). Thereafter, we expect the MPC to hold fire, with a fall back in inflation, and an economy still performing well below trend, likely to stay the MPC’s hand. There is even the risk that an early tightening by the MPC is in future viewed as a policy mistake, given the transient nature of the majority of the drivers of inflation, and the demand hit we are likely to see from a surge in household energy bills.

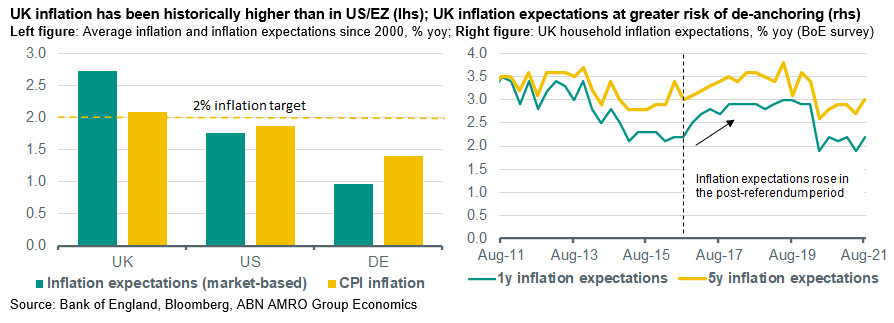

Why is the BoE responding differently to the ECB and the Fed? The hawkish shift at the BoE stands in contrast to the comparatively relaxed postures of the ECB and even the Fed, which are also presiding over elevated inflation. To some extent, this reflects some factors unique to the UK. First, unlike in the eurozone and the US, the UK did not face a shortfall in inflation in the post-financial crisis period; indeed, average inflation since 2000 has been a little above the central bank's 2% target. As a result, household inflation expectations in the UK did not decline; in the post-2016 referendum period, inflation expectations actually increased, as a weaker sterling pushed up the cost of imports. Although inflation expectations have not risen much from the pandemic lows as of the latest August survey, the risk of expectations becoming unanchored is likely to be higher in the UK.

Second, the UK is facing supply shocks not just from imported goods and commodities, but also workers, due in part to Brexit. For instance, the recent, highly public shortage of lorry drivers is at least partly due to the new restrictive immigration regime following Brexit, and these new restrictions have also hampered labour sourcing in the agriculture and hospitality sectors. These factors have constrained potential output in the UK, meaning that the economy runs up against supply-side constraints more quickly than we are seeing elsewhere – with potentially inflationary consequences. Finally, we think another reason why the BoE might be reacting more aggressively is sterling. The post-referendum period illustrated how significant pass-through from currency weakness can be to inflation. It could well be that, by sending hawkish signals and making some early policy tightening steps, the BoE is seeking to engineer a stronger currency to take some of the edge off of the current inflation rise.

Fed and ECB are unlikely to follow this path of early tightening – While we for the Fed, with lift-off now likely to happen in early 2023, we think there will be a high bar for the Fed to row back on its recent communications and to hike before that time. For that, we would likely need to see inflation expectations drifting significantly higher, or inflation re-accelerating – something we do not foresee in our base case. This holds even more so for the ECB. The central bank’s new forward guidance has significantly raised the bar for a rate hike, while it judges that inflation will significantly undershoot its target over the medium term, which is the relevant horizon for monetary policy. Indeed, ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane said recently that the energy price shock was ‘by and large contractionary for the economy’ and that one had to look through energy price shocks. (Bill Diviney & Nick Kounis)