A softer landing – but still a landing

US Macro Update: Moving to a stagnation scenario – Our base case for the US economy no longer foresees a mild recession, but instead a slowdown and a stagnation in output around the turn of the year. The headwinds facing the economy remain very much intact, both from tight monetary policy and the running down of excess savings. As such, we see a slowdown as a question of ‘when’ rather than ‘if’. Even so, we also need to acknowledge the remarkable resilience of the economy over the past year, which points to an underlying strength that we had underestimated. Our updated scenario now reflects this, while also keeping the expectation that the headwinds will eventually have a significant dampening impact on economic activity. Indeed, we judge such an outcome as necessary if inflation is to fall fully and sustainably back to the Fed’s 2% target.

Our new scenario: A slowdown followed by a more gradual recovery

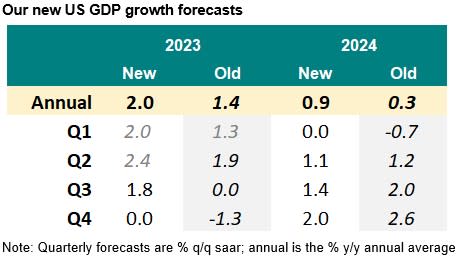

Previously, we expected the economy to contract over Q4-Q1, with a significant rebound in activity in the second half of the year. We keep this profile broadly intact, but we have ‘softened the edges’ so to speak: the growth trough is now more shallow, but also the rebound is less pronounced. Net-net, this still means a significant upgrade to our annual average growth forecast for 2024, which goes to 0.9%, up 0.6pp from our most recent projection of 0.3%. Our forecast for 2023 also rises, to a large extent on the upward revision to Q1 - see table below:

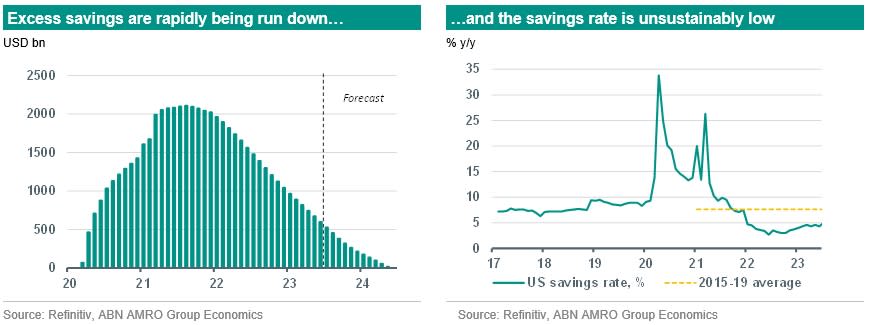

The reasons for the expected slowdown are the same as those that drove our previous, mild recession call. First, while excess savings from the pandemic have been a more persistent support for consumption than expected (and more than was suggested by weak consumer confidence readings), we estimate that liquid excess savings are now very close to being exhausted, and that the savings rate – which is currently well below pre-pandemic levels – inevitably has to normalise, from the current c.4%, back to the 7-8% range.

Rising real wages, helped by falling inflation, will assist with some of this adjustment. But as the labour market continues to cool, we also expect a pullback in consumer spending – particularly on goods, given that goods consumption is still well above the pre-pandemic trend. The US has been a persistent outlier in this regard – in the UK and the eurozone, goods consumption is now well below the pre-pandemic trend. The other key driver of our slowdown expectation is that tight monetary policy – which works famously with a lag – is expected to exert a more meaningful drag on demand in the coming quarters. Monetary policy has already had a significant dampening effect on the most interest rate sensitive parts of the economy – first housing, then manufacturing. This is now evident in the labour market, with manufacturing in particular seeing declines in employment in recent months. The weakening in the labour market will have a knock-on impact on consumption.

What, then, has changed to lead us to revise the scenario?

With the headwinds very much intact, one might reasonably wonder why we would change our scenario at this stage. The primary reason is that it has become clear that there is more underlying strength in the US economy than we previously thought. Alongside the upside surprise to Q2 GDP – which came in at 2.6% q/q annualised, compared to our expectation of a 1.7% expansion – Q1 GDP growth was also revised sharply higher to 2.0%, up from the well below trend 1.3% reading in the third estimate. History has therefore been rewritten, and instead of slowing, the economy has continued to expand at a solid pace – even accelerating in the second quarter. The labour market has also continually surprised to the upside, although it is slowly but surely on a cooling trajectory. Past performance is famously no guarantee for the future, but what the strength of the first half of 2023 does say is that even with the most dramatic monetary tightening cycle in decades, the economy has held up better than anyone could have hoped. This also suggests that, even though the headwinds are likely to become increasingly felt going forward, these headwinds now look less likely to completely throw the economy off course than they did previously. Finally, another key driver of our view change is that amid all of this resilience, disinflation has continued. While wage growth remains somewhat elevated and is still inconsistent with 2% inflation over the medium term, wage growth has also peaked and is on a clear declining trajectory. We continue to think that some rise in unemployment will be necessary to bring wage growth fully back to target-consistent levels, but we no longer think that outright contractions in GDP will be needed to achieve that. Instead, a period of stagnating and below trend growth will likely be sufficient. This means that there is less of a need for the Fed to tighten monetary policy even further, compared to a counterfactual scenario where inflation had stayed more elevated. Still, a stronger economy does raise the risk that inflation takes longer to come back to the Fed’s 2% target than we currently anticipate.

What about tightening credit conditions – do they not still make a recession likely?

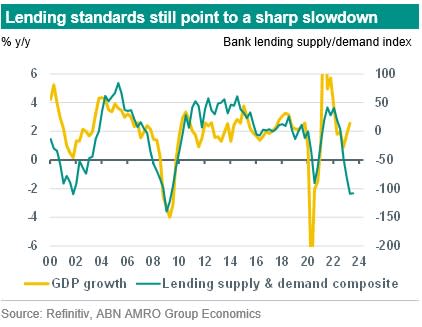

A key driver of our previous recession call was the significant tightening in bank lending standards, which in the past was a very reliable predictor of downturns. The July edition of the Fed’s quarterly (SLOOS) showed a further sharp tightening in lending standards alongside a continued weakening in loan demand, which would support the expectation for a downturn. However, one problem with surveys such as these is that while they are a reliable indicator of the change in lending standards, they say nothing of the level of lending standards. Prior to the current rate hike cycle, lending standards were likely exceptionally loose, reflecting the easy monetary policy of the Fed and the strengthening in household and business balance sheets on the back of generous government support. A tightening in conditions does not therefore mean conditions are now necessarily tight, but rather that they are tighter than before.

To get a better sense for the level of credit conditions, the Fed includes a special set of questions in every July SLOOS survey asking banks how current lending standards compare to the range of standards from 2005-present. With the notable exception of lending for commercial real estate and other nonresidential construction loans, most banks reported that current lending standards were either at the midpoint of the range, or ‘somewhat tighter’ than the midpoint. With worries over the banking sector having receded since the turmoil in March, and with the economy proving to be more resilient than expected in the meantime, we think it is reasonable to assume lending standards hold around these levels for the foreseeable future rather than tighten substantially further. Taken together, this points to less of an impact on bank lending (and therefore economic activity) than the headline SLOOS readings alone would suggest.

What does the more resilient economy mean for the Fed?

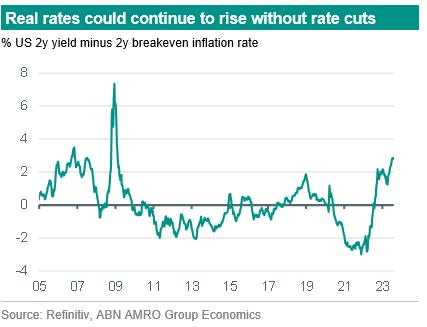

The change in our macro view has limited implications for monetary policy. We expect the Fed to keep rates on hold over the coming half year and to start a modest rate cutting cycle from March onwards. This is for three reasons. First, we continue to expect a significant slowdown to dampen wage growth and in turn inflationary pressure. Second, as mentioned previously, we have seen significant disinflationary progress in recent months, despite the resilience in the economy, and we expect that disinflation to continue assuming the economy does slow over the coming months. Third, Chair Powell and other influential FOMC members such as NY Fed president Williams have made clear that falling inflation by itself would justify rate cuts at some point next year – even without a recession. This is because with nominal rates on hold, real rates would continue to rise as inflation falls. To quote Williams, from an interview last week with the New York Times: "Assuming inflation continues to come down (…), if we don’t cut interest rates at some point next year then real interest rates will go up, and up, and up. And that won’t be consistent with our goals." (Bill Diviney)

What about the eurozone?

In the eurozone, the mild technical recession of Q4 22-Q1 23 has been revised away, leading us to raise our 2023 growth forecast. However, this is a purely backward-looking revision, and in contrast to the US we do not view this as reflecting underlying strength in the economy but instead one-off factors. Looking ahead, we continue to expect a prolonged period of economic sluggishness, with GDP contracting moderately or being close to stagnant during H2 23 and H1 24. With that said, it is possible that volatility in GDP means this does not meet the technical recession definition of two consecutive quarterly contractions. Indeed, activity and survey data published since the start of the summer indicates that there is ongoing weakness ahead. Although GDP growth in 2023Q2 came in higher than expected (at 0.3% qoq) the expansion was not broad-based and was largely due to some temporary factors in individual countries (e.g. Ireland’s GDP jumped 3.3% qoq). Moreover, the details of GDP up to Q1 showed that the eurozone’s domestic economy is much weaker than the changes in total GDP suggest. Indeed, total domestic demand contracted sharply in 2024Q4 and 2023Q1 (-0.6% and -0.7% qoq, respectively), while exports of goods and services stagnated (-0.3% qoq in Q4 and +0.2% in Q1). The relatively benign outcome for total GDP (-0.1% qoq in Q4 and 0.0% in Q1) was only thanks to imports plummeting. The components of 2023Q2 GDP have not yet been published, but our monthly activity tracker suggests that total domestic demand probably continued to contract (barring a one-off jump in intellectual property investment in Ireland) in Q2. The weakness in the domestic economy suggests that it is only a matter of time before the labour market deteriorates and unemployment slowly starts rising, which we expect to happen during 2023H2. The details of the EC consumer sentiment report indicates that confidence in the labour market has deteriorated in recent months. Business surveys by the ECB and EC also indicate that labour shortages have become less severe, particularly in industry. Due to the upward revision of GDP growth in 2023Q1 (to 0.0% from an earlier published -0.1%) and the higher than expected outcome for 2023Q2, we have raised our annual average growth forecast for 2023 to 0.5%, up from 0.2%. However, we have lowered our growth forecast for 2024 slightly, to 0.7% from 0.8%, as we have lowered our forecasts for 2024H1 a touch. These changes do not affect our ECB call, which we updated two weeks ago; see . (Aline Schuiling)