A more rapid cooling in US consumption

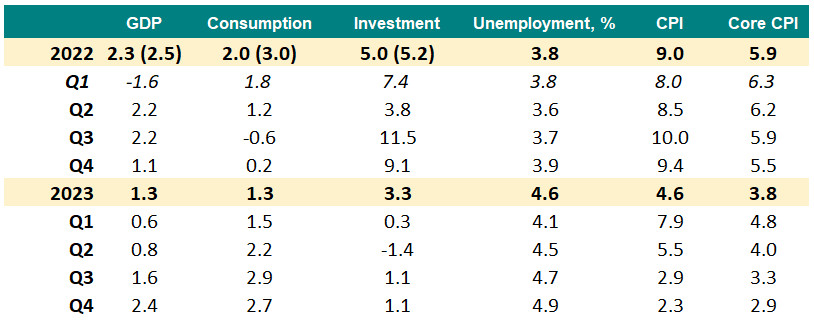

Downward revisions to US consumption data point to much more moderate growth in the first half of 2022 than appeared. This suggests the slowdown we expected is unfolding more quickly than we previously thought, and as such we have downgraded our growth forecast for 2022. However, given the risks around inflation expectations, we still expect the Fed to raise interest rates aggressively over the coming months.

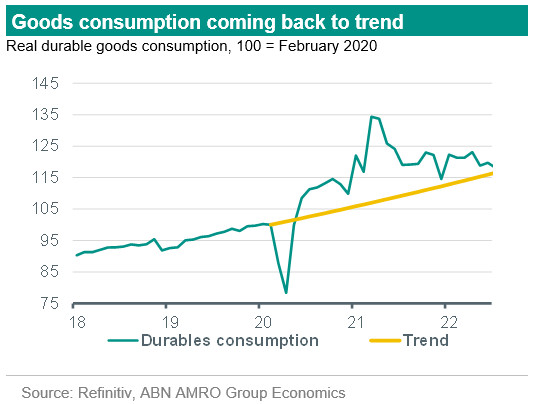

Last week we saw major revisions to US GDP and consumption data. The third estimate for Q1 GDP was largely unchanged on the surface at -1.6% annualised (previously -1.5%), but the details showed an unusually large downward revision to consumption growth (to 1.8% from 3.1%), with this mostly offset by a big upgrade to inventories. This was followed by monthly real private consumption data for May released Thursday, which as well as coming in weaker than suggested by retail sales, also contained a major downward revision to April consumption data (January-March were also downwardly revised, in line with the third estimate for Q1 GDP). Taking all of this together, the picture of consumption in the first half of 2022 has changed dramatically, from one of red-hot demand in the economy to that of much more moderate growth. To be clear, goods consumption remains higher than it would have been absent the pandemic, but the slowdown we expected is happening more quickly than was evident from the data until this week. The downward revisions stand in contrast to the major upward revisions barely a month ago.

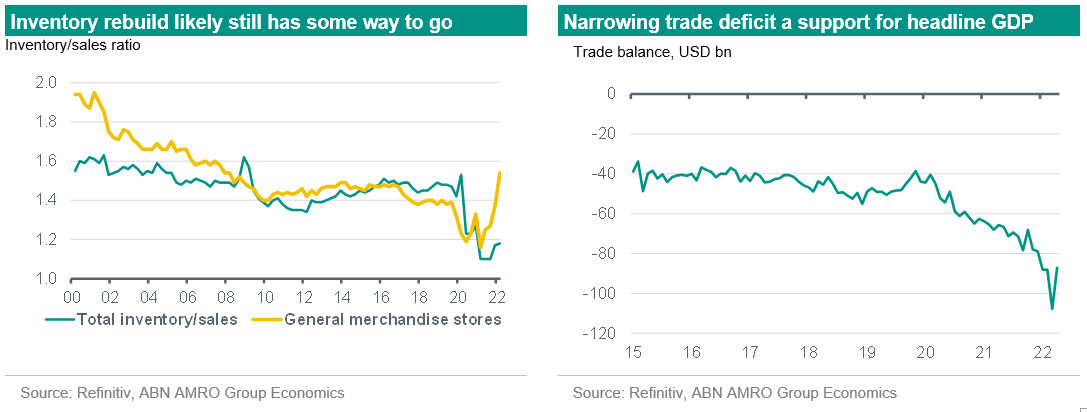

As well as altering how we view the past, the revisions also significantly impact our forecasts, especially for Q2 which we have significantly downgraded. Having previously expected consumption growth of 4.3% annualised in Q2, we now expect growth of just 1.2%. This downgrade is partially offset by an expected bigger positive contribution from net exports, which had been a major drag on GDP in recent quarters. The significant widening in the trade deficit had been largely driven by excess demand for goods in the US, so as this unwinds we expect falls in imports to drive an improvement in the external balance; indeed, we already saw signs of this in the April trade data, and we expect this narrowing in the trade deficit to have continued in May (data will be released next week). All told, we expect headline GDP growth of 2.2% annualised in Q2 – much lower than our previous forecast of 3.8%, but still higher than the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracker (which is currently at -1.0%). Indeed, there is significant uncertainty around Q2 GDP given the volatility in the supply side, and we cannot rule out a negative quarter. This would mean a technical recession in the US. We do not expect this to meet the of recession at this stage given the broader strength in the economy, though the NBER could well call a recession next year once unemployment begins to rise – as we expect – in 2023.

What about the outlook beyond Q2?

With the slowdown in consumption brought forward, we have downgraded our 2022 growth forecast to 2.3% from 2.5% previously, but keep our 2023 forecast unchanged at 1.3%. Both forecasts are below the consensus of 2.5% and 1.9% respectively. We expect consumption growth to grind to a halt in the second half of 2022, as the inflation hit to real incomes and the pass-through from tighter monetary policy depresses demand. However, we expect the supply side to continue to recover, and this is likely to keep headline GDP growth in positive territory. While there are pockets of excess inventory buildouts in response to strong demand (notably in general merchandise retail), the aggregate picture still suggests historically low levels of inventories. We do expect some slowing in inventory accumulation given cooling demand, but there appears still a long way to go before we get back to pre-pandemic inventory levels (see chart above). We also expect positive contributions from net exports, as import demand continues to cool, while investment is also likely to rebound as bottlenecks ease. As we move into 2023, however, we expect the supply side recovery to be largely complete, and investment is likely to see a mild contraction as pent up demand is fulfilled. As such, we expect the low point in GDP growth to be in H1 2023. See below for our full set of forecasts.

Note: GDP and components - annual averages for 2022-23; q/q annualised for quarterly numbers. CPI numbers are annual averages and quarterly y/y averages.

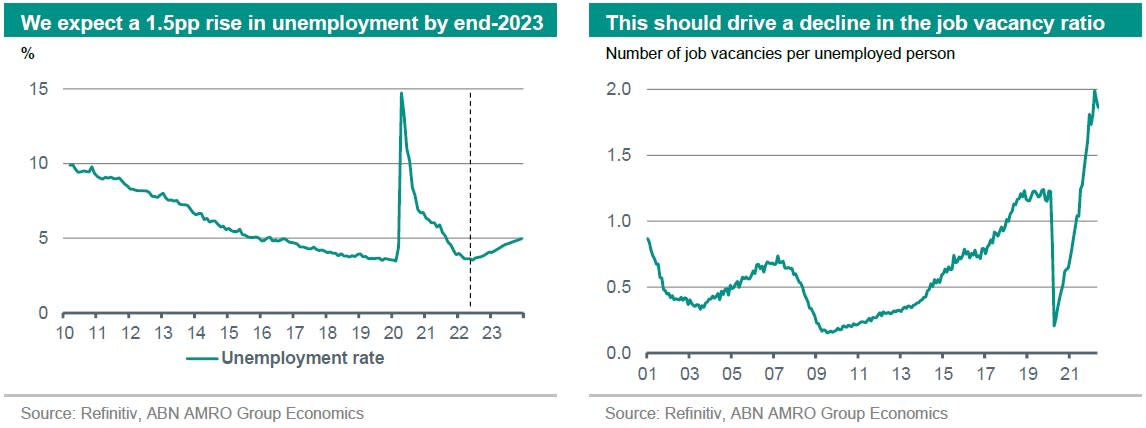

What does this mean for the Fed?

In the near term, not very much. Our base case is for a 75bp hike in July, followed by 50bp hikes in September and November, and 25bp moves in December and February. The more rapid cooling in consumption reduces upside risks to the outlook for interest rates. But given the Committee’s concerns over a potential de-anchoring of inflation expectations – and the sense of urgency evident in Powell’s most recent remarks in Sintra – we do not expect the Fed to rush to declare victory in its inflation fight. The labour market is still exceptionally tight, and there is a long way to go in bringing down excess demand. In our base case, the job vacancy ratio to around half the current 2 vacancies per unemployed person to be consistent with inflation falling back to the Fed’s 2% inflation target over the medium term